Consumers “should question nanotechnology”

Consumer groups and Lausanne University have launched a campaign to raise awareness of nanotechnology – its potential, but also possible risks to health and the environment.

What does sun cream have in common with stain-proof fabrics and a refrigerator that kills odours? All of these were manufactured using nanotechnology with substances invisible to the human eye and that have incredible potential but also pose unknown risks.

Nanoparticles are already found in more than 1,000 over-the-counter products and there are more than 500 Swiss companies which utilise the new technology either in research or production.

However, its widespread use is largely unknown to the Swiss public and has come about without any serious studies on the possible health or environmental impact.

“Over the past 20 years nanotechnology has been presented as revolutionary from a scientific point of view – in the sense that it modifies production processes and allows for advances in electronics, medicine, renewable energy and agriculture,” explained Marc Audétat, science researcher at Lausanne University.

The hopes of researchers are many: there is talk of a gel that will promote the regrowth of teeth, or even the slowing of the effects of ageing.

If these developments remain the stuff of science fiction for the moment, the doubts surrounding the new technology are real. That is why the consumers’ federation in French-speaking Switzerland together with the university’s Science platform have jointly launched a campaign to raise awareness among the public, and to stimulate debate on the pros and cons of nanotech.

Part of the campaign is an exhibition that opened this autumn and will travel across the country next year.

Natural or manmade

Nanoparticles are either present in nature or manufactured and consist of a few million atoms. It’s their number that determines their properties.

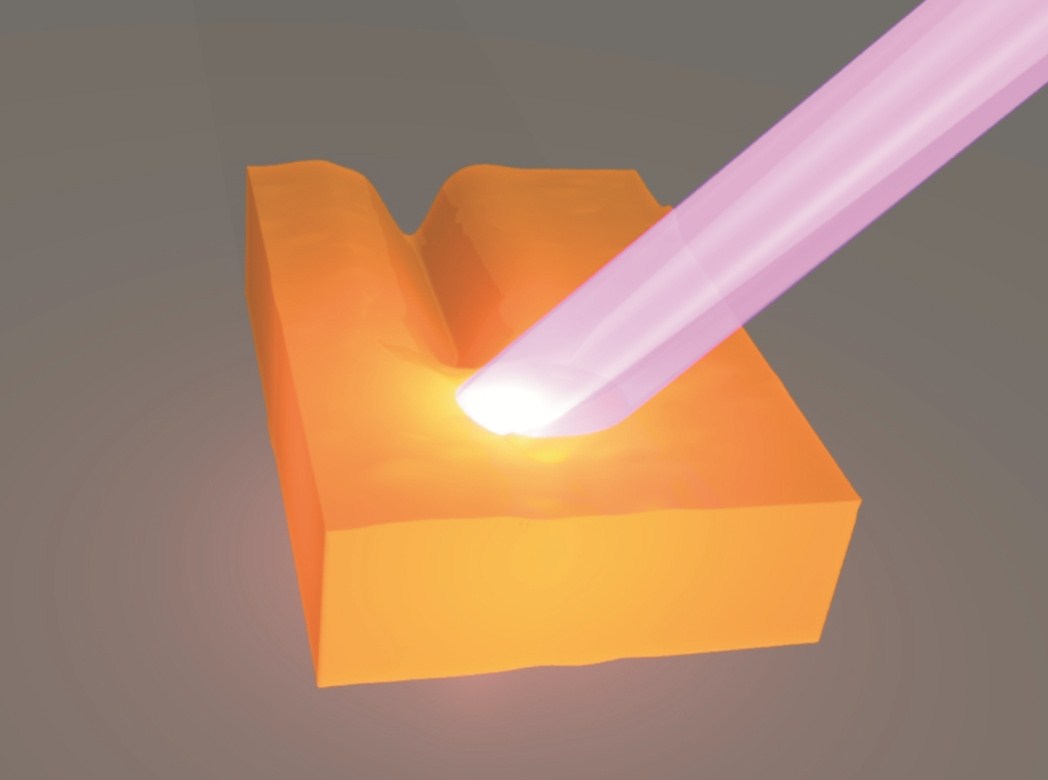

“Some materials if reduced to infinitely small dimensions change character. That’s the case with titanium dioxide which in its natural state is used as a pigment in paint in the form of a white powder but if reduced to a nanoparticle becomes transparent and becomes an ultra-violet filter,” said Huma Khamis, biologist and nanotechnology expert for the consumers’ group.

Their properties can be surprising but also extremely difficult to define because it is enough to alter just one atom to cause radical modifications.

In addition, nanoparticles have a particularly large contact surface with respect to their mass and are therefore very sensitive to the external environment and highly unpredictable.

Cause for concern is human contact with these substances.

“We can’t rule out that these particles find their way into the organism, through food or are breathed in, with health consequences,” Khamis said.

Tumours in mice

According to a study by the National Science Foundation, in comparison to the research into possible applications of nanotechnology, the amount of resources Switzerland invests in the potential risks is extremely low.

Some experiments on animals have shown that there are negative effects on the respiratory tract. Or, in the case of titanium dioxide (used in sun creams), mice have developed tumours.

At the moment however, toxicological research is in the embryonic stage and it is therefore difficult to introduce norms for commercial applications – whether in Switzerland or abroad.

“This does not mean that consumers should be used as guinea pigs,” said Khamis.

“It’s up to industry to prove that these substances placed on the market are truly harmless, especially cosmetics or any product that comes into contact with the skin. It’s not only the public which has a right to know which items contain nanoparticles. It’s a question of transparency and free choice.”

The use of nanoparticles has also raised some concern regarding the impact on workers. Asbestos – which continues to kill 100,000 people each year in the world – is often taken as an example, although the comparison may seem exaggerated at first glance.

Carbon nanotubes are particularly suspect. Last year, 700 tons of the substance were produced. Cylindrical molecules, nanotubes have extraordinary thermal conductivity and mechanical and electrical properties making them valuable in applications for a diverse range of structural materials.

But if these qualities are more than promising for industry, the health effects seem all too similar to those of asbestos.

“History has taught us how important it is to conduct preliminary research to determine the possible effects of new technologies to avoid what happened with asbestos,” Audétat says.

More research needed

Audétat says that the risk of a cover-up today is less than it was when asbestos cases began to surface. He is concerned that instead of transparent debate, the accent has been placed on scientific progress.

A few years ago, the Swiss occupational health insurer, Suva, published recommendations for companies using nanotechnology. No law on the subject has been passed, but the government did issue an action plan in 2008 on synthetic nano materials directed at both industry and retail companies to facilitate the identification of possible risks.

“These kinds of initiatives are important but they don’t go far enough. Switzerland must invest in research into the impacts of nanoparticles on health in a way that regulations can be developed for industrial applications, agriculture and food,” concluded Khamis.

“Despite the efforts, the scientific community has not yet reached a consensus on the definition of a nanoparticle or the precautions when modifying it.”

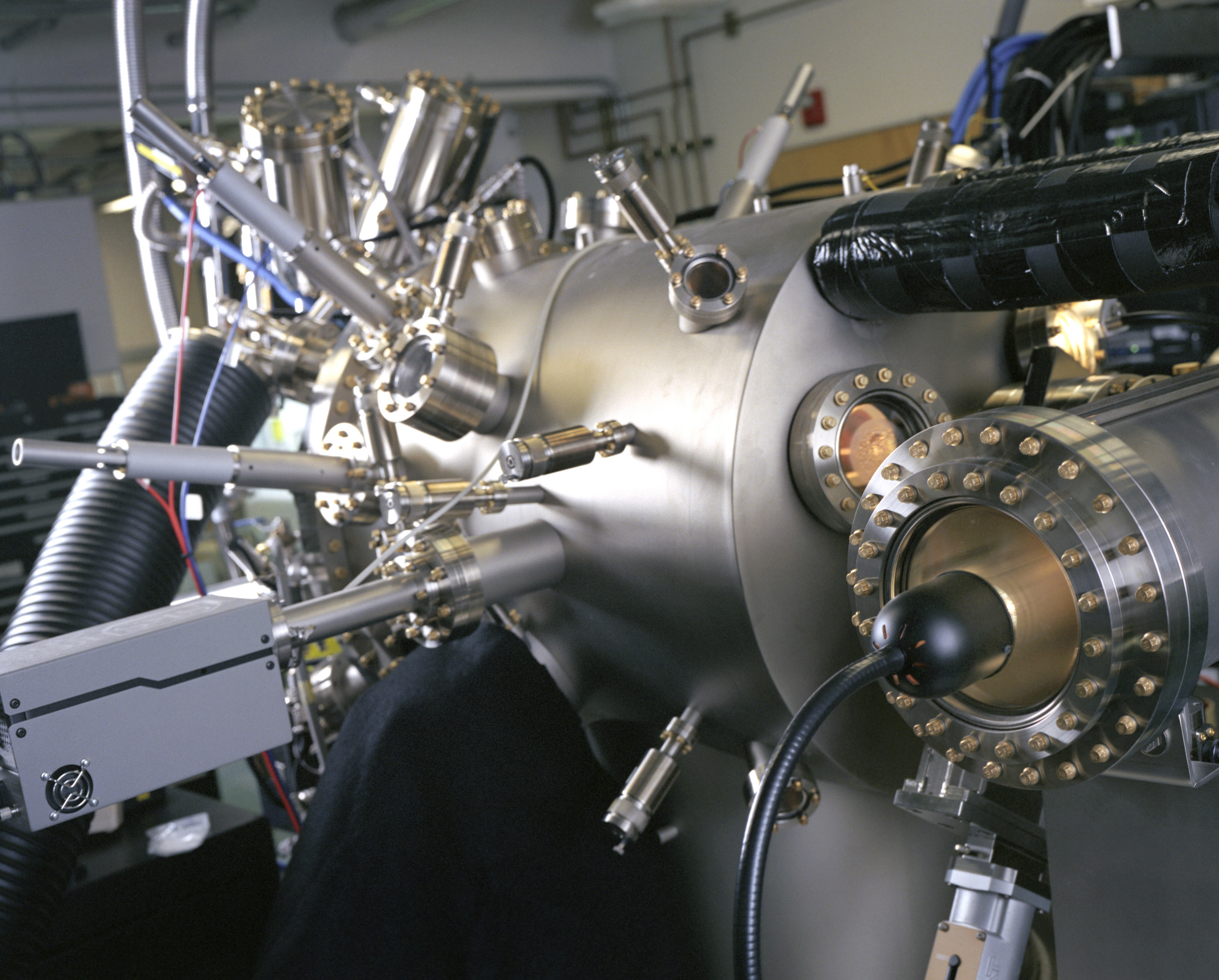

Nanotechnology is the study of manipulating matter on an atomic and molecular scale. Generally, nanotechnology deals with developing materials, devices, or other structures possessing at least one dimension sized from one to 100 nanometres. Quantum mechanical effects are important at this quantum-realm scale.

Nanotechnology is very diverse, ranging from extensions of conventional device physics to completely new approaches based upon molecular self-assembly, from developing new materials with dimensions on the nanoscale to investigating whether we can directly control matter on the atomic scale.

Nanotechnology entails the application of fields of science as diverse as surface science, organic chemistry, molecular biology and semiconductor physics.

According to a study completed at the Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (Assessing the Swiss Nanotechnology Landscape) 140 institutes, companies and private individuals have patented 350 inventions based on nanotechnology.

Leading the way are patents (22%) for chemical products, followed by the pharmaceutical industry (20%), measurement tools (17%), electronic components (17%), medical applications (6%), automation systems and computers (3%).

The consumers’ federation in French-speaking Switzerland together with the Science platform at Lausanne University are behind a new exhibition called “Nanotechnology: products, promises, preoccupations”.

The exhibition will tour Switzerland next year.

February: Fribourg

March: Neuchâtel

April: Jura

May: Geneva

June: Sion

Autumn: Ticino

The show will be accompanied by a series of debates with experts from the world of science.

(Translated from Italian by Dale Bechtel)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.