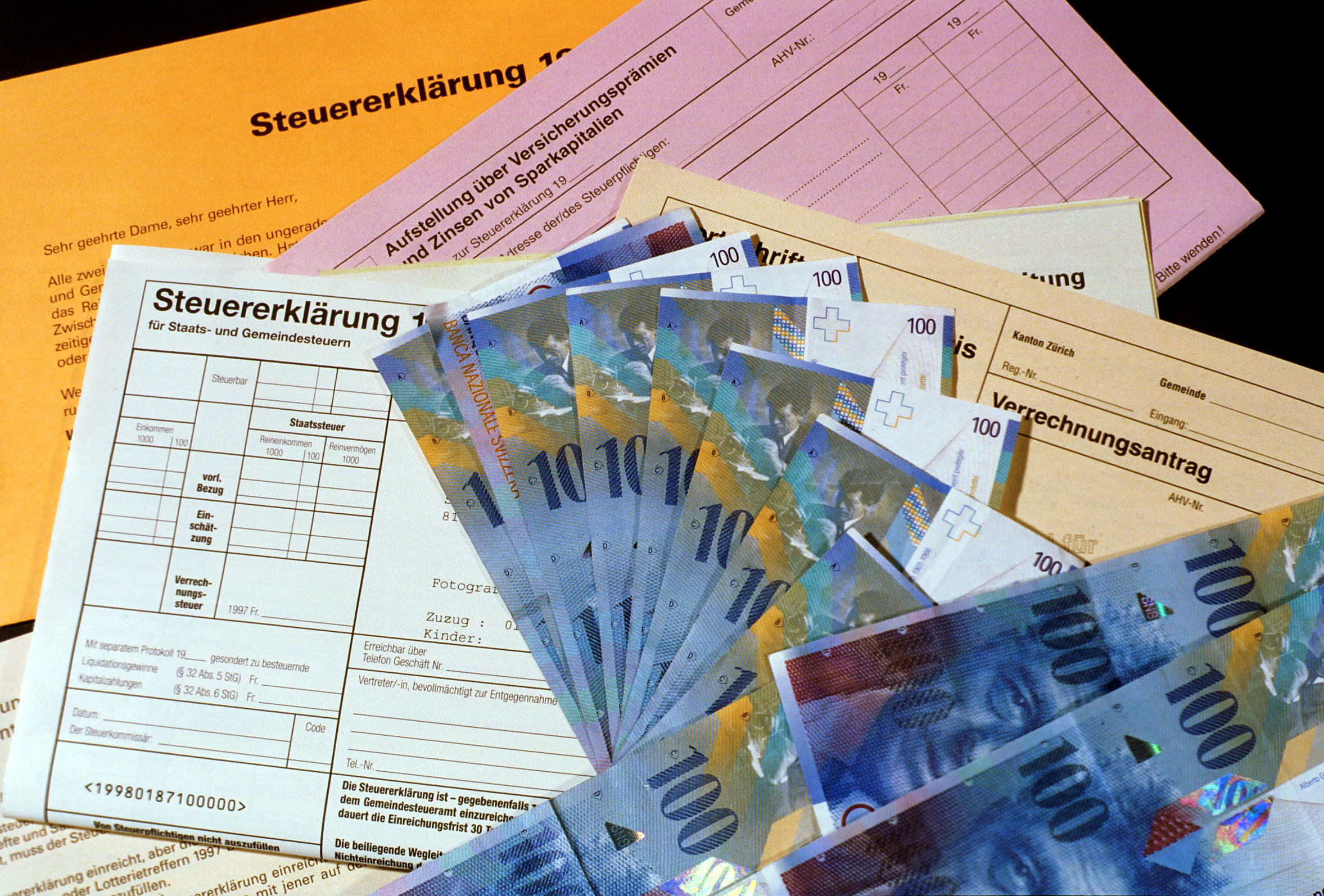

Tax evasion isn’t just for foreign bank clients

The Swiss are usually considered honest when it comes to paying their taxes, but as in other countries, tax avoidance costs the public purse a pretty penny. Just how much is actually lost is difficult to estimate, however.

The local authorities in Egerkingen, canton Solothurn, have just revealed the names of six people who have avoided paying their taxes for years despite have sufficient income – a decision that could have legal consequences due to Switzerland’s data protection legislation.

If anything, this situation clearly shows that the Swiss aren’t as honest as they would like to think they are.

Amnesty programmes

To get their hands on money that has been stashed away, the authorities at all levels in recent years have offered a number of tax amnesties to convince fraudsters – or those who had ‘forgotten’ to declare income – to come clean.

The federal government gave a partial amnesty in 2010 to allow people to file tax forms for undeclared sums without being fined. They were asked to pay up to ten years’ worth of back taxes, however, and three years if the assets came from an inheritance.

Slightly more than 3,900 people took advantage of the once-in-a-lifetime offer last year, allowing the authorities to recover CHF174 million ($183 million) in federal taxes. In 2011, CHF250 million was recovered, and CHF213 million the year before.

The French-speaking canton Jura in northwestern Switzerland decided to go even further. Taxpayers who did not declare up to CHF51,000 face no fines or back taxes, while more significant sums are taxed based on a flat rate.

The Jura government believes that the amnesty, which runs until the end of 2014, should identify CHF300 million in hidden assets and increase tax revenues by CHF3 million for the canton and CHF2 million for the communes.

What is collected as part of these amnesty programmes probably represents only a small share of all hidden assets. But no one really knows exactly how much remains hidden from view. Federal and cantonal tax authorities contacted by swissinfo.ch say there are no reliable estimates.

More

Paying taxes is not just about money

A politician’s proposal

Centre-left Social Democrat parliamentarian Margret Kiener Nellen, a former president of the House of Representatives finance commission, was unable to get an estimate. Her solution was to crunch the numbers herself.

She used one the few studies done on tax evasion, published in 2006 by the economics professors Lars Feld and Bruno Frey. They reckoned 23.5 per cent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product was not declared in tax filings.

Kiener Nellen took this number and applied it to the average household income, estimating that tax evasion cost CHF18 billion every year.

“I think I was very conservative with my estimate,” she told swissinfo.ch. “Of course my work was criticised. Some economists say tax evasion is only half that of my figure, but even so, it’s still a huge amount.”

The fog surrounding tax evasion numbers looks set to stay. The house rejected a proposal by Kiener Nellen to collect statistics on tax fraud. If it had been accepted, the cantons would have had access to some bank data in cases of tax fraud or if someone had forgotten to declare assets.

All honest?

In a recent poll carried out for the SRF television programme ECO, 95 per cent of those who answered said they had never hidden anything from the taxman.

Nils Soguel, a professor of public finance at the Swiss Graduate School of Public Administration, is sceptical, however.

“You are never totally honest when you answer this type of question,” he said, “even if everything is supposed to be anonymous.”

Kiener Nellen is less surprised by the result. “Most people simply don’t have the means to cheat,” she pointed out. “Their income is on their salary certificate, so they can hardly hide anything.”

“Fraud usually involves the self-employed and high-income earners. As a lawyer, I’ve seen legal setups such as trusts and foundations to move funds to offshore locations such as the Bahamas.”

For individuals filing tax returns, there are different ways of defrauding the authorities: hiding bank account details or other assets, not declaring revenue, and making illicit claims on expenses.

For employees this is somewhat difficult, as their annual income is recorded on the so-called salary certificate that employers provide for tax purposes. In some cantons, the certificate is sent directly to the tax authorities. For employees, fraud can only concern any revenue made on the side and not from their main job.

The self-employed are more problematic. Kiener Nellen gives the example of dentists who agree to charge patients 20 per cent less if they pay in cash. In such cases, revenue is not declared and value-added tax is not paid.

It is also possible to cheat by increasing the value of deductibles for items such as travel and meals.

Trusting tax authorities

The authorities normally assume that most of the country’s inhabitants are honest and declare everything. They don’t go hunting for fraudsters. “We only carry out random checks and run the ruler over someone’s tax return only if there are good reasons to believe there is fraud going on,” said François Froidevaux, head of the Jura tax service.

“The tax authorities aren’t particularly nitpicking,” confirmed Soguel. “They are forced to act if they are notified, but otherwise they are fairly tolerant. And with online tax filing, some services don’t even ask for supporting documents.”

This could all change, though. If banking secrecy is abolished for foreign bank clients, it could also be the case for Swiss customers. Switzerland’s cantonal finance ministers would like to have the same access to bank account data currently being negotiated with the United States.

The government said recently it is considering moving in this direction. This is not necessarily the best option according to Soguel.

“It would send a bad message,” he said. “It would be like saying the Swiss have something to hide. Instead of trusting people, we would be considering their motives as suspicious.”

Banking secrecy could eventually disappear for Swiss bank clients.

The government has submitted draft legislation for consultation that would unify the country’s criminal fiscal legislation. Cantons would be allowed to request bank client data in cases of tax evasion (non-declaration of assets) and not just of tax fraud. Access would only be granted if there were a strong indication of wrongdoing and as part of a penal investigation, however.

Parties on the Right have responded by launching an initiative banning the automatic exchange of data concerning clients living in Switzerland. It would allow data transmission for criminal investigations, but under more restrictive conditions. They have until early December to collect the 100,000 signatures required to force a nationwide vote.

(Adapted from French by Scott Capper)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.