The hidden truths of the Gurlitt collection

In the interest of transparency, Bern’s Museum of Fine Art has published a first list of artworks contained in the controversial Gurlitt collection, which gives an unexpected picture of what it really contains, says art journalist Michèle Laird.

For those who were expecting the identification of a thousand hidden masterpieces worth more than a billion dollars, the belated publication of the listExternal link may be a disappointment.

Works by Rembrandt, Renoir, Chagall, Picasso, Monet and Toulouse-Lautrec are in the inventory, but many are on paper. Lithographs, woodcuts and posters are also in great numbers.

On the other hand, the list is deeply revealing of the motives and operational skills of Hildebrand Gurlitt, the Nazi art dealer whose collection was held secretly by his reclusive son Cornelius until it was accidentally discovered in 2012. Cornelius Gurlitt died in May, naming the Bern Museum sole heir to the collection in his will.

By attempting to complete the provenance checks before releasing the information, the German authorities may ironically have stalled important research on the project and contributed to amplifying its value.

Because the list has been communicated as a PDF instead of being posted into a provenance database, there will be a number of surprises once it has been properly studied.

One such surprise is the very large number of works by German Expressionist and Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) painters, considered “degenerate” by the Third Reich. It is unlikely that they were purchased individually, leading to the question of whether Gurlitt acted alone.

Munich and Salzburg lists

Upon publication of the list, swissinfo.ch immediately contacted the museum to obtain a clarification on the warning foreword that specifies “Kunstmuseum Bern cannot be held liable for the completeness of the lists”.

The list appears in two parts: the works of art discovered in the Munich apartment of Cornelius Gurlitt was compiled by the German Task Force. The Bern museum’s spokesperson, Ruth Gilgen, admitted that the inventory was little more than a starting point for further provenance research, now that Bern has committed itself.

Asked whether the Munich list was complete, she referred the question to the communications director of the German Task Force.

Matthias Henkel said the question required a complicated answer, so he responded with statistics instead. The Munich trove, he said, contained 1,278 pieces, including 34 works of art added after the initial raid (but excluding art found later in Gurlitt’s home in Salzburg).

In January 2014, 499 works of art, identified as potentially looted, were published on the German Lost ArtExternal link database.

“The collection comes in three packages,” Henkel added. First, 499 works (see above). Second, 477 works qualified as “degenerate art”, the modern art that Hitler abhorred and wanted eliminated from Germany. However, Henkel specified that 230 of those pieces had been bought from museums before 1933 and “cannot therefore be considered looted art”. Third, the rest belongs to the Gurlitt family.

Henkel added that the presence of numerous prints and lithographs in the collection complicates matters, since sources rarely specify the edition number, which makes it virtually impossible to determine from which museum it was purchased/obtained/confiscated in the first place.

He did not mention the possibility that the art was acquired directly from the artists under duress.

In February 2014, two years after the discovery of the Munich hoard (and only three months after its public disclosure in November 2013), additional works of art were found in Cornelius Gurlitt’s Austrian residence.

The list of this second trove was compiled by the Swiss museum, but it too lacks the information that could be useful to potential claimants. Like the Munich list, it contains no provenance information and is not alphabetical.

Family man

But lying below the surface of the two lists are three portraits of the same man.

Many works in the collection are Gurlitt family heirlooms. An astonishing 150 paintings were made by Hildebrand’s Danish-German great-grandfather, Heinrich Louis Theodor Gurlitt.

Books were amassed by various members of the family (see box) and the collection also includes 120 artworks made by Cornelia GurlittExternal link, Hildebrand’s sister, who committed suicide in 1919 at the age of 29. With these family artefacts, a fifth of the collection is already accounted for.

Envoy for Hitler

Together, the Munich and Salzburg troves reveal the obsession of a man vested by a singular mission. Hitler, a mediocre artist himself, wanted to create the museum of all museums in his hometown of Linz, and Hildebrand took it upon himself to help deliver the goods.

Few names are missing from the roll call of European art history starting with Dürer and Cranach in the 15th century and climbing all the way up to Rembrandt, Delacroix and Fragonard in the 17th and 18th centuries.

It is difficult to determine yet whether the innumerable works of art from the end of the 19th century by Rodin, Manet, Monet, Renoir, Maillol and Pissarro were also meant for Hitler’s museum, which was never built. They may already have been too modern for the Führer.

It is worth noting, however, that although the roll call is impressive, the works from most of these artists will probably be considered minor.

Unexpected delights

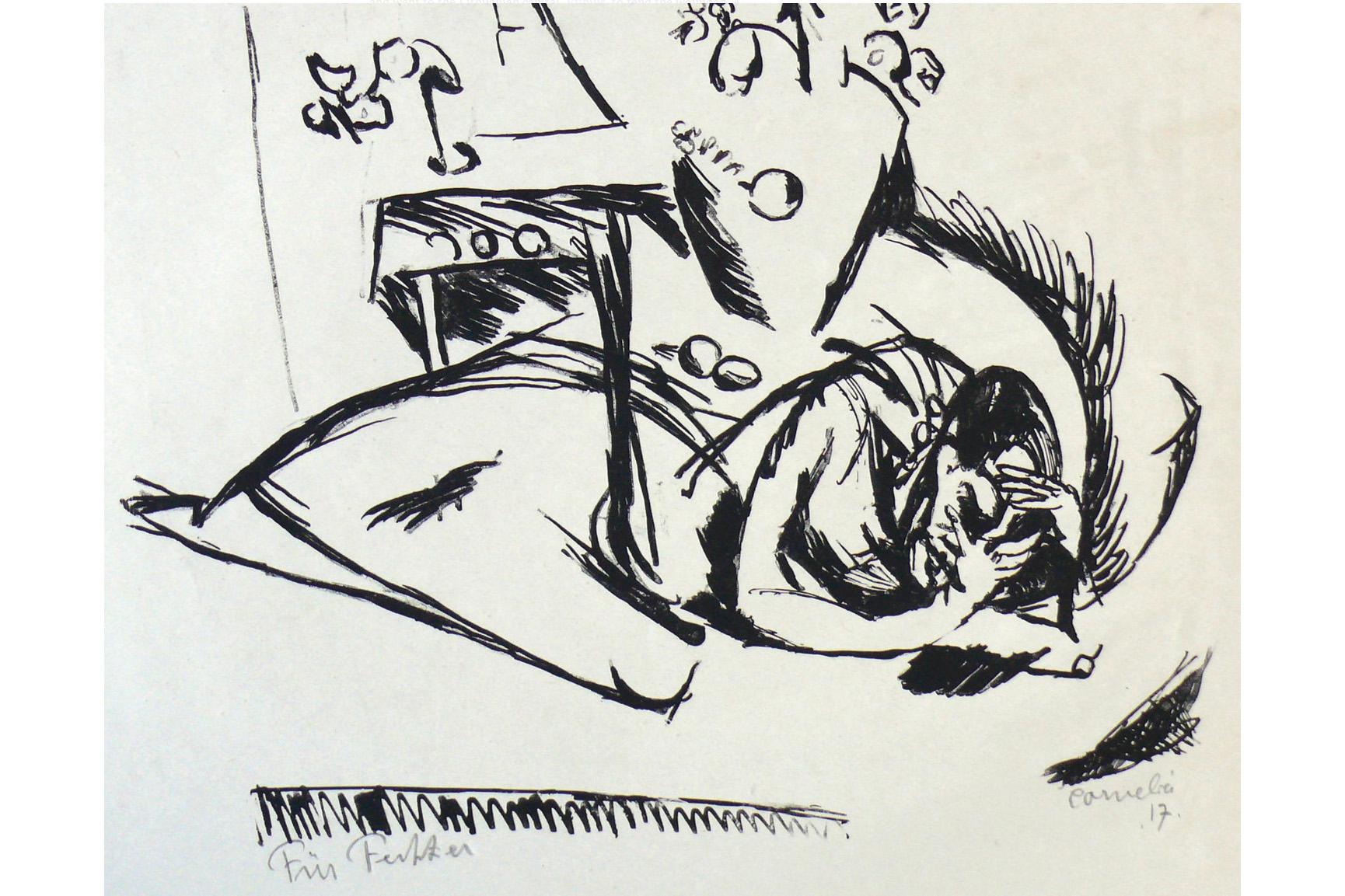

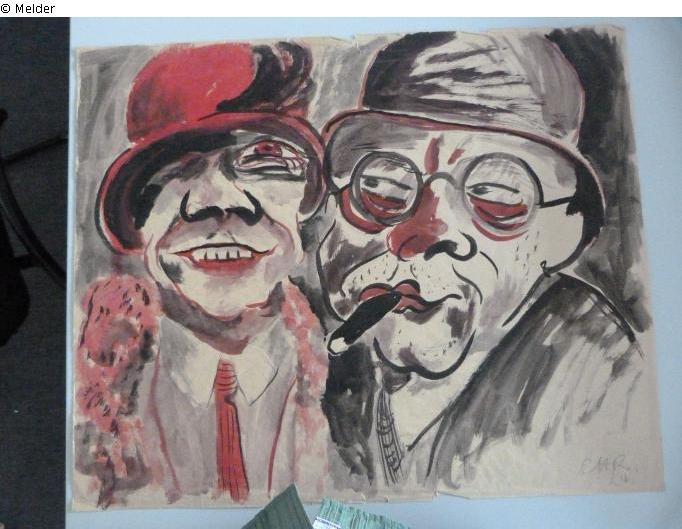

What is more troubling in the Gurlitt collection is the list of 20th century “degenerate artists”, whose lives were destroyed by Hitler’s appraisal. Many had to flee Germany to save their lives and Gurlitt had only to swoop down to collect their art.

There are suspiciously large numbers of works by Georg Grosz (more than 30), who fled to the US in 1933, Karl Schmidt-Rotluff (more than 25, including some lovely aquarelles) who was expelled from the painters’ guild and forbidden to paint by the Nazis, Erich Heckel (more than 40) whose entire production was confiscated from German museums and whose woodcut blocks and print plates were destroyed. Even the pro-Nazi Emil Nolde (more than 34) became persona non grata to the regime.

Among the unexpected delights of the Gurlitt trove are the rediscovery of artists like Heinrich Campendonk (more than 28), who fled to Amsterdam, Rolf Grossman (more than 84), who disappeared during the Second World War, and the belated recognition of Max Liebermann (more than 60) whose Two Riders on the Beach will likely be restituted in the coming days.

Provenance research has yet to determine the conditions under which the art was obtained, but the fact that Gurlitt concealed its existence after the war would indicate that he acted out of self interest, not to save the doomed art.

The research is a tall order for the Bern museum, but a challenge that it appears to welcome. It has been reported that an anonymous donation of CHF1 million ($1.04 million) has been made to help it with this task.

Gurlitt family

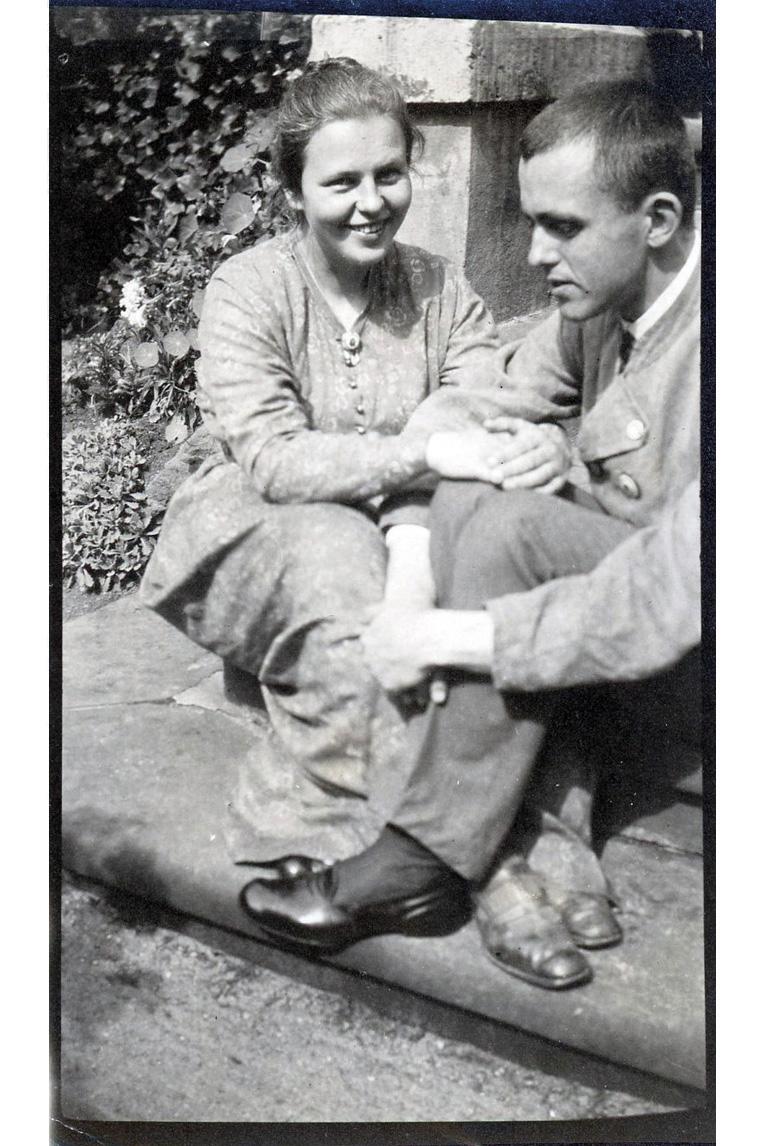

Cornelius Gurlitt was born in Hamburg on December 28, 1932, to Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895-1956), one of four official art dealers for the Nazis, and Helene Gurlitt, a dancer.

Hildebrand’s sister, Cornelia (1890-1919) was an artist.

Cornelius’s grandfather, also called Cornelius (1850-1938), was an architect and art historian

His great-grandfather, Heinrich Louis Theodor Gurlitt (1812-1897), known as Louis, was a Danish-German landscape painter whose brother, yet another Cornelius (1820-1901), was a composer.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.