Using music to help premature infants

Friederike Haslbeck sings to babies. But not to all babies. As a music therapist she helps premature infants and their parents relax and bond. As a researcher she’s investigating whether music helps develop a premature baby’s brain.

The neonatal intensive care unit at Bern’s university hospital is open and airy. Sunlight shines into the room from above. Nurses sit in a row at the entrance, overseeing a room full of incubators and keeping track of physiological data on numerous screens in front of them. Here and there, parents sit beside the high-tech cribs holding their tiny children.

Is the term used to describe how far along a pregnancy is. A normal pregnancy can range from 38 to 42 weeks. Babies born prematurely, after as little as 24 weeks in the womb, are treated in a neonatal intensive care unit.

Techniques like in vitro fertilization have increased the number of multiple births and babies born early. But the technology used to treat premature infants has also developed, so that today, even babies born more than three months before their due date (in the 24th week of gestation) have a chance of survival.

Friederike Haslbeck works with premature infants in both Bern and Zurich, treating six to eight premature infants per day. Music therapy generally begins one to two weeks after the babies are born.

Music therapy

“The most important instrument is the human voice,” says Haslbeck. “And when I work only with a premature infant – at the incubator or warming bed – then I only use my voice. What we know from early studies is that actually babies prefer the human voice over instruments.”

Haslbeck often works with parents and babies together, using music in combination with a therapy called ‘kangarooing’.

“Then I prefer to bring a monochord with me to accompany the singing. It’s a very special instrument. It has a lot of vibration and only one sound.”

More

Haslbeck humming and playing the monochord

During kangarooing, a mother or father lies in a reclining chair with the tiny baby on their bare chest, skin-to-skin. Haslbeck places the monochord against the parent’s elbow, so that the vibration passes through both parent and child.

“This is something that is missing for a premature baby. Because when we think about what it would actually hear if it were still in the womb, it would be deep sounds. From digestion. From the circulation of the blood. The deep heartbeat.”

Studies have shown that music can help a premature baby stabilise physiologically, says Haslbeck. Often, she sees the effects of the music therapy on the baby’s monitor. The heart rate slows down and the amount of oxygen in the blood goes up, which are good things. The baby breathes more deeply and regularly. “So that it’s not fast, and slow, and a break. It’s more in a rhythm.”

Haslbeck also sees other signs in the babies. Movements under the eyelids when the eyes are closed, raising of the eyebrows, smiling, putting their tongues out, starting to suck. “Or they do ‘o’ and ‘aah’ with the mouth. These are all signs of feeling comfortable.”

More

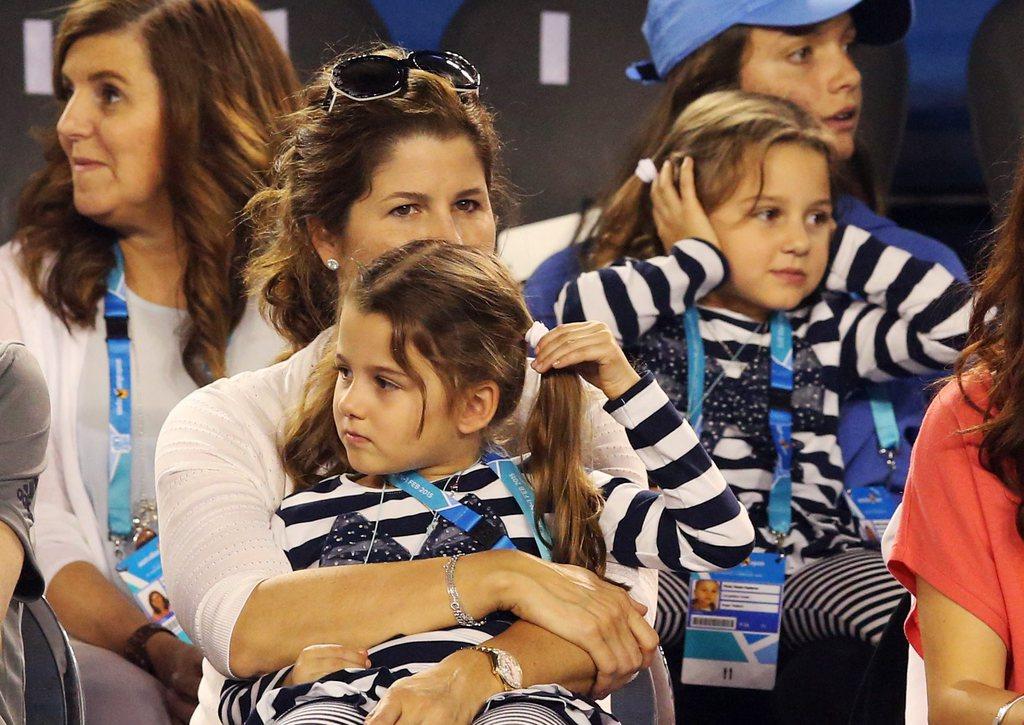

Bonding with a premature baby

Reducing stress

Noise, worry and uncertainty all contribute to stress in the neonatal intensive care unit. “So if I want to support the bonding process between child and mother or child and father, the first thing I have to do is relax the parents and to relax the infant,” says Haslbeck.

This functions very well with the monochord. “You don’t have to say to the parents, ‘Keep calm’. You don’t have to make breathing exercises with them. You can just play it, and it happens.”

Besides not knowing with any certainty what will happen to their newborn child, parents have to deal with what Haslbeck describes as a “huge lack of privacy and intimacy”.

That’s definitely a problem, say new parents Anna and Remco, whose son Casper was born in Bern in October, two months ahead of schedule, weighing 1,600 grams.

More

Learning to be a couple while caring for a sick child

“There was just this little space around his incubator and the curtain, and then you want to kangaroo but it’s such a small space,” says Anna. “You just don’t have any private moments with your child.”

Remco agrees. “You have a curtain that you can close, but there’s no auditory privacy. You hear everything. Everybody hears you.”

In one sense, this was an advantage for the couple. Although their son didn’t have music therapy, they were able to hear Friederike Haslbeck working with other children.

“The whole room was filled with this magic music,” remembers Anna. “What a difference the music makes, even in this clinical atmosphere. It’s as if you’re swimming in a cold pool and then you go into a warm one. And you say, ‘Wow, I didn’t realize that I was in this cold pool the whole time!’”

The beginnings

The first studies evaluating the effect of music therapy on premature infants were conducted in the 1970s. Their goal was to test whether music could be harmful. In the 1990s, one of the pioneers in the US, Jayne Standley, started to train music therapists for work with infants.

As of 2013, there were six hospitals in German-speaking Switzerland providing music therapy for premature babies, but none in French-speaking regions, where it is less accepted.

Matthias Nelle, Director of the Division of Neonatology at the Bern University Children’s Hospital, says that for several years the hospital has been using an approach that integrates all the senses in the care of premature infants. “We offer massage, we offer olfactory stimuli, we pay special attention to light and colours.” Music therapy was added “to address the sense of hearing individually in our small children,” he says.

Meanwhile, at the Zurich University Hospital Haslbeck is the project leader of a research study evaluating whether music therapy with premature infants has an impact on their brain development. Using magnetic resonance imaging, the researchers are comparing the brain development of babies with and without music therapy, at 40 weeks of gestational age.

“Our hypothesis is that the babies who receive music will have bigger volume, better function, more connections,” she says.

Sixty premature infants will be enrolled and evaluated from 2016 to 2017. The study will last five years. “We have no results yet, but what we know is that music is one of the very rare things in the world that stimulates a lot of important areas in the brain at the same time,” says Haslbeck.

Ultimately, helping families is the focus of Haslbeck’s work.

“It’s not only about the music,” says Haslbeck. The objective is “to soothe a baby. To interact. We are social beings. We are not computers.”

You can contact the author via Twitter @JeannieWurz

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.