Living in the valley of the shadow of death

The residents of the Lötschental in canton Valais know not only how beautiful snow is, but also how dangerous.

The land register for the picturesque valley, which is surrounded by 3,000-metre mountains, records no fewer than 73 avalanche “hot spots” – overhangs that are often the starting point for large avalanches.

Indeed locals say there are in fact only two avalanches: one on the left side of the valley and one on the right.

Every winter several avalanches are seen. “If you live here, that’s normal,” Elmar Ebener, who lives with his family in the village of Blatten, told swissinfo.ch. “Avalanches are part of nature. We live here with danger and with nature.”

With its four villages and few hamlets, the 27km valley has a total of only 1,500 inhabitants.

But even if the locals are used to avalanches, one event remains in the collective memory: the winter of 1951. Snow had fallen heavily everywhere across the Alps that year – and avalanches were numerous: 165 people were swept away in Switzerland, 93 died.

Six people perished in the hamlet of Eisten, which belongs to the commune of Blatten. Three of them were children.

“That has left its mark on the people here,” said Ebener, who only knows about the event from hearsay. “People, especially older ones, don’t like talking about it.”

Cut off

Since then no one in the Lötschental has died in an avalanche. The avalanche barriers have been continually rebuilt and improved and have proved their worth in two extreme winters.

The winter of 1999 entered the record books as a “winter of the century”, with some 1,000 avalanches crashing down Switzerland’s mountains.

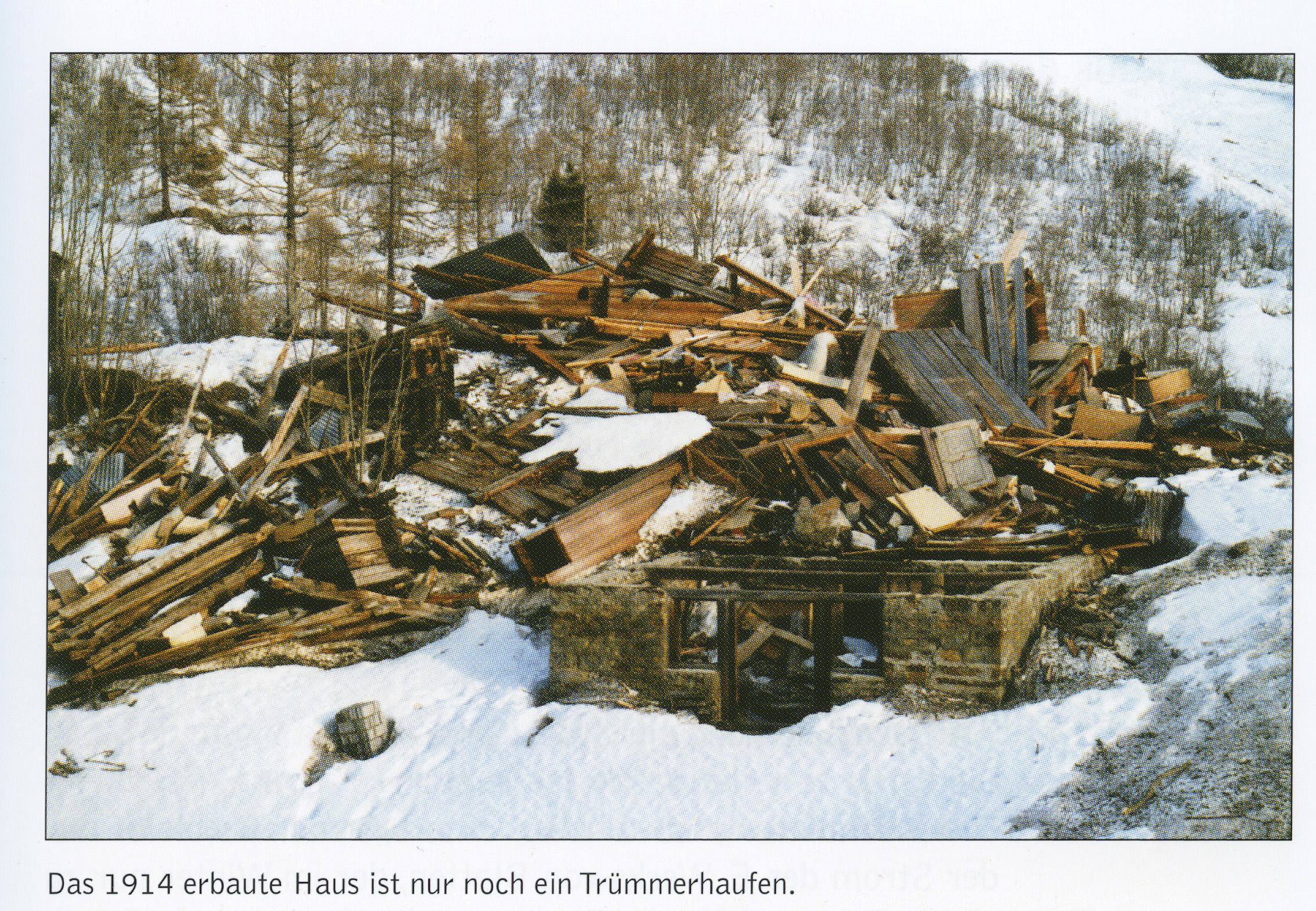

Lötschental also witnessed countless avalanches. Although no one was killed, the damage was considerable, according to Ebener. The road was covered and impassable; buildings were damaged and some were destroyed; protective trees were brought down and cultivated land was damaged.”

Because the one street that goes through the valley was filled with snow, the entire Lötschental was cut off from the outside world.

“Every winter we’re cut off for one or two days,” Ebener said. “But in 1999 it was ten days – pretty exceptional.”

Airlifts

The road was shut on February 18, 1999, and the first people were evacuated from the danger zone a day later. The airlifts began two days later.

“Tourists and people with health problems were flown out in a helicopter, locals and food were flown in,” he said.

“An avalanche had damaged a power pole so in Blatten we didn’t have any electricity for four days. But thanks to our own small generator we could at least have power for a few hours.”

Ebener said that since he was still studying at the time, he had to be flown out. “For me it was worse to watch the whole thing from outside and not to know what was going on. It was easier in the valley.”

Danger map

Lukas Kalbermatten, mayor of Blatten, told swissinfo.ch that one can say which areas are at risk fairly accurately with the use of avalanche maps.

“So for example there are red zones, where no houses can be built because the avalanche danger is particularly high. In blue zones construction is permitted but under certain conditions. In the white zone there’s no danger,” he said.

“After 1999 our map had to be changed in only two places,” he added, explaining that this showed how accurate it was.

But despite the danger map, the path of an avalanche is never totally predictable. Some come dangerously close to dwellings. “An avalanche missed that house by a hair,” said Ebener, pointing to a house on the edge of a small village.

But it’s not only buildings that can have lucky escapes, says Monica Albisser-Anker, who has been coming to Lötschental for more than 30 years.

“In the winter of 1999 the priest left his house to go to church. Just outside his house he realised he’d forgotten his rosary. He turned back to go and get them, and at that very moment an avalanche roared past him and his house.”

Divine intervention? The victims of 1951 weren’t so lucky.

Sandra Grizelj in Lötschental, swissinfo.ch (Adapted from German by Thomas Stephens)

According to the Swiss Federal Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research, an average of 25 people die annually from avalanches.

12 people died in an avalanche at Evolène in Valais in 1999.

Seven people were killed in an incident in the Bernese Oberland on Janaury 3, 2010.

Avalanches killed 17 people in Feburary 1999 in Switzerland.

About 1,000 avalanches caused material damage of more than SFr300 million.

More than five metres of snow fell in the Alps in early winter.

The danger of avalanches was increased by strong gales which resulted in an unfavourable stratification of the snow layers.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.