Scotland vote: a true victory for people power

The citizens of Scotland have decided against full independence: 55% versus 45% in favour. But in doing so they have called for more democratic powers for all citizens. In a fascinating process, which could become a model for other sovereignty referendums, Scotland's conversation on people power can now inspire the rest of the world, writes Bruno Kaufmann, editor-in-chief at people2power.infoExternal link.

The sheer numbers are impressive. Out of an electorate of 4,285,323 registered voters, 84.6% participated in the historic popular vote on September 18. This is the highest voter turnout in a UK popular vote since 1945.

“The atmosphere was brilliant,” said one 16-year old student from Aberdeen after visiting a local polling station for what was probably the most important decision in her life. “Wow, I have a say in this country.”

In the final tally a total of 3,623,344 votes were cast: 1,617,989 voted yes (44.7%) and 2,001,926 said no (55.3%).

Having a say on such an important issue and being part of a public conversation is a feeling most Scottish citizens seem most proud about in this referendum process.

Both the ‘Yes’ and the ‘No’ campaigns made it very clear in the final days before the vote: people in Scotland and across the UK and Europe need more democratic powers, not less.

In a last-minute attempt to swing the vote towards the union, even the ”three amigos” from London – David Cameron (Conservative Party), Ed Miliband (Labour Party) and Nick Clegg (Liberal Party) – travelled to Edinburgh to underline this point.

Clearly the official campaigns on both sides sometimes gave their own exaggerated spins to the debate. Some tried to undermine the broad public discussions around challenges linked to national security, the welfare state, what currency an independent Scotland should have, and how the issue of European Union membership should be dealt with.

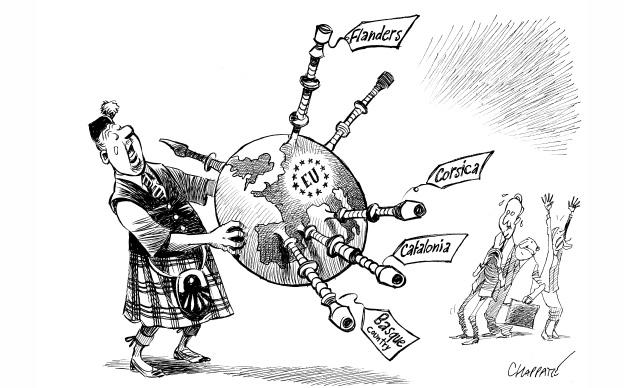

This was also reflected in statements by many foreign observers and commentators, possibly in the hope of transforming the Scottish referendum into a blueprint for their own cases for or against greater autonomy and independence. Even Russian politicians tried to instrumentalize the vote for their own ambitions in Crimea, and Brussels leaders warned against a ‘Balkanisation of Europe’.

Bruno Kaufmann

Bruno Kaufmann serves as Chairman of the Democracy Council and Election CommissionExternal link in Falun, Sweden; and is president of the Initiative and Referendum Institute Europe and co-chair of the Global Forum on Modern Direct DemocracyExternal link. He is the correspondent for Northern Europe at the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation and Editor-in-Chief of people2power.infoExternal link, a direct democracy platform created and hosted by www.swissinfo.ch.

What many of those campaigners and observers missed, however, is the actual referendum process that took place. The democratic maturity on display was extraordinary and a model for a true popular vote. Three aspects are especially interesting: the extent of public involvement, the overall agreement, and the conduct of the electoral process.

Never before in modern UK history have so many citizens taken part in so many public debates and demonstrations in such a long process. People understood that this referendum was not about giving their vote away to someone else, but about strengthening it for themselves.

“I have voted in every election since I was 18 but I have never felt like this,” an elderly man confessed after voting in Kirkwall, Orkney. Obviously citizens were able to differentiate between such a huge decision and the traditional choices between different stakeholders in a typical election.

The so-called Edinburgh Agreement between the Scottish and the UK government – signed on October 15, 2012 – prepared the way for the popular vote process. One weakness of sovereignty referendums in the UK and in other parts of the world is that they are not provided for in a written constitution and cannot be triggered by a citizens´ initiative.

However, the UK and Scotland overcame these limitations by agreeing on the right to vote and other cornerstones of a referendum. This again is a major difference to many similar attempts across Europe to organize sovereignty referendums, such as in Catalonia or the Italian Veneto region. As long as you have no agreement on a referendum process with the entity you wish to leave, it will be more difficult to organise a free and fair popular vote.

The conduct of the ‘#Indyref’ – as the Scottish independence referendum was known on social media – provides a model for how to organize and conduct such a democratic decision. This includes broad public information campaigns, strict transparency requirements and the setting up of a comprehensive infrastructure for participation in debates and actual voting.

For several weeks before voting day it was possible to vote by post, and on September 18 no less than 5,579 polling stations were open for 14 hours across Scotland. It was not only these elements put in place for the public that made the opinion-making process such an informative and empowering one, but also the efforts of many media organizations, including citizen-driven ones such as bellacaledonia.org.ukExternal link.

Despite the despair of losing, after having experienced some of these positive aspects during the public debate, many ‘Yes’ supporters remain upbeat.

“This is just the beginning, not the end,” said one Yes-supporter on Friday morning after hearing the result. “The people of Scotland have won.”

But this ‘victory’ is just one step, as many challenges and problems lie ahead, and there are no guarantees the promises made by London will be kept, especially if a Conservative/UKIP coalition takes over in the UK next year after the general elections.

Furthermore, unlike in Switzerland, there is no formal constitutional process available to the people of Scotland to restart the whole process.

And indeed, more change will (have to) come. After September 18 active citizenship and participative democracy will play a more important role than ever before, not only in Scotland, but in other parts of the UK, Europe and in the rest of the world.

Even if some voices and forces abandon their promises of more democratic powers to the citizens, they will have learned something: Scotland’s referendum process is much more than a yes or no to independence; it is the expression of a new political culture – a true victory for people power.

Opinion series

swissinfo.ch publishes op-ed articles by contributors writing on a wide range of topics – Swiss issues or those that impact Switzerland. Over time, the selection of articles will present a diversity of opinions designed to enrich the debate on the issues discussed.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.