“No surprise” that Haiti literally collapsed

Maybe some of the buildings in Port-au-Prince wouldn’t have buckled in last week’s earthquake had the roofs been better attached to the walls.

In Haiti and across the developing world, population growth and urban migration have led to a proliferation of new buildings, many as resilient to natural disaster as a house of cards.

The 7.0-magnitude quake last week is estimated to have killed around 200,000 people across Haiti. An aftershock on Wednesday measuring 6.1 sent frightened survivors running into the streets.

“These buildings are in no way designed for earthquake loadings and other severe natural events,” said Michael Havbro Faber, a professor of risk and safety at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH).

The problem is also a logistical one, Faber believes. “These cities are developing at a rate where the local authorities have no chance to enforce any building code.”

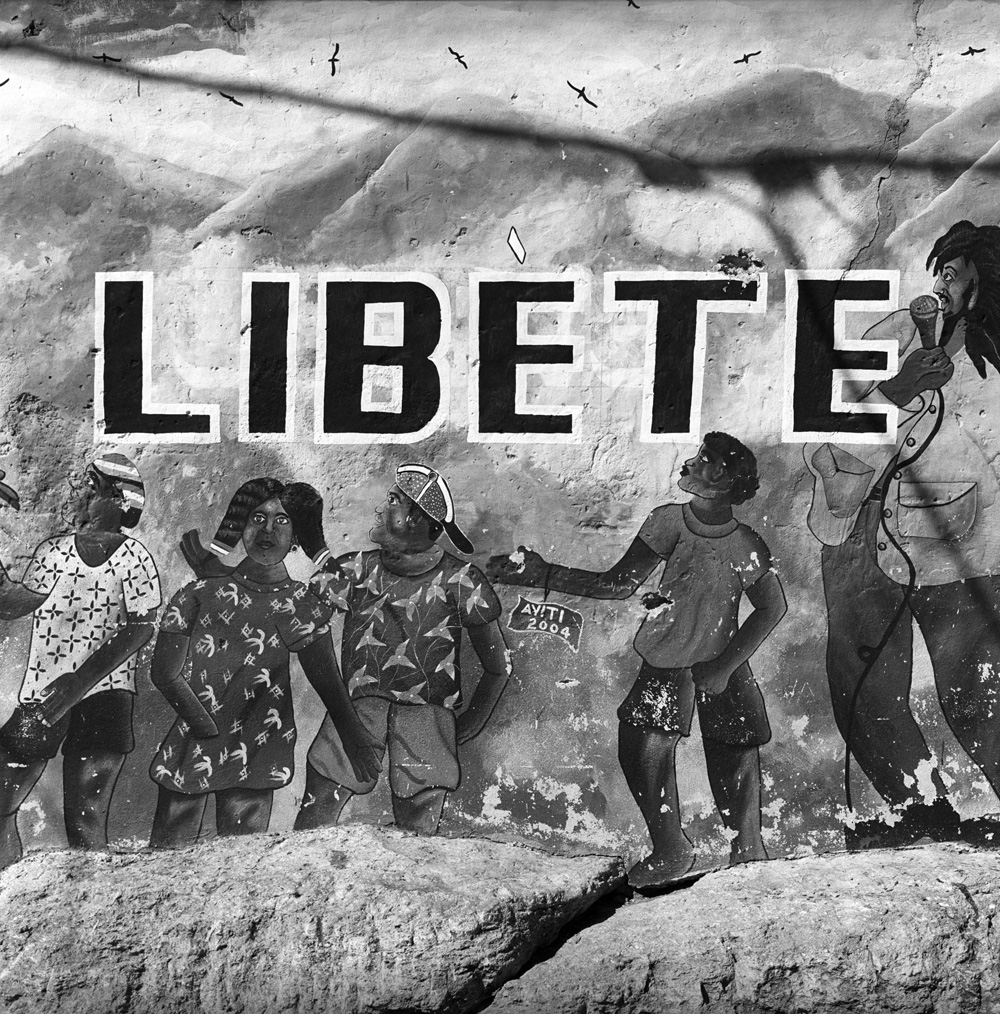

Experts agree that Haiti’s shoddy construction and lack of building standards exacerbate disasters that would ordinarily be considerably less destructive. In 2004, a storm that barely registered as a hurricane killed more than 3,000 people and left 250,000 people homeless in the city of Gonaïves.

But problems with construction are usually highlighted only when something goes wrong. “These are small beams of reality, which we get to see whenever earthquakes take place in these regions,” Faber told swissinfo.ch.

A moderate quake in southwestern China collapsed 10,000 homes in July. In 2003, a 6.6-magnitude quake killed more than 26,000 people in the Iranian city of Bam, in large part because its buildings didn’t follow earthquake codes.

For the world’s poor, safety is a question of resources. “It’s reflecting not only a standard in designing and constructing buildings – it’s reflecting poverty. These people invest as much into their buildings as they can afford,” Faber said.

Structure

The lack of money translates into new buildings that can basically carry only the weight of their materials plus people. Across the board – from structural systems, to materials, connectivity and joints – things are inadequate. Practically speaking, it means that builders sometimes don’t properly attach roofs to walls, and floors to columns.

“It’s not that these people intend to do things wrong. It’s not that we don’t know that this threat is there,” Faber said.

In Switzerland and other developed countries, buildings must be able to absorb the energy of quakes and to warp without collapsing.

Ironically, one of the most effective technologies in quake resistant construction relies on a substance Christopher Columbus discovered in the 15th century when he visited Hispaniola, the island Haiti shares with the Dominican Republic: rubber.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO), a Geneva based group of 158 national standards bodies, has reported on the effectiveness of rubber isolators during earthquakes.

First used in 1969, in the construction of a Japanese school, the pods, which sit under buildings and absorb shocks, have been improved upon. So-called “base isolation” significantly reduced the stress transferred to buildings during quakes in 1994 and 1995 in California and Japan, respectively, the ISO said in a report from June 2009.

In a 2008 quake in China’s Sichuan province, buildings fitted with elastomeric isolators performed notably better than fixed-base buildings, which collapsed. The disaster killed around 70,000 people.

Standards

Haiti, gross domestic product around $1,900 (SFr1,965) per capita, will not be able to afford elastomeric isolators but it can follow some “very simple” principles, Faber says.

They include reinforcing structural components and using shapes that transfer loadings from one wall to another without overloading if a house starts to shake. He recommends developing prototype structures where builders can copy techniques.

Stefan Tangen, director of the ISO’s disaster management committee, agrees it comes down to money: “They need the resources to build secure houses and make infrastructure that fulfils the same level of quality that we have in Europe.”

The ISO’s standards are voluntary although they are often reflected in national laws. “Standardisation and regulation often work together,” Tangen said.

In Haiti there is no automatic guarantee of either. A troubled and politically corrupt country, its administration would on its own be unable to enforce building standards, even if they existed.

“The standard of reconstructed buildings will hopefully be better than what has just collapsed,” said Faber.

“But unless this is seen as a specific aim in the reconstruction and the financing of the reconstruction, the new buildings will not necessarily be better than the old ones.”

Justin Häne, swissinfo.ch

The Richter magnitude scale was commonly used to measure the strength of earthquakes.

It has been supplanted by the moment magnitude scale, a similar logarithmic system used to measure large quakes.

That means that moving up the scale, the intensity of quakes increases exponentially. A quake measuring 6.0 is 31.6 times more powerful than a 5.0 quake. A 7.0 quake is around 1,000 times more powerful than a 5.0 quake.

The ISO is an international body made up of representatives of standardisation bodies from around the world.

It has over 200 committees, including Stefan Tangen’s, which develops protocol for disaster response.

Tangen says it’s no surprise that the response to Haiti’s earthquake has been a challenge.

“Always when something happens, there are problems… You have so many players involved, trying to help,” he said.

He is working for the development and implementation of better standards for disaster response.

“It would be easier to coordinate efforts because we have a better understanding of what we’re doing. But it’s very difficult to do this on an international level because many of the countries have problems just coordinating everything when disaster strikes,“ he said.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.