‘We were so young and idealistic’

César Cabrera is one of many Chilean refugees who found a haven in Switzerland. During the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet he was arrested and tortured. Even today, aged 72, he still has nightmares and wakes in the middle of the night, or goes down into the cellar to read Marx.

September 11, 1973. Exactly 40 years since the military coup in Chile. But in this small room it’s as though time has stood still.

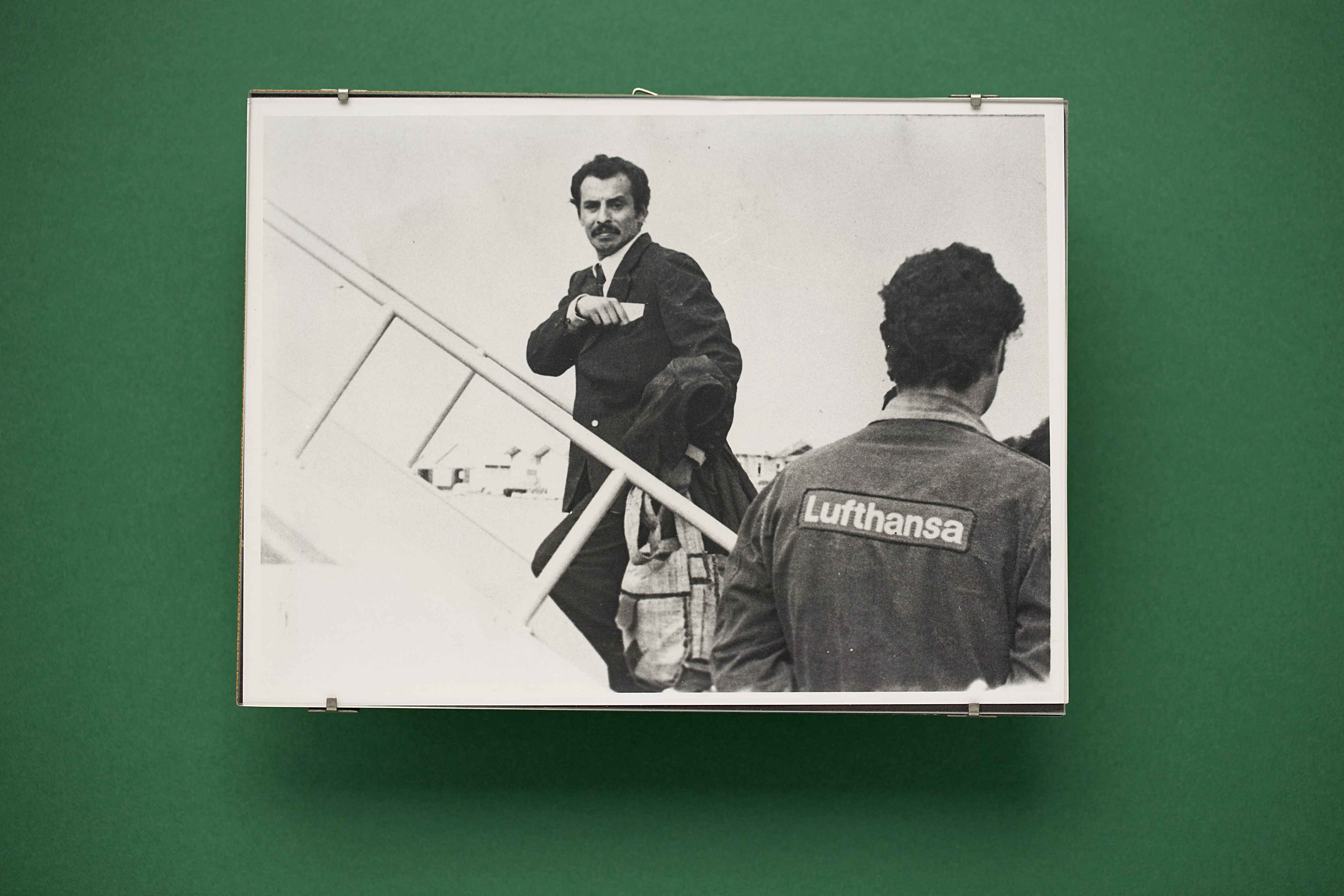

“Do you see that photo up there? That’s me, with Salvador Allende.” Meaningful mementos of Cabrera’s life hang on the wall: a yellowing arrest warrant, a picture taken the day he escaped, his teaching diploma.

“These are the only things I took with me when I fled Chile. I thought: if they shoot me, at least I’ll die with my photos and my books,” Cabrera says solemnly. Then he adds lightly: “We were so young and idealistic back then.”

Cabrera came to Switzerland around 30 years ago, after escaping not one but two dictatorships: first the military dictatorship of Pinochet, then the communist dictatorship of Ceausescu in Romania.

He welcomes me to his home in Rancate in canton Ticino with a big hug, as though we’ve been friends for a long time. He is barefoot, wearing short trousers and a shirt.

Chilean socialism

Cabrera grew up in an intellectual and very political family. Already at the age of 15, he was politically active in Chile’s Socialist Party. He stood beside miners and fishermen fighting for fair wages. He taught children to read and write, applying the theory of “liberation education”.

When Salvador Allende came to power in 1970, Cabrera was named a regional leader. The first few months were marked by a new awakening.

“Allende launched agricultural reform, pushed through the right to education and nationalised the production of copper and other raw materials. With time, however, we were faced with the consequences of boycotts, and the spectre of a civil war was in the air.”

Did Allende aim too high? Cabrera answers categorically: “I’m still convinced that the aim was a democratic programme for the people, and not a revolutionary one. But it’s clear that he was politicising against the interests of multinational companies and the US. And in the middle of the Cold War, at that.”

Arrest and prison

Following Pinochet’s military coup, Cabrera had to go underground. He taught at a school in the countryside, but the military found him there after a few weeks, as part of a large-scale operation.

“They made me undress, and then they beat me in front of the students. I tried to calm down the soldiers, because they had orders to shoot at anyone.”

Cabrera was arrested. After a short stay in a provincial jail he was held in the stadium in the city of Concepción and then transferred to Quiriquina Island, two symbolic sites in Pinochet’s oppressive regime.

Escape

Cabrera survived thanks to his profession and a little bit of luck. “I was the only teacher in the area who hadn’t been killed. To humiliate me, the military regime gave me the job of choreographing a gymnastics performance for the inauguration of a new stadium. I took the job and escaped at the first chance I got.”

In Santiago, he sought refuge at the Italian embassy. “I hid behind a tree and waited until the changing of the guard. Then I ran, jumped onto the only section of the wall not covered in barbed wire and fell onto the other side.” Snipers shot at him, but missed.

After eight months, in March 1976, he received the deportation ruling from the Chilean government. Destination: Romania. The country, under the rule of Nicolae Ceausescu, was one of the few Communist eastern bloc countries which hadn’t broken off ties with Chile.

Cabrera was 35 years old at the time. His passport was given an L stamp: re-entry into Chile forbidden.

Armed struggle

“When I got to Bucharest, I offered my services to the Chilean Communist Party – politically, but also militarily.”

Cabrera was sent to Russia, Cuba, Bulgaria and East Germany, in order to study Marxism and Leninism and to prepare for the armed struggle.

This education as a guerrilla fighter is distinctly at odds with the impression of Cabrera today: an aging teacher with a gentle expression. How does he justify the decision he made at the time?

He takes a glass of water and looks deep into my eyes. “At the time, we were prepared to do whatever was necessary to return to Chile – as free people. It was only after a while that we realised we had become slaves to a childish revolutionary spirit.”

In Russia, Cabrera even learned to drive tanks and followed in vain his dream of becoming a Soviet-style “New Man”. But then came a major setback.

“Claiming that we needed to get field experience, they wanted to send us to fight in Angola and the Congo. But we refused – that wasn’t our war.”

Cabrera paid a heavy price for criticising the Soviet Union and the Ceausescu regime. He was punished with forced labour. And so he decided to escape – for the second time.

This time he was taken in by Switzerland, a country he calls “deeply democratic and irreparably capitalist”. Ironically, this is where he met his wife and found peace.

Marxism as a philosophy

We sit at a table in the garden, with coffee and slices of Chilean cake. Cabrera speaks of his first years in Switzerland: the economic difficulties, the solidarity of families in Ticino, getting to know his future wife, Daniela, the interview for a job as teacher of adult education classes.

“I went to the interview in clothes the priest had given me. They were the clothes of a dead man, but a very elegant one.”

Being able to work again as a teacher saved him. “I would have taken any job – also as a janitor – in order to be back in a school again.” When he was younger, students also came to his garden for Spanish lessons or to discuss history and politics. And from this garden his compatriots organised the resistance.

Today, César Cabrera is no longer involved in politics, at least not in a political party. He often told his students about his fate in Chile – “so that people don’t forget”.

If he’s looking for certain answers, he heads for the cellar to read from Karl Marx’s Capital. Does he still believe in it, after everything that he has experienced?

“I don’t believe in the political ideology, but in Marxism as a philosophy. We’re considered ‘incurable romantics’ – people who still believe that a better world is possible and that one day man will be freed from his chains.”

During the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet from 1973 to 1990 around 40,000 people were hunted down and arrested on political grounds. Around 3,000 people disappeared or were murdered.

Chilean exiles experienced a wide range of fates in Switzerland. Some were held up at the embassy or were deported back as soon as they reached Swiss soil. Others managed to stay in Switzerland thanks to official refugee status and the massive solidarity of the Swiss people.

Between 1973 and 1990, Chilean citizens submitted 5,828 applications for asylum in Switzerland. The exact number of accepted applications is not known. The Federal Migration Office gives no official figures.

According to the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, the Swiss cabinet initially decided to accept only 200 Chilean refugees. This restrictive practice was relaxed after heavy protests.

Over the following decade, some 1,600 Chileans are believed to have received political asylum.

(Translated from German by Jeannie Wurz)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.