A blot on the scientific landscape

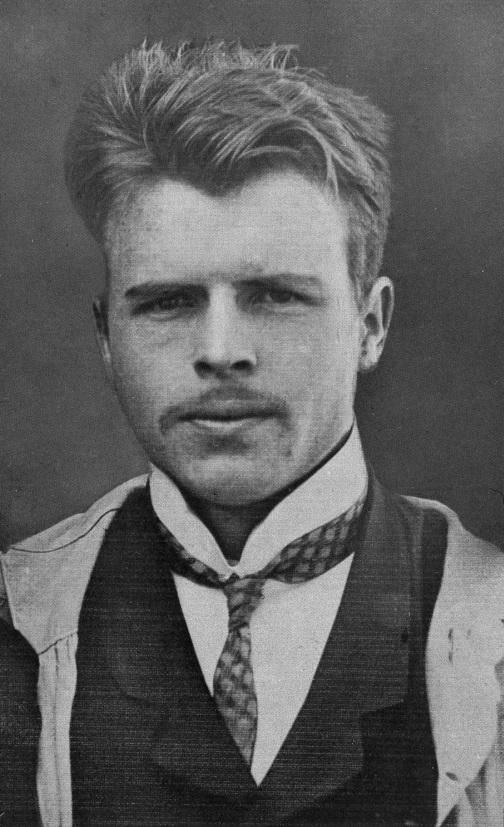

Hermann Rorschach, the Swiss father of the controversial inkblot test, is the subject of a unique exhibition at the University Library, Bern.

Despite the test being little more scientific than palm reading, the display, which marks the 50th anniversary of the university’s Rorschach archive, offers a fascinating insight into the psychiatrist’s life and work as well as an influential chapter in the history of psychology.

“Rorschach was a fascinating personality because he was enormously open towards everything. He had no prejudices against anything and this is mirrored in his very varied research,” Rita Signer, director of the Hermann Rorschach Archives and Museum, told swissinfo.

“In his letters he is also very humorous, and this combination of his respect for the scientific approach and his intuition makes him fascinating.”

Rorschach was born in Zurich in 1884 and died in Herisau, eastern Switzerland, from peritonitis, probably brought on by a ruptured appendix, aged only 37. His main work, “Psychodiagnostik”, was published in 1921, the year before his death.

The archive, the only one in the world devoted to Rorschach, was founded by the Bernese psychiatrist Walter Morgenthaler in 1957 and was substantially enriched seven years ago by bequests from the psychiatrist’s estate.

“Hermann Rorschach: a Swiss psychiatrist between science and intuition” runs at the University Library, Bern, until February 23.

Modern man

In addition to Rorschach’s scientific work, visitors can see photographs, drawings, manuscripts and correspondence, all of which throw light on Rorschach’s personality.

“I think he was a very tender father and this is illustrated in his drawings [for his children]. It was also remarkable that he did work that at the time was more reserved for the mother, for instance changing babies’ nappies,” Signer said.

“He also had very modern ideas regarding gender roles, saying that his wife [who was a physician] should not only be a mother. It was clear for him that he should also participate in the rearing of his children.”

Signer said that Rorschach was more attached to his country than to his countrymen. “He said ‘I’m not very fond of Swiss people – I’m not a very good patriot – but if an enemy ever attacked Switzerland, I would defend Switzerland because of its mountains’.”

Pool of blood?

The exhibition also illustrates Rorschach’s first forays into psychoanalysis, along with his journeys to Russia – “I think his trips there opened his mind enormously,” Signer said – and his research into random images, the basis of his inkblot test.

In the Rorschach test, subjects are handed ten specific inkblots – some black and white, some coloured – and asked to “say what they see”.

Trained observers then rate the reactions on many variables – for example not only what is seen but also whether the subject rotates the image, focuses on only a part of the image or mentions the colours. The psychologist can in theory then pinpoint deeper personality traits, impulses and overall mental health.

In practice however the test fails on two crucial scientific criteria: scoring reliability and validity. A test is reliable if it gets similar results regardless of who measures the responses (not the case with Rorschach); a test is valid if it measures what it aims to measure. The Rorschach test also falls down here, being unable to detect consistently what it claims to be able to: depression, anxiety disorders or a psychopathic personality.

Despite such shortcomings the Rorschach test is still carried out hundreds of thousands of times a year in hospitals, courts, prisons and schools to determine for example which parent should be given custody of a child, whether a prisoner should be eligible for parole and the extent of a child’s emotional problems.

While other scientists had previously dabbled with inkblots, Rorschach was the first to use them to develop theories on people’s tendency to project interpretations onto ambiguous stimuli.

“Early researchers were interested in how much imagination and inventiveness a person had. Rorschach stressed from the beginning that his test was not so much investigating imagination but perception,” Signer said.

Published in 1921, the inkblots were anything but an overnight success. “In Switzerland and Germany the reception was rather cool,” she said. “In fact it was only when the Rorschach test arrived in the United States at the end of the 1920s that the boom began.”

Pseudoscience

While the Rorschach test continues to be defended and used by some psychologists, its one not insignificant flaw is that it is scientifically virtually worthless.

In the United States in the 1940s and 1950s even mentioning inkblots got most psychologists drooling like Pavlov’s dogs, thanks to seemingly miraculous personality readings by Rorschach experts.

Under controlled studies however these “experts” failed miserably and it wasn’t long before more critical scientists realised that Rorschachians were simply, and most probably subconsciously, using cold reading, a technique used by fortune-tellers and others posing as psychics and mediums.

“The readings say more about [the examiners] than the subjects,” to quote Anne Anastasi, the noted differential psychologist.

The exhibition however is devoted to Rorschach the man and not his test, and it succeeds in providing a fascinating profile of one of the most influential, if misguided, psychologists of the 20th century.

Hermann Rorschach was born in Zurich on November 8, 1884.

He entered medical school in Zurich in 1904 and at 22 he decided to become a psychiatrist. During the winter term 1906/1907 he studied in Berlin and travelled to Russia for the first time. During the next term he studied in Bern. In 1907 he registered again at Zurich University, where he graduated in the spring of 1909.

After his exams he returned to Russia and stayed there for several months. He married his fellow student Olga Stempelin, a Russian, in 1910.

Back in Switzerland in 1914 he accepted a position as resident at the Waldau Psychiatric University Hospital near Bern. A year later he was appointed associate director of the asylum at Herisau, in eastern Switzerland.

Rorschach’s book “Psychodiagnostik” was published in 1921. The method presented in it became the Rorschach test.

Rorschach died of peritonitis on April 2, 1922, aged 37, leaving his wife and two children.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.