When in Venice: Swiss pavilion lets things float

Of the 66 national pavilions in this year’s Venice architecture biennale, the one presented by Switzerland is bound to stand out. Curator Hans Ulrich Obrist explains how he and architects Herzog & de Meuron have teamed up with artists to produce a “fun palace”.

The point of departure, shared by all national pavilions, is the theme “Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014”. As director of the 14th International Architecture Venice Biennale, Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas has invited participants to revisit recent architectural history and use it as a toolbox to invent the future.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, recognised as one of the most powerful figures in art, was invited by the biennale jury of the Swiss Arts Council (Pro Helvetia) to curate this year’s Swiss pavilion along the lines of his ground-breaking Utopia Station for the 2003 Venice art biennale.

He has chosen to honour two visionary thinkers who continue to have a profound influence on the design of architecture today, and whom he knew well: Lucius Burckhardt and Cedric Price. But instead of an exhibition, Obrist, with his hallmark curatorial touch, proposes a creative platform at the intersection of art and architecture.

In Obrist’s words, Burckhardt, a Swiss political economist and sociologist (inventor of “strollology”), and Price, a British architect, redefined “architecture as revolving around people, space and performance”. Both passed away in 2003.

In layman’s terms, one might say that they were the first to approach architecture not from a builder’s perspective (how), but in response to the changing needs of the user (why).

Fun lab

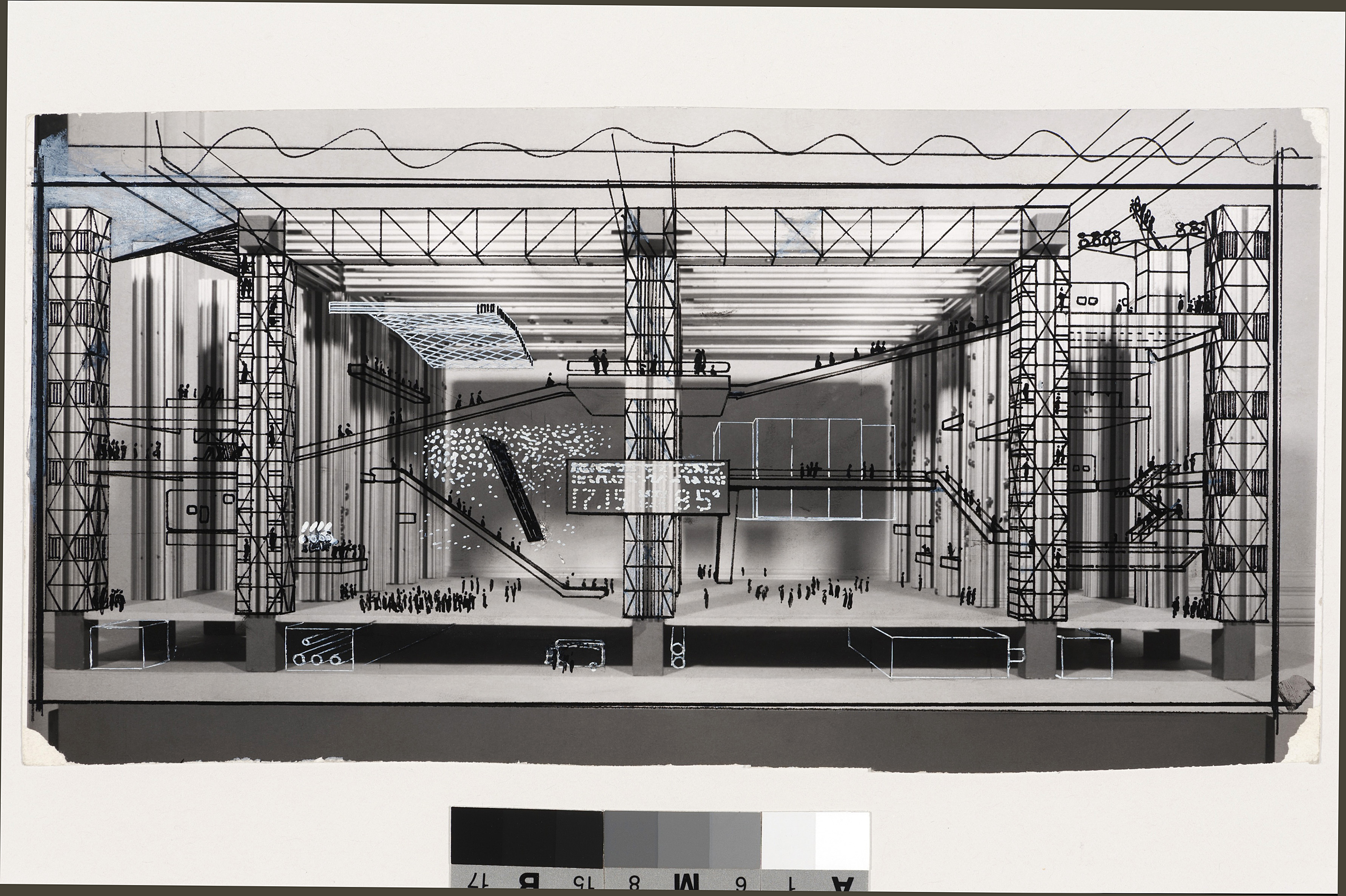

A stroll through a fun palace, as the pavilion project is called, refers to Price’s most influential design. His 1961 Fun Palace pioneered the concept that a building should be impermanent and flexible, and that it should be completed by the user. More importantly, it was to be “a laboratory of fun”.

“Very few architects changed architecture with so few means,” Koolhaas acknowledged of Price, who built very little.

It is a multi-faceted project in which Obrist has included a cocktail of architects, artists and scholars in a collaborative environment.

“Inspired by Sergei Diaghilev, I’m interested in the idea of bringing disciplines together to create a Gesamtkunstwerk, a comprehensive art work.”

Diaghilev, the founder of the Ballets Russes at the beginning of the 20th century, brought all art forms together when he would commission Stravinsky to compose the music, Picasso to create the decors and Nijinsky to dance. He answered: “Surprise me!” to those who aspired to work with him.

Lucius Burckhardt and Cedric Price – A stroll through a fun palace is presented by the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia at the Swiss Pavilion in the Giardini from June 7 to November 23, 2014.

Students from the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, where Burckhardt taught, as well as from other institutions, will enter into dialogue with visitors over the summer and reveal various parts of the archives on different days. The show will function as an architectural school that will reflect on how the contemporary landscape is changing.

Obrist said that the Swiss Pavilion “will be a rendezvous of questions”, with debates and marathons that will allow “information to become knowledge”. The opening days will feature a series of discussions on architecture, landscape design and modes of display.

The number of participating nations at the Architecture Biennale has risen 20% this year.

Creative disruption

According to Obrist, both Price and Burckhardt would have hated the idea of a static exhibition: “They would have adopted a performative way of presenting their archives, which include many drawings. They really wanted artists to be involved, because artists lead a permanent investigation and research into new formats for exhibitions.”

The artists invited to contribute to this year’s Swiss pavilion have all engaged in a dialogue with architecture before. Obrist organised a series of “think tanks” (he also calls them “collaboratoriums”) to reflect on how to develop a mobile display for the pavilion, “one that can always be alive, where different facets of the archives can be discovered every day”.

Obrist first approached Herzog & de Meuron for the part of the exhibition dedicated to their former teacher Lucius Burckhardt, but it became clear that they should also do the overall design of the pavilion.

“Herzog & de Meuron have often worked with artists such as Thomas Ruff and Gerhard Richter, so I thought it would be interesting to bring them together with a younger generation of artists with whom they have never worked before.”

Obrist continued: “The more we talked about it the less ‘physical’ the exhibition became, and in the end, they decided on a concept that will allow, in their words, ‘the mental universe of Lucius and Cedric to be floating in space’.”

What a mental universe might look like in the eyes of architects famous for the Tate Modern in London and the Bird’s Nest stadium in Beijing will be unveiled to the public on June 7.

Co-director of the Serpentine Galleries in London and author of the on-going Interview Project, Obrist has curated more than 250 shows. Architecture has also been part of his curatorial practice since meeting Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron as a teenager. Each summer, the Serpentine commissions a summer pavilion by one of the world’s greatest architects.

For Utopia Station in the 2003 Venice art biennale, speakers, writers, dancers, performers and musicians converged on the idea of utopia to create a project “which oscillated between inside and outside”.

Artist response

“The idea of this exhibition in an experimental format has been an inspiration to the artists,” Obrist observed. He often works with the same group of artists on projects that require a trans-disciplinary approach and a form of disruptive creativity.

The French artist Philippe Parreno, who recently filled the entire Palais de Tokyo in Paris, has won wide acclaim for successfully redefining exhibitions as an experience, a result he obtains by using a diversity of media. For the Swiss Pavilion, he has devised a system of blinds to structure the space.

Parreno is joined by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, who brings her inspirational neons, and Berlin-based Tino Seghal, whose “constructed situations” are about as close to the ephemeral as art can ever be. Carsten Höller, known for his playful installations, has planted a tree.

Other artists will pay homage to Burckhardt and Price, such as Turner-Prize winner Liam Gillick, Dan Graham and the ever-surprising Koo Jeong-a, who will be presenting the installation Cedric & Frand, a work made from 3,000 individual magnets (in 1997 Price presented a show called Magnets on the theme of anticipatory architecture).

A strong visual intervention above the entrance to the Swiss Pavilion by Japanese architects Atelier Bow-Wow will allow a new view of the Giardini from the roof.

Price and Burckhardt would no doubt have been amused: their own visionary thinking has helped transform the Swiss Pavilion into “a stroll through a fun park”, so far removed from the usual fare of static exhibitions.

Cedric Price (1934–2003) was an English architect and influential teacher and writer on architecture. He believed that architectural design should not be subjected to definitive aesthetic statements, but instead provide flexibility to the users. He wrote of his more famous project, the unbuilt Fun Palace (1961): “Its form and structure [resembles] a large shipyard in which enclosures such as theatres, cinemas, restaurants, workshops, rally areas, can be assembled, moved, re-arranged and scrapped continuously”.

The revolutionary Pompidou Centre (1977) in Paris was inspired by the Fun Palace.

Lucius Burckhardt (1925–2003) was a Swiss political economist, sociologist and art historian who invented ‘strollology’, a science of the walk. As a planning theorist, he integrated both the visible and invisible aspects of our cities, political and economic considerations and social relations into the processes. His teachings continue to gain influence, particularly with regard to sustainability, since he promoted the idea of renegotiating objects, instead of adding new ones.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.