Frugal lifestyles on display in Swiss open-air museum

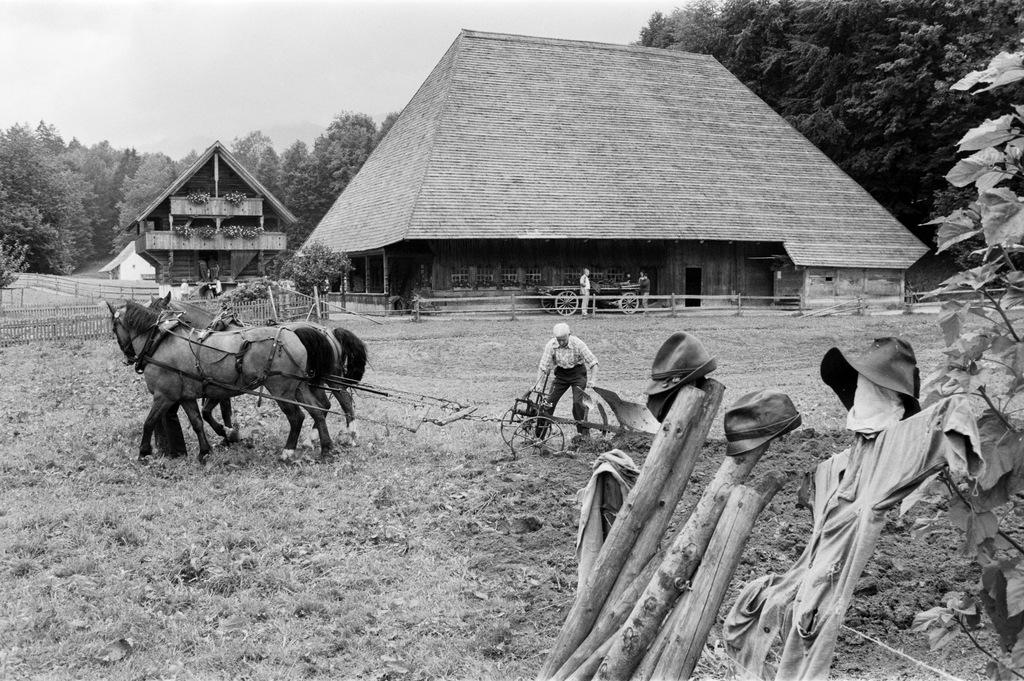

At the Ballenberg open-air museum in the Swiss Alps visitors can experience how the Swiss carved out a meagre existence in earlier centuries.

Surrounded by high mountains, around 110 rural buildings are scattered on 66 hectares of undulating forested land. Grand farm houses with shingle facades or straw roofs, chalets, timbered barns, mortar-free stone houses with shingle roofs, a Mediterranean estate, alpine huts as well as a winegrower’s house create the impression that the building traditions of different nations were gathering here.

But in fact, all houses are Swiss. They were collected from all over the country and faithfully reconstructed.

The museumExternal link near Brienz is open from April 14 to October 31, 2018.

It celebrates its 50th anniversary this year with a series of additional events. A special exhibition is dedicated to the topic of the cow, which played an important role for the Swiss economy.

The museum is also a place of research and study. It houses part of the archive of Swiss farmhouse research.

“Switzerland is a multi-ethnic state,” says Beatrice Tobler, head of science at the Ballenberg museum. “We have completely different geographic and climatic regions which were all influenced by different cultures.”

She adds that the difference in farmhouse styles was also because the houses were constructed with the materials available in the respective regions. Some regions had more wood, others more stones.

It was this multiculturalism, however, that almost prevented the museum from opening its doors.

In the 1930s, the Pro Campagna organisation suggested following the example of other countries and launching an open-air museum.

But Switzerland’s Heritage SocietyExternal link, which oversees the preservation of listed buildings, was opposed to the idea. It argued that the dwellings were too different to display in one location without appearing artificial.

Another worry was that an open-air museum would remind people of the dubious 1896 National Exhibition in Geneva where 200 Sudanese and 300 Swiss were displayed in a “Negro Village” and a “Swiss Village” respectively. Creating such a human zoo would be a problem. The plan to convert a residential area on Lake Brienz in the Bernese Oberland into an open-air museum was abandoned.

In the end, an agreement was found to build the museum on the uninhabited Ballenberg hill just outside the small town of Brienz.

In 1968, a foundation was set up to search for historically valuable buildings that could not be maintained in their current location. The museum finally opened its doors in 1978. To this very day, the museum only collects houses that are under threat due to traffic or building projects.

Inside the houses, original furniture as well as articles of daily use and tools are on display.

More

Open-air museum celebrates heritage

All objects date back to the era before the mechanisation of agricultural which came about around 1950.

The oldest house was built in 1336, the newest around 1900. In an effort to keep the conditions as close to reality as possible, the exhibitors kept the shabbiness of the buildings, the cramped living conditions as well as the very basic furniture.

The gardens are also cultivated and planted according to old traditions. Most of the agricultural work is done by horse and cart.

The operators are eager to preserve ancient knowledge and skills. For example, they plant soapwort and make washing-up liquid from it or produce linen from the flax that grows in the garden.

With raw materials being rather scarce in Switzerland, agriculture was very important. Up until about 1850, most Swiss were employed in the agricultural sector and worked in farming, animal husbandry, forestry, viticulture or fishery.

Strictly speaking, most of them were not only farmers. If they owned any land at all it was usually very small and they typically worked for other farmers.

“Many families had other jobs in the weaving, wool or embroidery industries. They had to sell something so could purchase essential goods, such as salt,” Tobler explains.

Under the workshop system, agents provided the small farmers with materials which they would ply and sell them back to the agents. Visitors of the museum can watch craftspeople doing basketwork, forging, braiding, spinning, weaving and woodcarving.

There were also wealthy regions in Switzerland, especially in the cities. This is reflected in the grandeur of the displayed manufacturer’s mansions and big farms.

A large part of the rural population lived in destitute conditions though, and the shabby day labourers’ houses as well as the modest mountain huts remind us of that poverty. “Most of the houses appear pretty today, but once you imagine living there you quickly understand the poverty these people lived in,” says Tobler.

A big part of the rural population moved to urban areas to find employment in the 19th century.

The museum is currently struggling with dropping visitors’ numbers. The problem is that unlike other open-air museums in neighbouring Germany or Scandinavia, the Ballenberg museum is not near a big city but tucked away in the mountains of the Bernese Oberland.

Contact the author of this article @SibillaBondolfi on FacebookExternal link or TwitterExternal link.

Translated from German by Billi Bierling

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.