Particle physicist shuns hyperactive investments

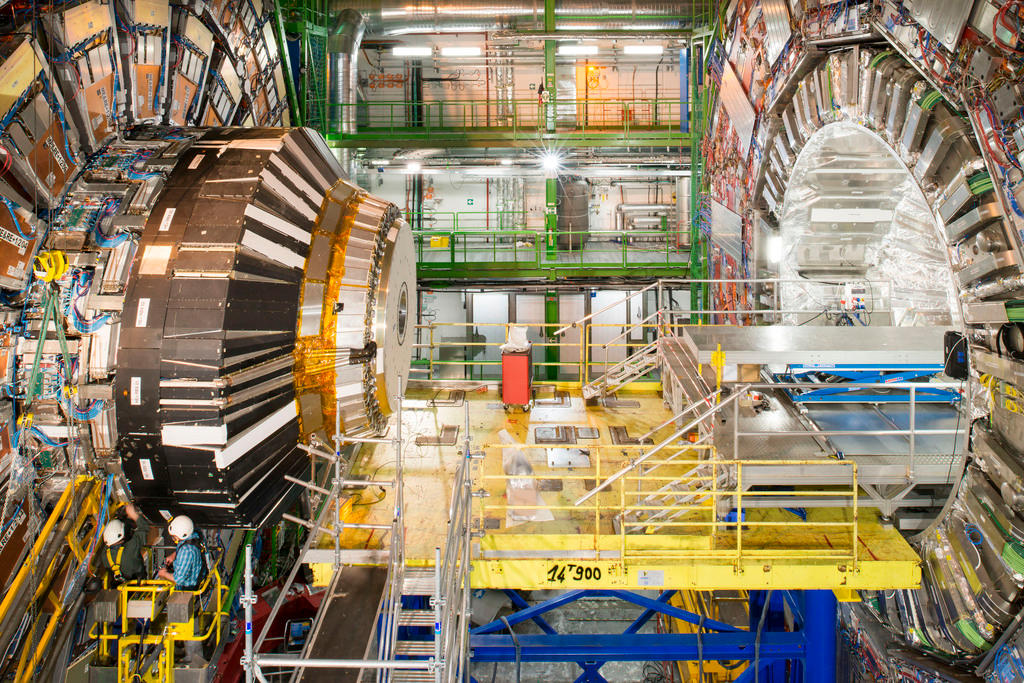

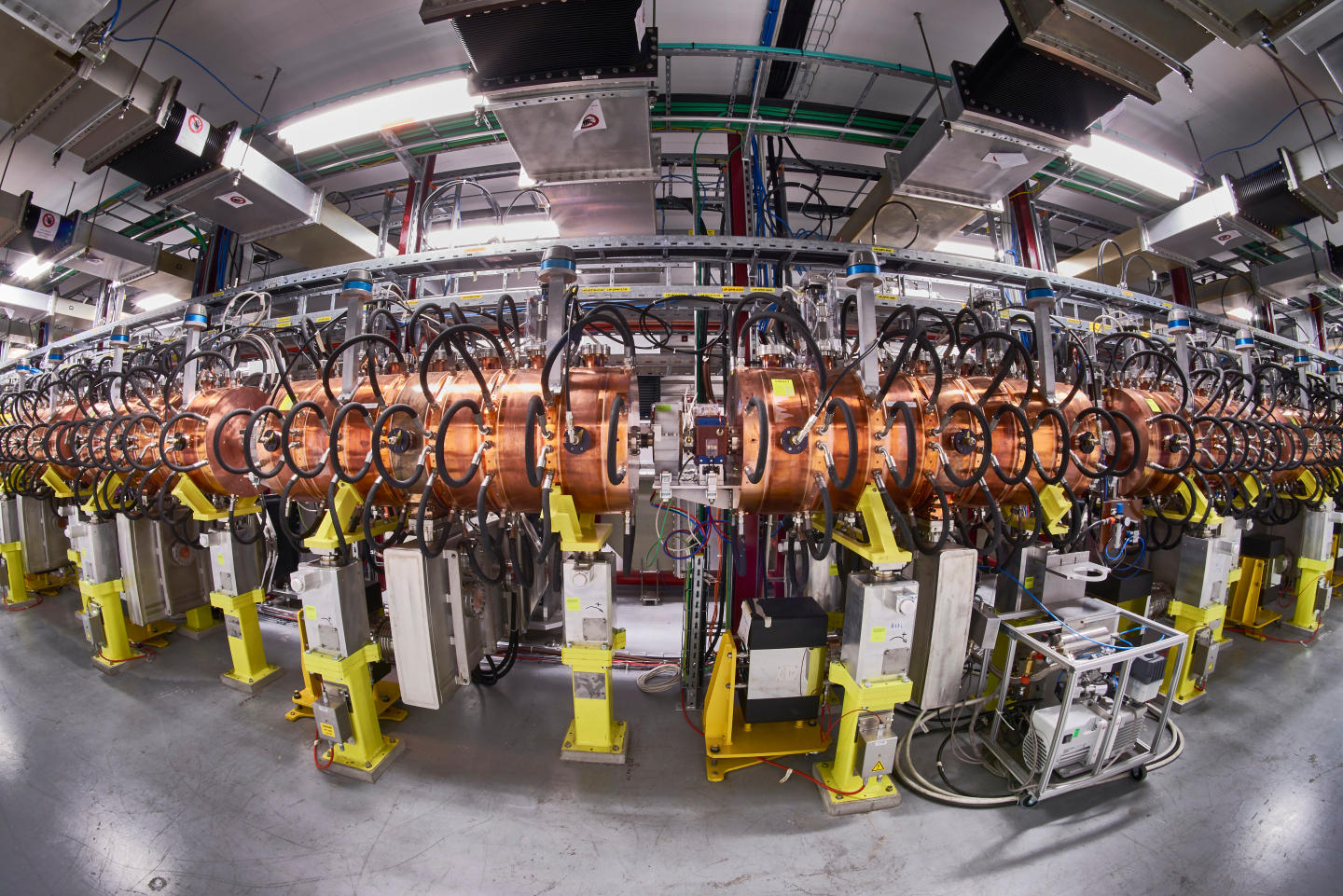

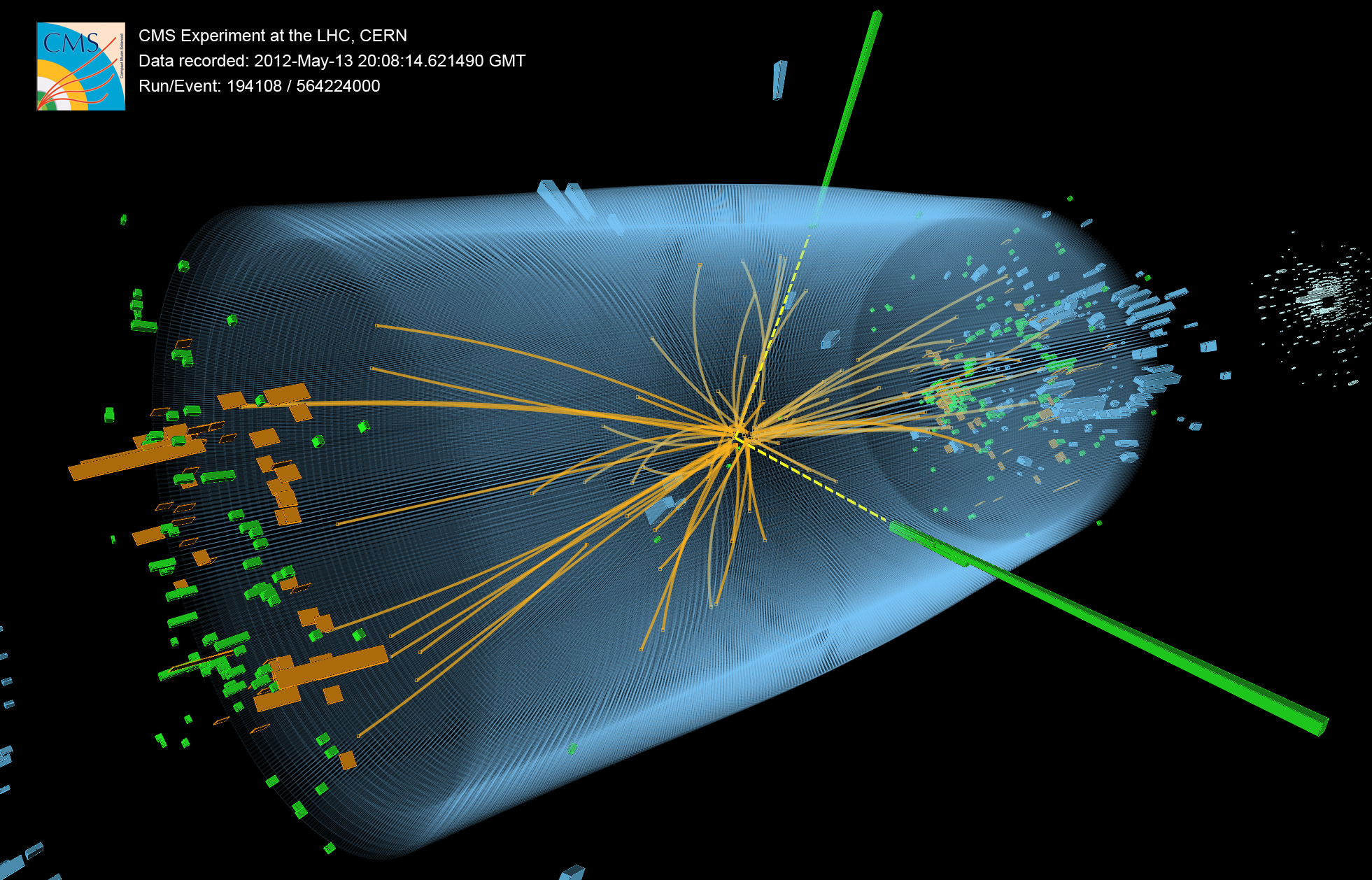

Cern practises cutting-edge science but its pension fund is surprisingly risk averse. The prestigious nuclear research centre near Geneva, is best known for blasting atoms around its Large Hadron Collider, a 27-kilometre tunnel that forms the world’s largest machine.

The organisation, founded in 1954 and straddling the border between Switzerland and France, declares boldly on its website: “What is the universe made of? How did it start? Physicists at Cern are seeking answers, using some of the world’s most powerful particle accelerators.”

Against this backdrop of cutting-edge science, it seems counterintuitive that the woman charged with ensuring a comfortable retirement for Cern’s community of 3,600 scientists, researchers and support staff is extremely risk averse.

Elena Manola-Bonthond, chief investment officer of Cern’s $4 billion (CHF4 billion) pension scheme, says: “I don’t like hyperactivity in investment management, or rushing into making decisions. There is an atmosphere in the investment world that you have to react, react, react. But hyperactivity is not the ideal way to approach investing.”

Ms Manola-Bonthond, a particle physicist by training, worked in Cern’s risk management and IT operations, before moving to the pension fund to help improve its investment framework in 2011. The mother-of-two was promoted to chief investment officer in 2015.

More

Financial Times

External linkNo hedge funds

Speaking to the Financial Times from her office in Geneva, she rules out several topics of discussion, including her views on the hedge fund industry, her scheme’s funding ratio and its approach to monitoring corporate governance.

The Cern pension scheme has in fact reduced its exposure to hedge funds significantly over the past 18 months, from 16% of its assets under management at the end of 2014 to around 10% today, according to its latest financial statements.

The trend is not unusual. Hedge funds have come under fierce scrutiny from the world’s largest investors over the past decade due to concerns about high fees for pedestrian performance.

Ms Manola-Bonthond initially declines to comment on why her scheme’s hedge fund allocation has declined.

After some probing via email, she later explains the change was due to the fund’s decision to move away from so-called absolute return strategies that attempt to generate positive returns in any market environment, in favour of investments that provide more diversification.

The scheme remained invested in several high-profile hedge fund companies at the end of 2015, including Brevan Howard, Tudor Investments, Bridgewater and Citadel.

Ms Manola-Bonthond is also reluctant to discuss the European Central Bank’s record-low interest rate policy, which critics blame for hurting the investment performance of retirement funds.

No politics

“As a member of Cern I don’t want to say anything political,” she says. “It is clear that low interest rates pose a challenge both for pension funds and for asset managers. But policymakers, I believe, are making the best possible efforts to keep the situation under control.”

The scheme’s funding ratio, which demonstrates to what extent it will be able to pay pensions to workers in future, is another sensitive subject. The latest accounts indicate that, by international accounting standards, its ratio of assets to liabilities is worryingly low, at just 40%.

The accounts, published last May, go on to say that international accounting standards “produce a very conservative funding ratio that is inappropriate for assessing the health of the fund”. According to Cern’s alternative methodology, its funding ratio is 73%.

Ms Manola-Bonthond, who grew up in the Croatian town of Dubrovnik before studying particle physics at Cern in her twenties, shies away from discussing these figures.

The 47-year-old is more comfortable discussing the “fads” she fears some investors have been drawn into in a bid to achieve better returns.

Although Cern’s pension scheme invests in some of the increasingly popular illiquid asset classes such as private equity and debt, she believes other investors are “cramming” into these areas, irrespective of the risks. “This is the big temptation of the current low-growth and low-yield environment,” she says.

“The asset classes that one really has to be attentive to are those where you don’t see volatility, and then one day [produce] a surprise. That means being extremely selective when choosing illiquid alternatives. There are very few shortcuts.”

Smart-beta funds

Ms Manola-Bonthond is particularly concerned about the rise of smart-beta strategies that aim to provide market-beating returns at low cost through index-tracking vehicles. Smart-beta funds drew a net $24 billion from investors in the first three months of 2017, a 2,000 per cent increase on the net inflows recorded over the same period last year.

“When you see a lot of money flowing in, you can [bet] that performance will not be [what] is advertised,” she says. “Smart beta is very good on paper, but there can be a number of untold risks there.”

To help Cern’s pension fund prepare for painful market surprises, Ms Manola-Bonthond has increased the scheme’s use of stress tests. These aim to measure the impact of unexpected developments, such as a stock market crash, on the fund’s long-term performance. She recognises the limitations of the results, however.

“Whether the reality will be similar to a stress test is difficult to answer,” she says. “The macro outlook is very difficult because valuations are very high.

“The challenge for us today is to accept the reality that we are in a low-yield environment, and refrain from taking risks we cannot master. The permanent loss of capital is the most important risk for a pension fund.”

Ms Manola-Bonthond insists she does not miss her scientific career.

She, too, is seeking answers to the world’s mysteries, she adds. “[My current role] is extremely interesting. You have a window into the world; you are connected with the economic reality of the entire planet. This is the most fulfilling dimension of the work.”

Born: 1969

Total pay: Not disclosed

Education: 1988-93 – MSc (physics), University of Zagreb, Croatia 1993-96 – PhD (particle physics), University of Savoy, France 2010-12 – Executive MBA (international management), University of Geneva, Switzerland

Career: 1996-98 – Research physicist, Cern, Geneva 1998-2010 – Various management positions related to safety and quality management for the Large Hadron Collider, Cern 2011-12 – Project leader for the investment framework, Cern Pension Fund 2013-14 – Head of strategic planning, Cern Pension Fund 2015 to present – Head of investments, Cern Pension Fund

Cern Pension Fund

Founded: 1955

Assets under management: CHF4 billion ($4.1 billion)

Employees: Nine

Headquarters: Geneva

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2017

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.