Could Nobel Prize for malaria drug ruin TCM?

Tropical health experts in Switzerland have welcomed the awarding of the Nobel Prize for Medicine to Youyou Tu for her malaria medicine, but in China, the recognition could have double-edged consequences.

The decision to award the prize to China’s Youyou Tu – co-winner for developing the malaria treatment Artemisinin – calls into question whether the reputation of traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is threatened by the success of her medicine.

Even though Tu’s award was applauded in China, it has also sparked some debate over whether its production truly follows the traditional Chinese method.

For the former head of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Marcel Tanner, there was no doubt that Tu should receive the prize.

More

Researching malaria on the ground

“If you consider how many people have been saved from the deadly clutches of malaria by Artemisinin, then given the obvious impact, no more needs to be said.”

For Xudong Wang, a professor at the Medical University of Nanjing, the Nobel Prize for Tu was also self-evident. But he was less enthusiastic than Tanner, expressing concerns that traditional Chinese medicine could suffer reputational damage because of the popularity of Artemisinin.

Inspired by TCM

“Take a handful of one-year-old wormwood, soften it in twice as much water, squeeze the plants out and drink the juice.” This sentence from a handbook on treating acute illnesses by the Chinese Taoist and alchemist Ge Hong (c. 280-340) was a revelation to Tu.

Wormwood, the active component of Artemisinin, forfeits much of its antimalarial effect if it is extracted through boiling, the traditional method used in Chinese medicine.

Artemisinin, which is produced without heating, achieves a success rate of more than 90%.

So the means of extracting the medicine is decisive. And this fact led to controversy over whether Artemisinin is a chemical medicine or a product following a traditional Chinese approach.

The Nobel Prize committee justified its decision to award Tu the prize as follows: “We are awarding this year’s Nobel Prize not to traditional Chinese medicine, but to a researcher who developed a new treatment inspired by traditional medicine.”

More

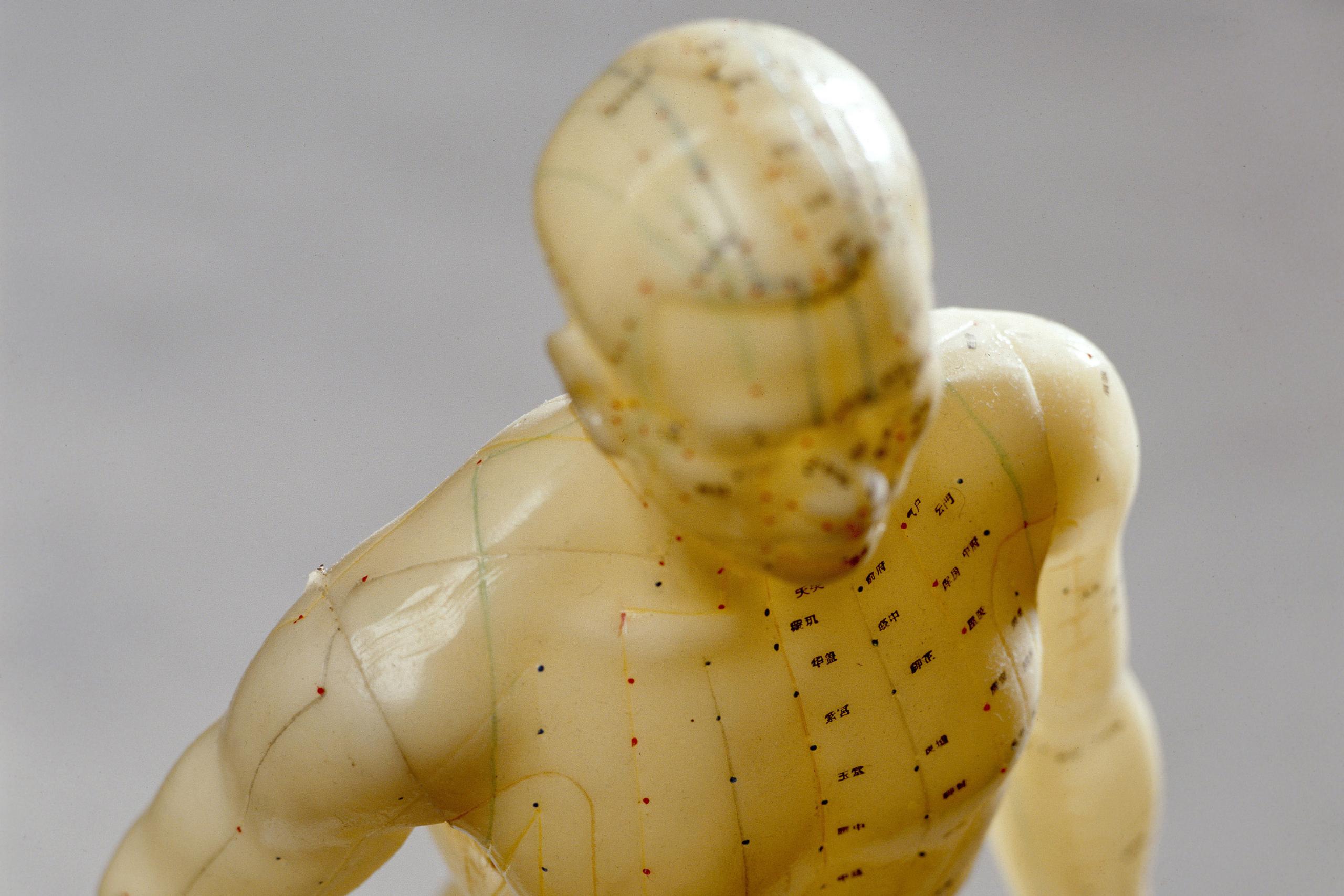

Traditional Chinese medicine

Tanner, who today lectures as a professor at the University of Basel, judges Artemisinin to be a product of both TCM and pharmacology. He doesn’t understand the criticism in China: “It is a mistake to discuss this. The method isn’t important, just the fact that Artemisinin is a wonderful discovery.”

“Even if Tu produced Artemisinin with modern pharmacological methods, traditional Chinese medicine cannot be excluded from the discussion – she was inspired by it,” stresses Wang. “The Nobel Prize committee correctly recognised this fact.”

Three ‘flaws’

Equally hotly debated in China is the pharmacologist’s career. Tu has no doctorate, nor is she a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and she doesn’t have research experience abroad. Despite her lack of academic credentials, the scientist has saved millions of lives with her medicine.

“In this respect, Youyou Tu is actually an unknown,” Wang says. “By Chinese standards, Tu in many ways doesn’t stand out in the crowd, which means that her Nobel Prize has aroused unease and envy in some quarters.”

“Abroad, it is the discovery that counts and not social status. On this point, I pay my respects to the Nobel Prize committee’s decision. For some of the scientific institutions in our country this is a real wake-up call.”

Tanner calls for a certain flexibility among institutions on this point: People without titles who have achieved extraordinary successes of enormous social value should receive honorary titles. “If Youyou Tu was working in Switzerland, she would have received an honorary doctorate immediately.”

Has TCM been displaced?

“This Nobel Prize is not necessarily a good thing for TCM. It could lead it down a blind path in the future,” cautions Wang, who is currently working in Switzerland.

The fact that Tu’s experimental methods linked with TCM led her to the Nobel Prize “could make a Western style of TCM the norm,” he fears.

This could “influence Chinese policy towards TCM, so that the state gives more financial and political support to laboratory research.”

“Trying to analyse holistically oriented TCM with Western reductionism could mean a death sentence [for TCM],” Wang warns.

Artemisinin has saved the lives of millions of people. Its significance cannot be weighed against a Nobel Prize. Is Tu now a scholar, or not? Is it really so important whether her discovery is a TCM medicine or a product of modern pharmacology?

Professor Wang puts it in perspective. “If there were no more diseases, then the question of who wins the Nobel Prize would also be obsolete.”

Road to Success

Traditional Chinese Medicine, or TCM, has won increasingly broad acceptance in Switzerland in the past few years. In certain cases, it is covered by health insurers as part of basic health insurance. According to Xudong Wang of the Medical University of Nanjing in China, who is currently working in Switzerland, the number of TCM practitioners in Switzerland has multiplied from a few dozen to several thousand. Simon Becker, the rector of Chiway, the Academy for Acupuncture and Asian Medicine in Winterthur, says acceptance is still increasing. Certificates awarded by his centre are recognised nationally. Becker is delighted about Youyou Tu’s Nobel Prize: “This shows that TCM still has many hidden treasures to be discovered.”

Malaria and Switzerland

Switzerland is involved in many projects to combat malaria. As early as 1948, the Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller discovered that the controversial insecticide DDT could be used to fight mosquitos and reduce malaria. He won the Nobel Prize for Medicine as a result.

The Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute was the first institution to use Artemisinin to treat children in Africa.

Translated by Catherine Hickley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.