Switzerland – a trading paradise?

How do Swiss-based commodities giants Glencore or Vale operate in the field and what are the consequences of their work for those living there? A new documentary by respected Swiss director Daniel Schweizer takes a rare look behind the scenes of this industry.

“Today some of the biggest extraction and trading firms are based between Geneva, Zug and Lausanne. Switzerland has a great responsibility accepting them here and monitoring them so little,” declared SchweizerExternal link at the world premiere of his new documentary Trading ParadiseExternal link, shown at the Visions du Réel film festival in NyonExternal link last weekend.

After skinheads and neo-Nazis, environmental damage and gold, Schweizer tackles another sensitive topic for Switzerland: commodity trading.

The filmmaker travels to mining operations run by GlencoreExternal link in Peru (Antacappay) and Zambia (Mopani) and another belonging to ValeExternal link in Brazil (Carajàs). The first two result in rare footage inside the mines.

From snowy Lake Geneva, we move to the arid, brown rolling mountains of southern Peru with trucks thundering outside Glencore’s huge open air Antacappay mine.

The film cuts between officious security guards and locals who complain about the pollution of their rivers and land from mine waste water.

Interviews are interspersed with recent TV images from violent demonstrations against the mine in Espinar province, and a 2013 news report showing dead animals that farmers claim had ingested food or water contaminated with heavy metals coming from mining activities. However, these claims were recently rejected by a study commissioned by the Peruvian National Service of Agricultural Health.

“I believe as human beings we have the right to live healthily. But here the mining company treats us like animals,” says elderly farmer Melchora Surco Rimach, adding she has received death threats for being outspoken about pollution.

The film then moves to Zambia following a Swiss researcher from the Swiss NGO Berne DeclarationExternal link who is gathering information on one of Africa’s largest copper mines – the Mopani Mine in the Mufulira region, bought by Glencore in 2000.

Locals there complain about air pollution, in particular a poisonous sulphuric acid wind named ‘Senta’, which they claim destroys harvests and damages health. The plant has emitted sulphur dioxide since its creation in the 1930s.

“People breathe in sulphurous emissions as if they were oxygen. This air is toxic. When Senta blows at night people suffocate and die in their sleep…They don’t want to pay attention to our situation,” says Maggret Chsanga Waya, who lives in Kankoyo in a small rundown shack opposite the huge industrial copper mine.

Glencore executives reject the charges, saying they have invested $550 million upgrading a system to capture 97% of sulphur dioxide emissions at the plant.

From his headquarters in Baar, canton Zug, Chief Executive Officer Ivan Glasenberg defends the company’s social and environmental record.

“We respect human rights in the countries where we operate totally,” Glasenberg declares. “We have our own principles to respect human rights in the countries where we operate and we do that, and we do more than that, as we take care of the families and the population in the area of the mines in which we operate, not just the people who work at the mines. On environmental standards we don’t just follow the country standards; we follow international standards.”

In the second half of the film, Schweizer travels to the Carajàs mine in northern Brazil, the largest iron ore mine in the world owned by the multinational Vale. Information there is harder to gather, however, as Vale, which has its administrative headquarters in St Prex in canton Vaud, refuses to talk to him or grant access to the Brazilian site.

Instead the filmmaker meets Xikrin Indians, who are unhappy about the expansion of the mine and threats to their way of life. They talk of how the firm has driven them from their ancestors’ lands. As they are interviewed in their traditional costume and make-up, the thud-thud-thud of heavy machinery can be heard beyond the thick forest.

From there we return to Switzerland, described as an ideal location for the multinationals as it provides access to commercial banks, fiscal privileges and a light regulatory touch.

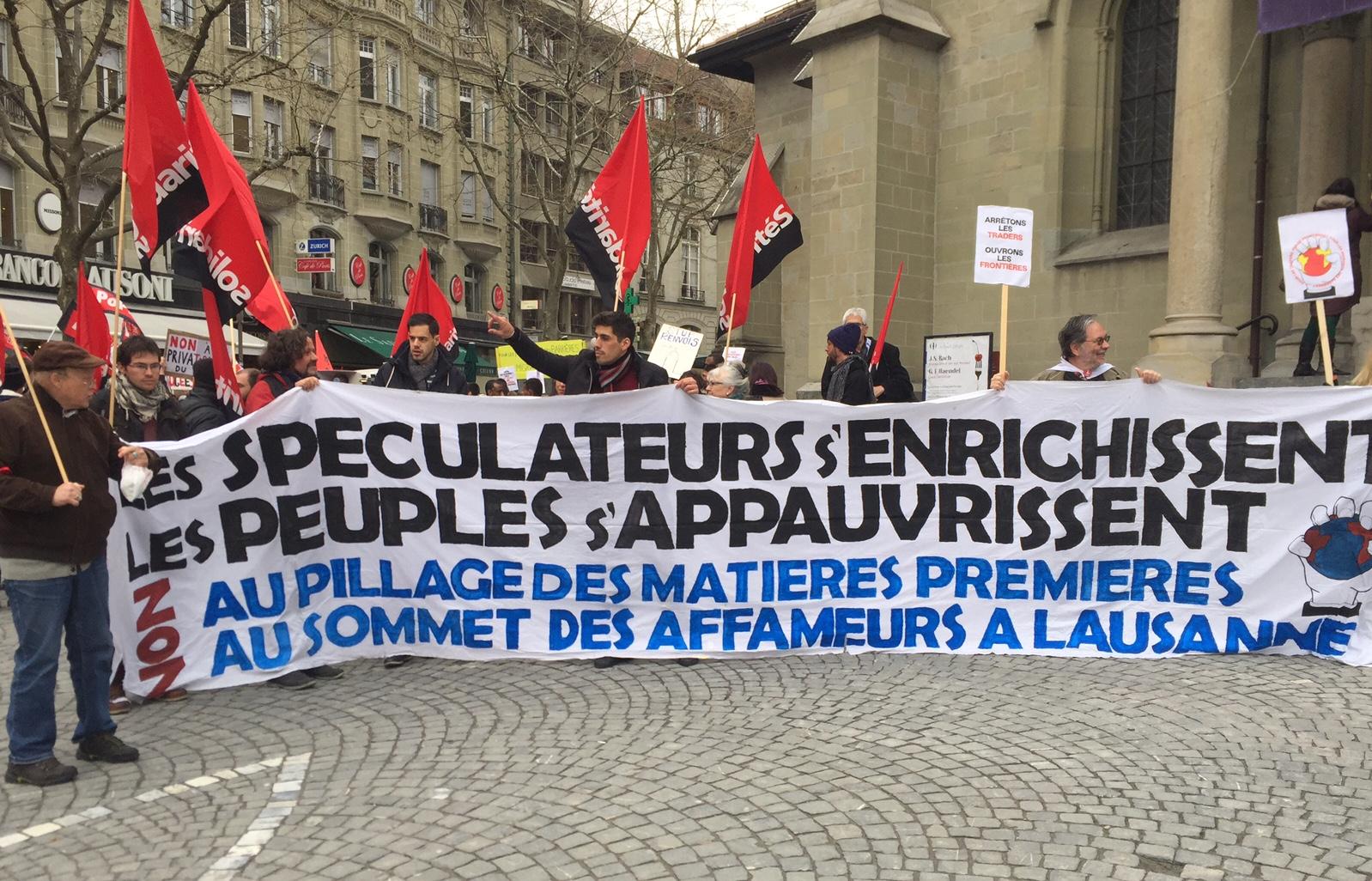

In Lausanne, the camera moves back and forth between traders sipping champagne at the 2014 Financial Times Global Commodities SummitExternal link inside the five-star Beau Rivage hotel in Lausanne and protesters outside who are stopped in their tracks by police officers and pepper spray.

In March 2013, the Swiss government published a controversial reportExternal link on the commodities market. It recognised the importance and risks, but stopped short of drafting separate legislation for the sector, preferring voluntary non-binding regulations.

Schweizer follows a delegation of eight Swiss parliamentarians who visit Espinar in Peru in 2014, which resembles more of a tourist trip than an official mission. One MP criticises the intimidation by Glencore, but others praise the mining industry’s achievements or urge the firm to be more transparent.

While calls for change are coming from all sides, Stéphane Graber, secretary general of the Swiss Trading & Shipping AssociationExternal link argues that actually much is already being done: “The sector has developed massively. But it has also developed a lot with regard to social responsibility, risk management and due diligence.”

But activists say the efforts are not enough and more pressure is needed from civil society to make firms live up to the corporate social responsibility claims found in their brochures and that the situation on the ground is improved.

Changes could be afoot. The 140,000 signatures for a people’s initiative dubbed “For Responsible Business”,External link directly aimed against the Swiss-based commodities sector as well as other multinationals, will reportedly be handed in at the Federal Chancellery in October. This could force a nationwide vote – but not before 2018.

Schweizer says Trading Paradise, which is set to get a nationwide release later this autumn, is his personal contribution to this ‘big political debate [on commodities trading] still to come”.

In the space of only a few years Switzerland has turned into a major commodities trading hub. The small alpine state is home to about 500 companies specialising in this field, including giants such as Glencore, Vale, Cargill, Vitol and Trafigura.

The firms, which are mostly based in Geneva, Zug and Lausanne, employ about 10,000 people and contribute nearly 4% of the country’s GDP. Approximately a quarter of all raw materials are traded through Switzerland, including 35% of crude oil, 60% of metals, 35% of grain, and 50% of coffee.

Firms’ reactions to Trading Paradise

Glencore: “As part of our stakeholder engagement, we welcomed the opportunity to take part in the making of the film. We look forward to continuing to work with the producers to address certain inaccuracies before the film’s general release in the autumn.”

Vale: “Vale will be happy to share with you its view on the documentary, but only once it will be released in autumn, as no-one at Vale has seen it so far.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.