Cross-border workers: a contentious Swiss reality

The number of cross-border workers has ballooned in Switzerland with the introduction of the free movement of people. Well-accepted in the Jura and in German-speaking Switzerland, they are sometimes the victims of violent attacks in Ticino and Geneva.

“Enemies of Genevans! Cross-border workers: enough! Give Genevans hiring priority!”

The Geneva Citizens Movement – the second largest party in canton Geneva – has already chosen its publicity campaign for the October 6 local elections, nominating cross-border workers as its prime target. Its sister party in canton Vaud is just as explicit about its intentions on its website:

“The wave of workers coming from France leads to the degradation of infrastructure, increases pollution, puts pressure on salaries and forces many of our citizens onto social welfare.”

“All these comments are difficult to accept, especially for the people who have spent many years investing in their company and in the country where they work,” says Jean-François Besson, general secretary of a non-profit group that represents French cross-border workers in Switzerland.

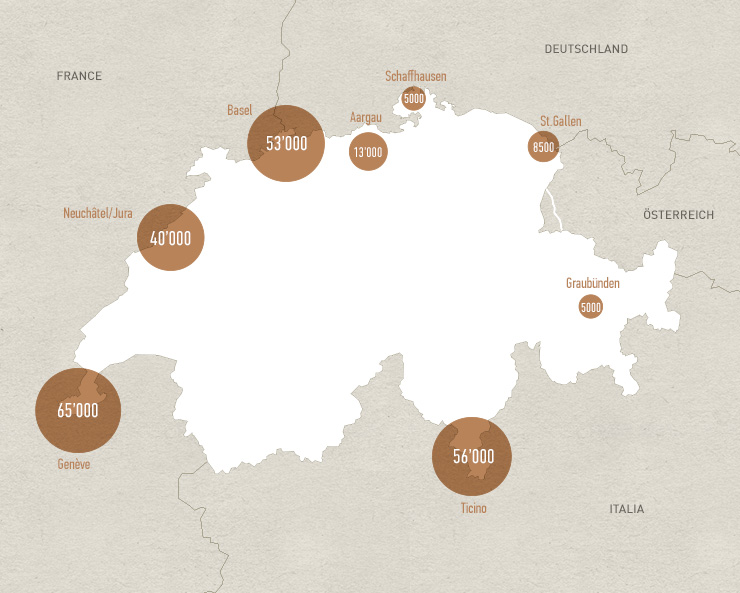

In Geneva, almost a quarter of the workforce is made up of cross-border workers. They hold positions in all sectors of the local economy, such as retail, health and financial services, as well as within international organisations. Each day, around 65,000 foreign workers cross the border separating Geneva from France – a figure which has doubled in the last decade.

The negative effects of the free movement of people have been limited in Switzerland since 2002, according to a report published on June 11 by the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), which analysed the effect on the labour market, particularly in the border regions.

“We did not observe a significant difference in the evolution of salaries or the unemployment rates in border regions compared to the rest of Switzerland over the last 11 years,” Peter Gasser, director for the free movement of people at SECO, told swissinfo.ch.

In April, a study published by the employment observatory at the University of Geneva debunked the theory that cross-border workers take jobs from the Swiss. According to the study, unemployed Swiss are often not qualified for the jobs available in the Geneva region.

However, the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions maintains that the pressure on salaries caused by the free movement of people is a reality, particularly in the sectors not covered by collective work agreements. For Swiss trade union Travail.Suisse, greater regulation is needed in the regions with high numbers of immigrants or with a lot of cross-border workers.

Several initiatives, cantonal and federal, have been launched in recent years calling for the implementation of minimum salaries.

Overloaded infrastructure

“The rejection of cross-border workers is primarily due to overloaded public transport and a shortage of housing, rather than to a lack of jobs,” says Besson. “In fact – and studies prove it – this workforce has been indispensible to the phenomenal development of Geneva over the last few years and has not taken jobs away from the Swiss.”

Claudio Bolzman – professor at Geneva’s Institute of Social Work and author of Daily migrants: cross-border workers, published in 2007 – recalls that tensions have been present on both sides of the border since the 1960s and ’70s.

The situation is less tense in Basel, a city located at the intersection of Switzerland, France and Germany. It has accommodated a large cross-border workforce for many years.

French-German Cédric Duchêne-Lacroix lives in France. His home is just a 15-minute bike ride from his job at Basel University, where he is a researcher with the department of sociology.

He can think of several reasons why Basel is more tolerant of cross-border workers.

“The population is less concentrated in Basel than in Geneva, and the increase in cross-border workers has been more measured – 53,000 including Basel-Country, just 7,000 more than in 2002. So it doesn’t provoke the same feelings of invasion. This is surely due to a transport system that is less congested, but also to the economic structure of the city.”

Basel, open city

While the unemployment rate in Geneva is at 5.5 per cent, it’s at four per cent in Basel. A lot of new cross-border workers in Basel are Anglophones working for the large pharmaceuticals companies for which Basel is known.

“They are both international cities, but in Geneva the cost of living is higher and a section of the working class feel they have been left out compared to the diplomats, the wealthy and the cross-border workers,” says Duchêne-Lacroix, adding that Basel has historically had a more peaceful existence with its neighbours.

“Basel has for a long time been considered one of the most open cities in Switzerland. Several monuments are dedicated to its strong links with Alsace.”

The free movement of people agreement with the European Union entered into force on June 1, 2002. The restriction obligating cross-border workers to live in border regions was lifted on June 1, 2007.

Businesses do not have to adhere to work permit quotas or give preference Swiss nationals during the recruitment process. Cross-border workers automatically obtain a work permit (G) upon signing a work contract, with the only condition being that they must return home for at least one night a week.

Cross-border watchmakers

Like Geneva, canton Ticino has seen a rapid increase in the number of cross-border workers from Italy – up 75 per cent to 56,000 since 2002 – and as such is also in the sights of the populist right. Factors such as the seemingly endless traffic jams to get through customs at Chiasso, a higher unemployment rate (4.6 per cent) compared to the rest of Switzerland (3.1 per cent) and a desire to distinguish themselves as Swiss compared with their Italian big brothers all work in unison to build resentment towards cross-border workers and its political manifestation.

“The Swiss identity often carries a negative connotation in relation to its neighbours, that is not specific to Ticino,” says Paola Solcà, director of the migrant research centre at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland (SUPSI).

Salary undercutting is also a bigger problem in Ticino than elsewhere in Switzerland, according to a recent report on Swiss-Italian television, RSI. Ticino’s parliament has written to the federal government contesting the results of a study which confirmed the benefits of the free movement of people, including in the border regions (see sidebar). Since the beginning of these agreements, explains Solcà, cross-border workers no longer just compete between each other for low-skilled jobs, but are now more present in professional sectors such as medicine and finance.

In the Jura, bastion of the Swiss watch making industry where cross-border workers have doubled to 40,000 over the last decade, the situation falls somewhere between that of Basel and Geneva, says Patrick Rérat, researcher with the institute of geography at Neuchâtel University.

“Everyone agrees that the watch industry could not develop without cross-border workers because 60 per cent of employees in this sector do not hold Swiss passports. At the same time, there are increasing concerns about traffic jams, salary undercutting and the competition for jobs between cross-border workers and less-qualified Swiss workers.”

(Translated from French by Sophie Douez)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.