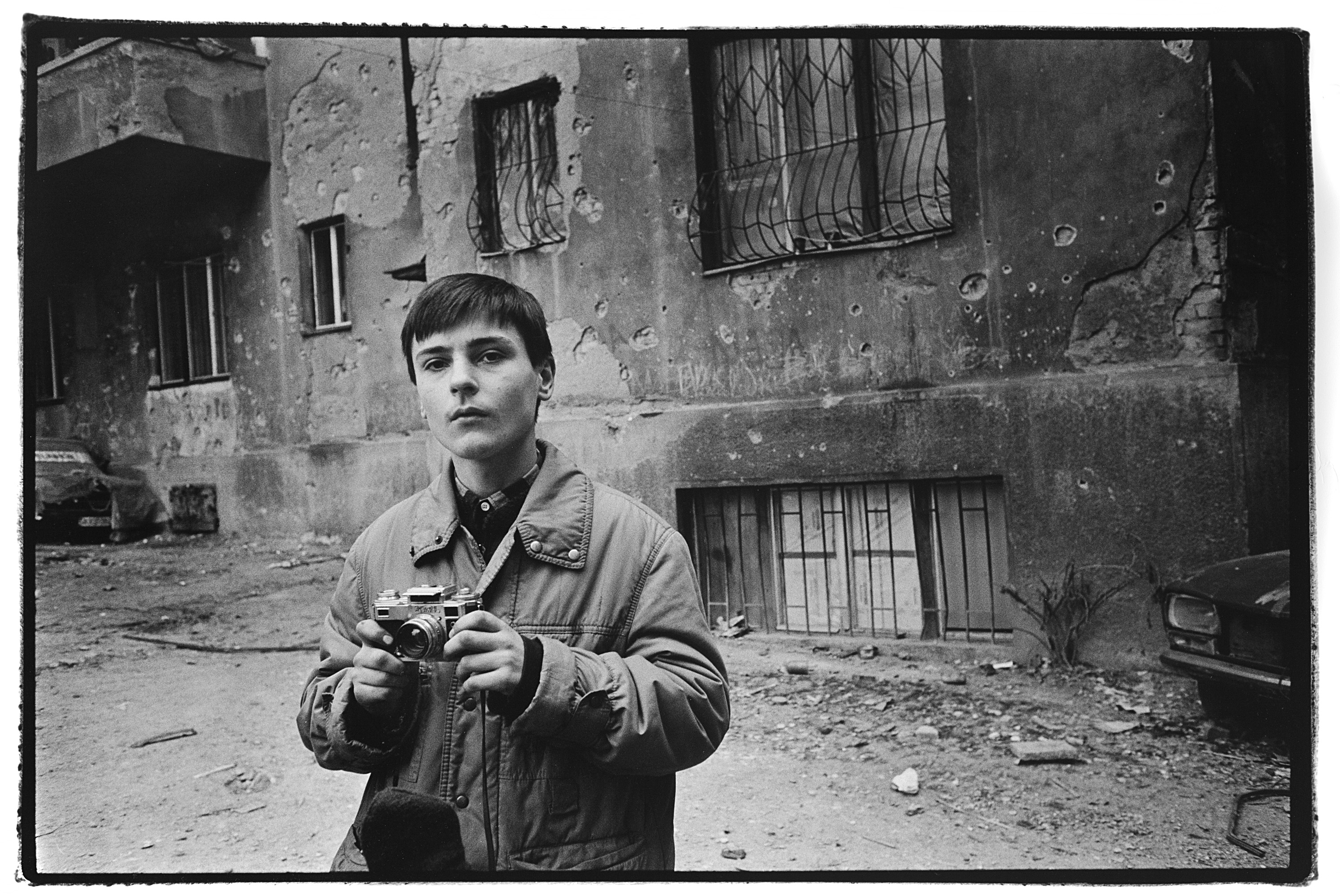

“Art stood for hope during and after the war”

After the outbreak of war in Bosnia 20 years ago, art helped some people cope with the reality, with theatre and concerts running throughout. Once the war ended, the Swiss also helped promote art as a beacon of hope.

“In the spring of 1992, no one believed that a real war had begun. When the first shots were fired, everyone thought that it would just last ten days,” said Almir Surkovic, a Bosnian artist who later moved to Switzerland.

Surkovic was 25 when the war broke out in his city of Sarajevo. At the time, he was a student at the Academy of Fine Arts.

In the beginning of the war, many artists from Bosnia and Herzegovina and abroad came to the ethnically diverse city of Sarajevo, which was the capital of culture in former Yugoslavia. Through words, images and music, they protested against war and violence. “There was a lot of hope and enthusiasm. I call it the romantic phase,” he told swissinfo.ch.

The conflict, however, did not last a few days. It went on for almost four years. More than 100,000 people died and more than two million others fled their homes. In Sarajevo alone, more than 11,500 people perished during the 44-month-long siege.

“During the first months, we thought that it would end soon, but as time passed, all of our hope disappeared into darkness. As of the winter, it was a real war, an unthinkable tragedy,” said Surkovic. Once, during the winter of 1993, the number of lights in Sarajevo could be counted on two hands. “There were six. Can you imagine? It was completely black.”

Searching for meaning

At the time, Surkovic was living with his parents and two brothers in an area of Sarajevo that he describes as a “multicultural proletarian mix”. The way to the academy, where classes were still held occasionally, was very dangerous because of snipers. Surkovic would rarely take the bus or tram.

“We would meet up with other artists there. When I was painting, I would ask myself, ‘What are you doing here? You’re risking your life to draw and paint.’”

Surkovic describes daily life in the besieged city as somewhere between a nightmare and a horror film. “Sometimes I would queue for 12 hours for ten litres of water. A lot of people lost their lives fetching water.”

The young painter found it particularly painful when trust between friends began to disintegrate. “I grew up in a multi-religious society. I didn’t even notice; it wasn’t important to me. And then, all of a sudden, we were Serb, Croatian, or Bosnian.”

When the attacks on Sarajevo had stopped, it seemed as if all hope had gone. “Everything that was constructive was gone. Everything that was civilised had disappeared.”

Recycled art

For the city’s artists, art played an important role then. “It took us far away from the war, brought us into another world and helped us to forget reality.”

Even at the worst moments, cultural life did not stop in Sarajevo. Exhibitions and concerts were held in basements. There was even a ‘war theatre’, which continued putting on shows for years.

City ruins also gave way to ‘recycled art’. Sculptors used charred wooden beams from roofs or broken glass from the bombings.

“It was very depressing and, for me, too closely linked to the war,” said Surkovic. Instead, he preferred to paint copies of masterpieces by Salvador Dali or Rubens.

Swiss support

After the war ended, part of the Swiss funding earmarked for rebuilding Bosnia went toward cultural collaboration. Wolfgang Amadeus Brülhart, who was cultural attaché at the Swiss embassy in Sarajevo from 1996-1998, told swissinfo.ch: “After the war, a lot of artists – painters, writers, directors – yearned for culture. Art stood for hope during and after the war.”

Brülhart, who now heads the Middle East and North Africa Political Department in Bern, is convinced that after a war people long to get back to normal. And that means going to the theatre, the movies and art exhibitions. “It helps to restore routine,” he said.

For that reason, he opened an atelier in his residence in Sarajevo where artists who no longer had a space to work could finally do so in peace. He also organised exhibitions, concerts and theatre shows. Soon, he became known in the local culture scene as ‘Amadeus of Sarajevo’.

Brülhart also became an important partner of the Sarajevo Film Festival, which was created during the last year of the war. Funding by Swiss citizens made it possible to buy chairs for the open-air event. Today, the festival is well established and plays a key role at a regional and international level.

A divided society

Switzerland also supported artistic exchanges. That’s how in 1998 – three years after the end of the war – Surkovic and three other Bosnian artists were able to spend six weeks in the Berthoud Kulturfabrik in canton Bern. During one of his painting shows, Surkovic met and fell in love with a Swiss woman and has been living in Bern since 1999.

In 1998, Swiss Interior Minister Ruth Dreifuss travelled to Sarajevo for the opening of the Bosnian National Gallery, which was renovated with Swiss funding. During that time, Dreifuss, who was responsible for culture, emphasised that it was particularly important to develop a place for art and culture because “society is built with soul”.

The constitution of a Bosnian society has proved difficult in the state as defined by the Dayton Accords. The 1995 agreement set up two entities to create one federal Bosnian government: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with Sarajevo as its capital, and the Republic of Serbia, with Banja Luka as its capital. Today, a sense of culture representing the whole country is lacking and Bosnia does not have a minister of culture.

Another remedy

For Brülhart, who has also served as the Swiss ambassador to Abu Dhabi, culture was a way of bringing an end to lingering animosities. “At the same time, culture was used a tool before and during the war, dividing even artistic communities. After the war, it was difficult for art to been seen as a foundation of community once again.”

But there is still hope. Since the end of the war, Sarajevo’s Academy of Fine Arts has supported many artists. “The tradition of Sarajevo as the capital of culture is back. I can feel it when I go back for the film festival.”

Surkovic had the same observation, although he feels that the local culture scene is not as strong as it once was. But to solve the worst problems, there also needs to be a certain political will. “Art is a nice initiative and can help to heal wounds. But it can’t do anything in the face of nationalism. For artists, it’s frustrating.”

There is a strong cultural exchange between Switzerland and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Led by Pro Helvetia, the Swiss Cultural Programme for Western Balkans established a new regional office in Sarajevo in July 2008.

Switzerland made it possible to renovate the Bosnian National Gallery. Additionally, the country helped to establish the Sarajevo Film Festival and finances the Human Rights Award every year.

In collaboration with the Youth Initiative for Human Rights, Switzerland supports the participation of young activists in regional forums. This year, it will finance the participation of three classes from across Bosnia.

Following the war, Switzerland also financed public chess tournaments in Sarajevo and Banja Luka. The games continue to be popular events in both cities.

(Translated by Rachel Marusak Hermann)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.