Why Charlemagne’s legacy lives on in Zurich

The great emperor Charlemagne may have died 1,200 years ago, but his presence is still very strong for the people of Zurich. In fact, his statue looks down upon them from the Grossmünster church, which, according to legend, he founded after stumbling upon the graves of the city’s patron saints.

It is a cold winter’s morning and a crowd of visitors are staring up at Charlemagne’s statue, on the church´s south tower. He is seated, with a sword in his hand to represent justice and war, with a golden crown upon his head. He seems to be gazing out over Switzerland´s financial capital.

“In fact he’s looking at the Fraumünster church,” our guide tells us. “It’s to tell that church, which was founded by a king, that this church was founded by an emperor and is one better!”

We are actually looking at a copy, the original statue, from around 1491, can be seen in the crypt. And this is not the only representation of the emperor. Inside, prominent on the plain walls of the Zwingli-Reformation influenced interior, is a relief, showing Charlemagne with the Zurich saints Felix and Regula.

More

Charlemagne’s Europe

Headless saints

“The saints had a strong influence on the religious life of the city in Zurich, they were martyrs who died for the Christian beliefs under Roman rule,” explains city archaeologist Andreas Motschi.

Having refused to worship Roman Gods, they were put on trial, tortured and then beheaded. “And then this miracle happened, the headless bodies got up, took their heads under their arms and walked a few steps to the place where they wanted to be buried. And this is the site of the Grossmünster,” Motschi says.

Charlemagne (748-814) is said to have rediscovered the graves of Felix and Regula after they had almost fallen into obscurity. Legend has it that, while out hunting in Germany, he came across a big stag, which he followed through all of Europe to Zurich.

The stag fell to its knees at the site of the graves, as did Charlemagne’s horse and his hunting dogs. Taking this as a sign from God, the emperor ordered a church to be built.

The cult which sprang up around Charlemagne survived the Reformation and is even celebrated to this day.

Zurich´s tailors’ guild (Zunft zur Schneidern) holds a Carlimahl every year on January 28, the anniversary of the emperor’s death.

Feast

Guild members meet for a dinner in modest surroundings at their guild building, a historic former mayor’s house, not far from the Grossmünster. At the end of the event, the guild master toasts Charlemagne, taking the first sip from the Carli goblet, which he then passes round.

“Charlemagne is said to have always had two tailors in his entourage, so that is why he is the patron of tailors in Zurich,” said the guild’s Jörg Zulauf.

“The event helps encourage and strengthen good fellowship, which is why the participants, invited by the guildmaster, say their motto ‘faithful and true forever!’ with a special sip from the cup,” Zulauf added.

There exists no portrait of Charlemagne from his lifetime – except on some coins, but this bears a profile in the Roman style.

Later idealised portraits increased the emperor’s legendary status. On show at the Swiss National Museum are paintings from two countries which like to claim Charlemagne as their own: an image created by Albrecht Dürer’s studio in Germany in 1514 and Louis-Félix Amiel’s depiction of 1839 from France.

Zurich symbol?

Charlemagne was a visionary ruler who did much to shape Europe. The church relief, which, unusually shows Felix and Regula with their heads on – most other images go for the more gruesome version – is a strong symbol, Motschi said.

“There is Charlemagne the worldly power, the emperor, the judge, the pious Christian, and both martyrs who have given the ultimate sacrifice for their Christian beliefs. This is very strong. Stronger than any bishop. The city was never a bishopric but it is well served with these three.”

Another story has Charlemagne – in the Haus zum Loch building, just outside the Grossmünster – acting as a judge for a snake whose eggs had been appropriated by a poisonous toad.

But it is not known whether Charlemagne really was the Grossmünster’s benefactor or whether he even came to Zurich, – even if he did visit other parts of Switzerland – as written sources from the time are scarce.

Indeed, the legends sprung up well after his death, and are for example chronicled by Heinrich Brennwald (1508-1516).

Charlemagne also pops up on the University of Zurich’s logo. And is not by chance that the Zurich-based Swiss National Museum is currently hosting a major exhibition on Charlemagne and Switzerland.

More

Charlemagne follows a deer to Zurich

The ‘great’

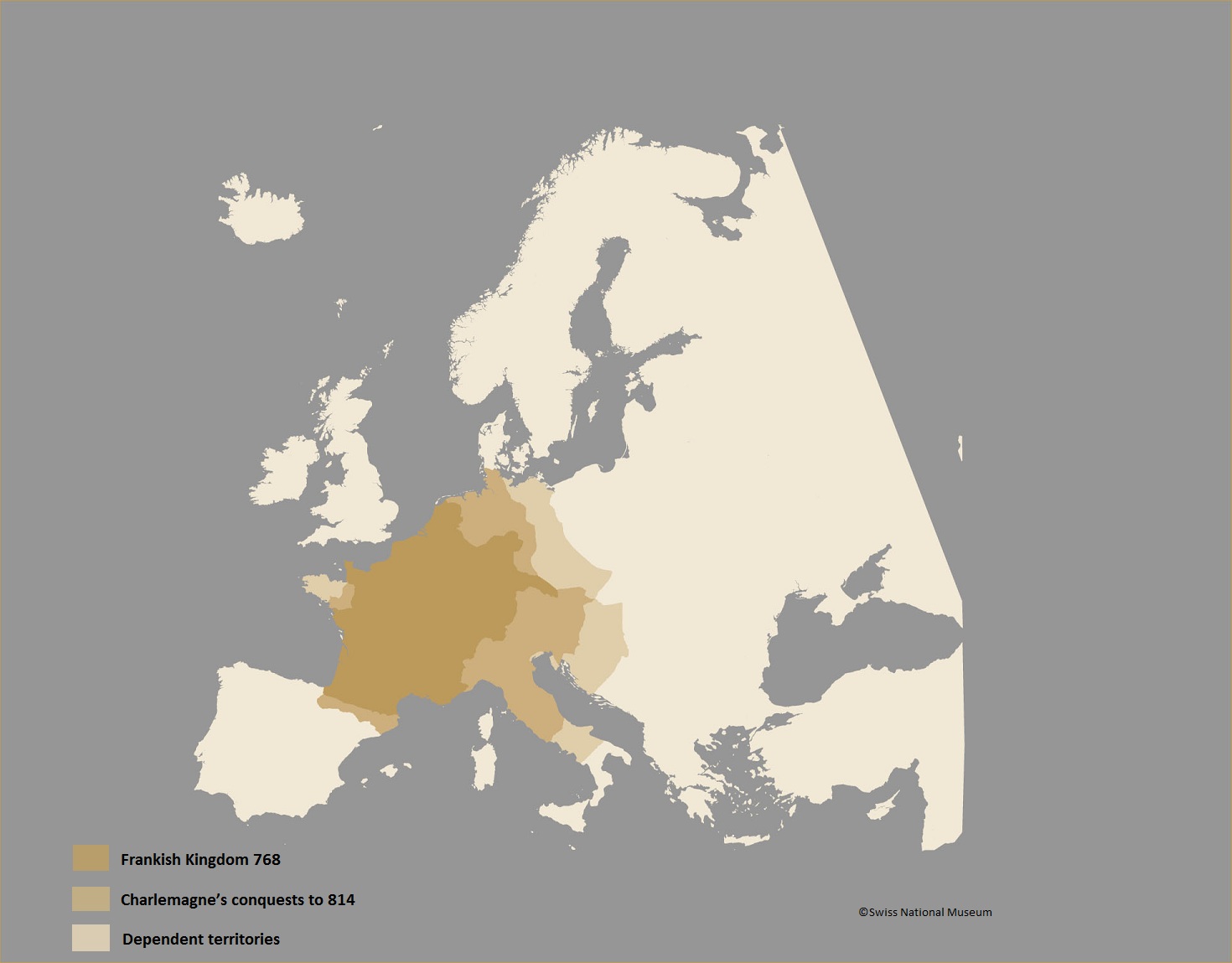

Crowned first emperor since the fall of Rome, Charlemagne unified Greater Europe and reformed the education system and society. What is now Switzerland lay at the heart of his empire, which covered almost half of Europe (see graphic).

Tall, the charismatic ruler, who was said to have a penetrating gaze, was already known as “great” during his lifetime.

As well as his writing and currency reforms, he introduced organisational structures but also sanctioned state violence to achieve his aims, said Jürg Goll, co-author of The Times of Charlemagne in Switzerland, and collaborator on the National Museum exhibition.

“But there is also the promotion of culture, language and religion, the encouragement of abbeys and art, all things which are visible today, and, when you take a very close look, all belong to our cultural heritage.”

Even if the Zurich visit is unclear, Charlemagne is known to have travelled to Geneva and across some of the alpine passes, according to Christine Keller, curator of the National Museum’s Charlemagne and Switzerland exhibition, which is running until February 2, 2014.

He is also said to have founded the abbey of St John in canton Graubünden, a Unesco world heritage site which boasts well-preserved Carolingian wall paintings. The abbey of St Gallen, also a Unesco site, flourished during Charlemagne’s time and its book production was influenced by Carolingian book art.

And Charlemagne’s coinage reform – he introduced the first “euro” – was used in parts of Switzerland until the introduction of the Swiss franc in 1850.

The multimedia exhibition brings together around 200 exhibits, on loan from 48 national and international establishments.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.