Roger Federer: ‘You cannot be alone at the top’

In 25 years of interviewing athletes, I’ve learnt that they never ask you anything back. Roger Federer is the exception. In the van to his private jet, he bombards me with questions: how badly have the gilets jaunes smashed up Paris, where I live? Do I have children?

When he discovers I have twins (he has two sets, one female, one male), and that my mother, like his, came from northern Johannesburg, he grins with delight: “We could be like brothers.” He speaks near-perfect English, with some of the singsong rhythm of his native Swiss-German.

This morning we are flying his shared NetJets plane from Zurich to Madrid, where he’s playing a tournament. We take off almost vertically: private jets fly at over 40,000 feet, higher than commercial planes, and whizz through the thin and nearly traffic-free air.

Federer and I sit facing each other in soft beige leather armchairs. The stewardess unfolds a dining table between us. Our fellow passengers – two of Federer’s fitness coaches and a NetJets man – loll on a sofa at the back of the cabin. I feel as if I’m in a magazine advertisement for first-class life. My tablemate, despite a slightly bulbous nose, is as beautiful as a Roman god. With his long legs slung over each other, he looks perfectly at ease in his body. He smiles and makes eye contact with the confidence of a man accustomed to getting a good response from everybody he meets. Unlike many athletes, he doesn’t need an agent by his side to censor his speech.

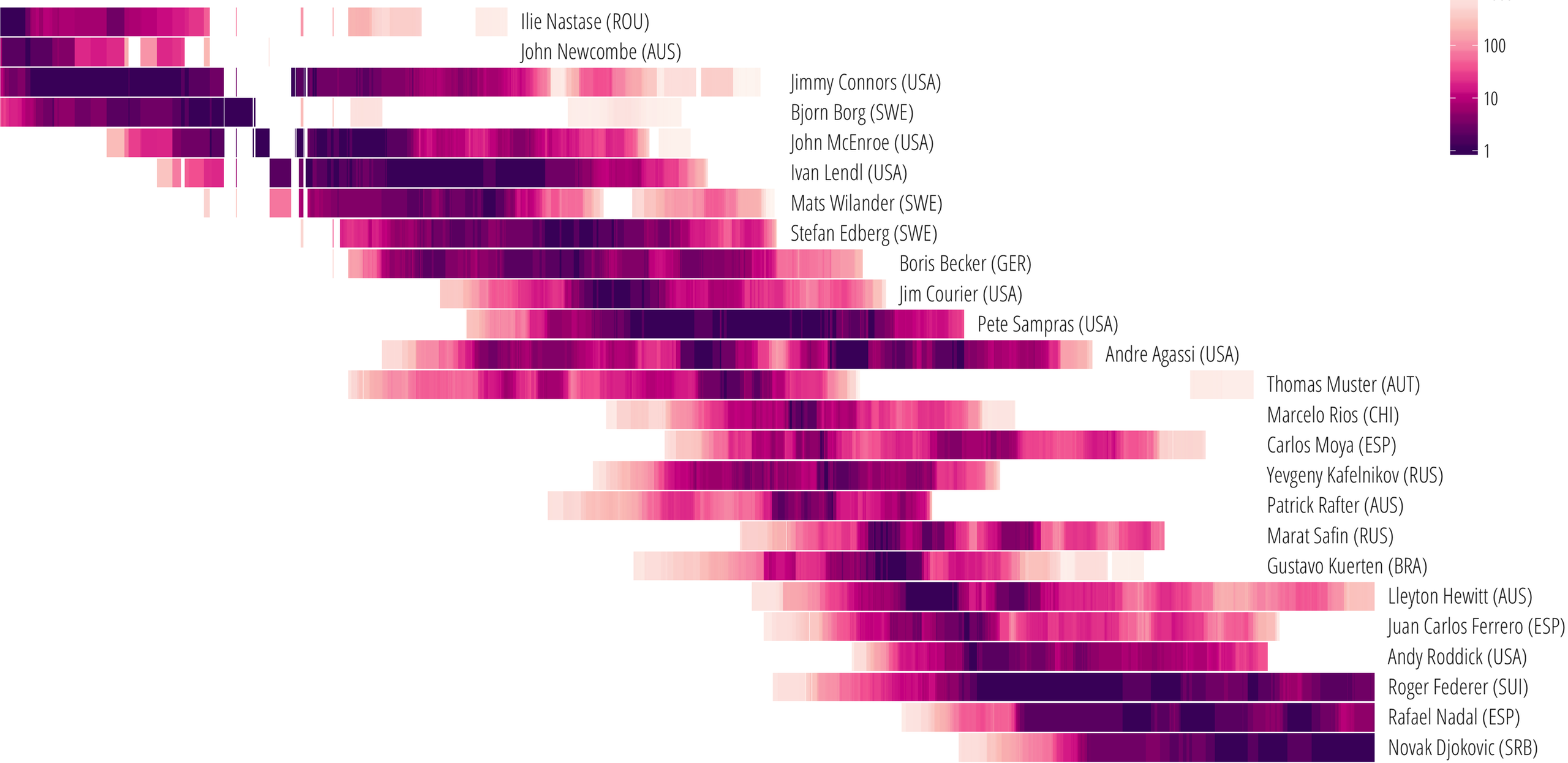

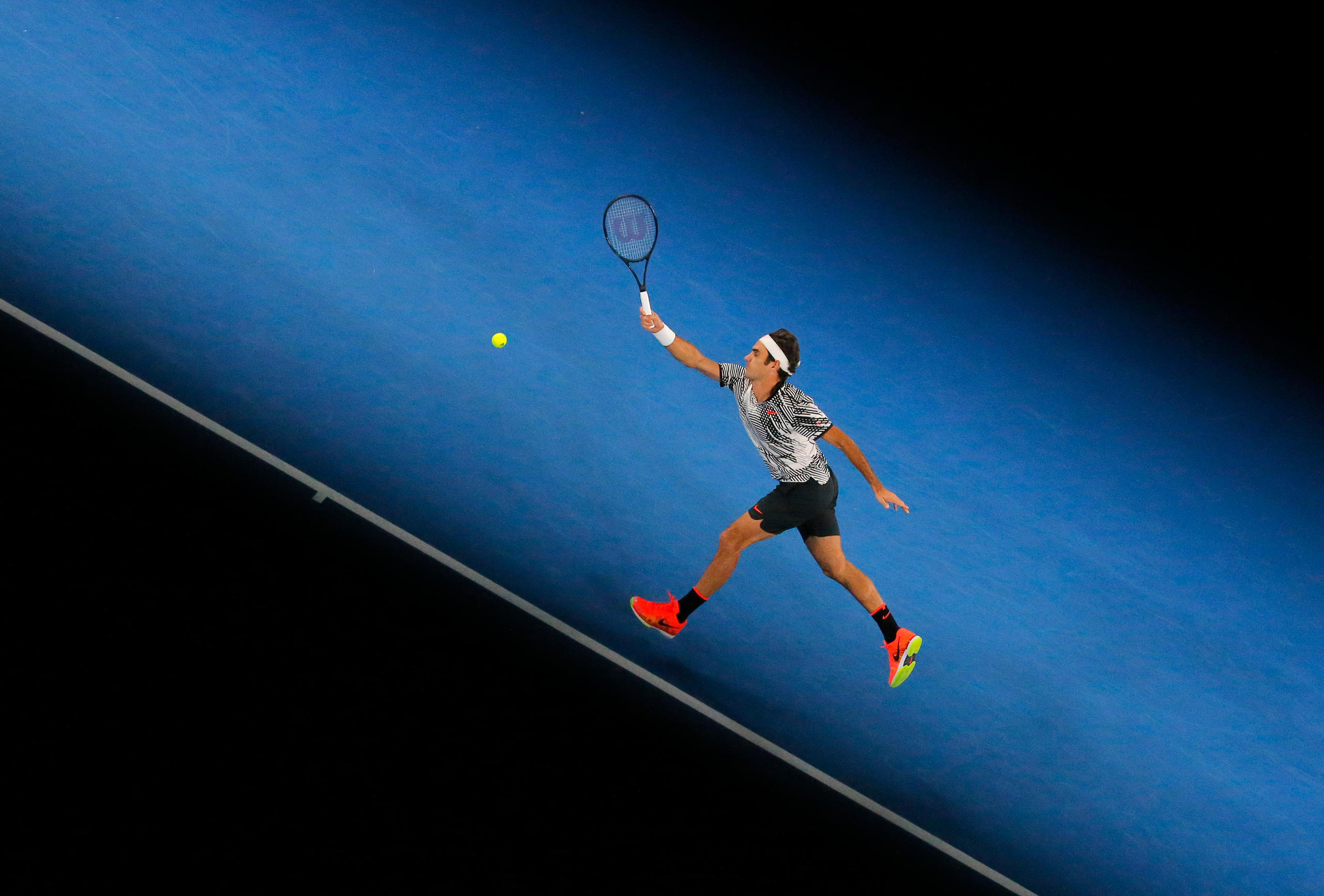

Aged 37, Federer has been on the circuit playing uniquely gorgeous tennis for 20 years. Pundits began predicting his retirement a decade ago, but he won another Wimbledon in 2017, the Australian Open last year (his 20th Grand Slam tournament) and he returns to Wimbledon next week ranking third in the world behind Novak Djokovic and Rafael Nadal, and seeded second by the tournament’s organisers. He is aiming for a record ninth victory. He seems genuinely unsure when he will retire. On the plane this morning, he appears as vigorous as a grown-up can be.

More

Who shows us how to live – Federer or Ronaldinho?

I want to get him to review his life and career. But first the stewardess brings us mini-croissants and fruit skewers. I had wondered whether Federer would eat human food; Djokovic likes his gluten-free and raw, when he deigns to eat at all. But Federer spreads marmalade on his croissant.

The stewardess suggests detox juices: “Morning energy!”

Federer smiles: “I never have, but let me try one.” She gives him three different juices. I order a café latte, he an espresso, and we both get muesli. This is turning out less Spartan than I’d feared.

“Really,” I start, “you’ve had multiple careers. You had your rise; then unchallenged supremacy; then rivals arrive…”

“I see it the same way,” he interrupts.

I continue: “Now you’re battling your way back to the top.”

Here he demurs. “It’s really the good times now. It’s like I’m on this tour, almost, and I can appreciate these moments. Not knowing what the end is, is also maybe nice.” He says he savours every trip now, because he knows it may be his last visit to that city.

Then how would he sum up his career?

“It’s gone way too fast. I feel like I was a junior yesterday.”

Biggest challenge

The bourgeois boy from Basel (his parents worked for the Ciba-Geigy pharmaceutical company) left home at 14 to enter a tennis academy. “I cried when I was away. Every time I took a train, Sunday night at six, I was as sad as could be, but it was my choice. You give up your childhood a bit, but I would probably do it all over again.”

At 15, he sat practising his autograph on paper tablecloths in French restaurants. “In case I got famous. I was thinking, ‘Hopefully one day I can win tournaments and be in the top 100. And who knows, maybe play against one of those guys I’ve seen on TV.’ I think at 18 I broke the top 100, and you’re like, ‘wow, I can really be on the tour. I’m in the locker room with Andre Agassi and Pete Sampras. My god, it’s so cool.’”

The teenager’s biggest challenge was off-court life: “Doing the red carpets, meeting important people, looking at women, speaking to women, speaking to people who I couldn’t place, it was hard. I was a shy person. But I think tennis helped me, really shaped me.”

Aged 19, at the Sydney Olympics, he met his future wife Mirka Vavrinec, who was playing tennis for Switzerland. Months later, he finally won a tournament. He recalls the carefree tennis of youth: “At 20, there’s a great point, and you’re like, ‘This one, I’m going to crush so hard, I’m actually going to make a hole into the ground.’ At 37 you’re like, ‘Hmm, I’m probably going to first hit it there, then manoeuvre the guy around, and somehow work my way to the net and finish off with a nice volley.’” Nowadays, he says, he sometimes has to push himself to try “the crazy shots”. He worries about becoming too canny, and tennis becoming too professional.

More

Record-breaking Federer returns to No. 1

He has wolfed down everything except his fruit. I initially assume our breakfast is over, but the stewardess reappears to take more orders.

“Could I maybe have one more espresso?” asks Federer, adding a very British, “Sorry.”

She suggests an omelette.

“Why not?” says Federer. I concur, and remark on his appetite.

“I don’t want to become too serious,” he says. “It also reminds me, maybe, I’m more than just a tennis player.” Has he really eaten KitKats before major finals? “I’ll have a coffee before every match, and if there is a chocolate on the side, I’ll have a chocolate. Or a cookie.” Geniuses don’t have to sacrifice like mortals.

But Federer had to learn to control his genius. I ask if he recognises parallels with another natural: Lionel Messi. Federer, a football fan, lights up. He asks excitedly if I’ve met Messi (he hasn’t). “Funny enough,” he says, “I haven’t spoken about Messi nearly enough. What I love about Messi probably most is when he gets the ball and is able to turn the body towards goal, and then he has full vision. Then he’s going to pass, or dribble, or shoot. There’s always three options for him. He’s one of the few who’s got that.”

I note the parallel: Federer, too, has many choices. The tennis writer and coach John Yandell once counted 20 variations of his forehand alone.

“Yes,” nods Federer. “The problem when you’re younger is knowing to use what when. That is quite – how do you say? – complex. Whereas if you’re a player who’s just very good at doing forehands and backhands across court all day, it’s easier.

“I’ve got a lot of different options. For us it’s more challenging. I think once you master the craft of knowing, ‘Which club shall I take out of the bag for this shot or pass?’, it’s incredibly exciting. Maybe this is why my love for the game is so big nowadays. Geometry, angles, when to hit which shot, should I serve and volley? Stay back? Should I chip and charge? Should I hit big?”

Fighting years

Once he mastered his options, he won his first Grand Slam tournament at Wimbledon in 2003. In January 2004 he added the Australian Open. Then, he said, “I took a conscious decision: I’d like to play for a long time.” His fitness coach recommended frequent breaks rather than chasing every appearance fee.

“You could just power out and say, ‘I’m planning to play till 30,’ like everybody else did, but I always thought it’d be so much fun to play through generations. Because our generations are not ten years, 15 years. Every five years you have somebody else. My generation, then Rafael, Novak and Andy [Murray]. Now you have the next generation. I wanted to experience that, and also – it sounds stupid now – maybe give younger guys an opportunity to play somebody old like me.”

From 2004 through January 2010 he towered over men’s tennis (except against Nadal on clay), winning 15 Grand Slam tournaments. In 2009 his twin daughters arrived. “For me, ’10 and ’11 are a blur, because of the children. All I remember is moments with my family, not my results. I’m happy it’s this way.”

But while Federer changed nappies, Nadal and Djokovic matured and began beating him on all surfaces. Nadal’s record against Federer, after a 15-year rivalry, stands at 24-15, after this month’s straight-set victory in the semi-finals of the French Open. Federer didn’t win any Grand Slam tournaments from 2013 through 2016. Given his age, most pundits assumed he was fading. He says, “Those were the fighting years for me. This is where I had to show battle.”

Would he have preferred unchallenged supremacy? “Of course. I would have loved to dominate forever. When Rafael and others were coming through, it took me some getting used to.” He says of Nadal: “At one point you tip your hat: you’re very good. I take joy after realising: you cannot just be alone at the top. You need rivals. I’m thankful to these guys, to make me a better player.”

Federer and Nadal have set a tone of niceness in the locker room. In the 1980s, Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe sometimes didn’t even speak to rivals and youngsters. Federer reports hearing that “in the ’80s and ’90s, a few guys really could not stand each other”.

By the time he started on tour, things had improved. “It was a very friendly locker room already, so I guess I just maintained that. Something I care deeply about is that young guys are welcomed nicely on to the tour, and they realise, ‘This is going to be fun, buddy, and, we, the top guys, are cool.’”

So when a teenage rookie walks into the locker room, Federer goes up and says hi?

“Yes. Then maybe: ‘You want to practise?’ And in that practice, you can chat: ‘What’s going on? Do you have brothers or sisters? Who was your hero growing up?’”

I interject: “But you were their hero.”

“Not always. Sometimes. That’s always awkward, especially when it happened the first time.”

In 2014, Federer’s sons were born. I quote the chess player Garry Kasparov, who told me over an FT Lunch in 2003 that at 40, “You can’t throw energy of nuclear size in the game. Because you have family, or kids, maybe businesses, you have other problems.”

Federer enthusiastically interrupts: “I always feel like I’m wearing two watches, one on myself and one of the family, because I know their schedules inside out. I know when they’re going to bed, when I’m at the tennis. I know I can quickly FaceTime them before they go to bed, 45 minutes before I play.

“I come back [home] after winning a match or tournament, or losing, and they’re like, ‘Hey, can you play Lego with me?’, and I’m like, ‘Let’s do it.’ Fine, I sometimes sit there and my match is going through my mind, but I am trying to give full attention to my son. I never saw in my vision, as a little boy, winning Wimbledon and then going to play with my children. So this is quite surreal.”

More

What family means to Roger Federer

His egalitarian fellow-Swiss allow him to be a regular dad. “I can go to playgrounds with my kids. It’s just me speaking to other parents, like what you would be doing.”

Don’t some parents want selfies?

“Yes, and that is normal. I have to make a decision when I walk out in the morning: am I in the mood for it? If not, well, I have a choice to stay home. And I can always be polite and say, ‘I’m with my children right now. I’m trying to build a house in the forest or whatever, but I’m happy to do it later.’”

What next?

After his knee operation in 2016, many predicted retirement. But he has since added three more Grand Slam titles. “I believe I’m at the height of my physical possibilities still,” he says. Though he takes more breaks nowadays, it’s not only to protect ageing bones. “You don’t want to go through a career racing through everything, and think, ‘I was never enjoying my biggest moments.’” A while back, he suggested to his wife that they take time to savour his tournament wins. Instead of flying out at once, “Maybe we could leave the next morning. We could have a nice dinner, a glass of champagne, chill out.”

Has he had a happy 20 years on tour? “Very.”

Does he fear the void afterwards? “Not really. Having a foundation, having four children, having some sponsors that are going to exceed my playing days, I think it will be fine.” And he won’t miss the stress, he adds.

“I will miss that other family: the players. I think that’s what will be toughest. One day, when you really leave, the question is, who are you still going to be in touch with? That’s when you realise who your real friends are from the tour. You realise there’s not many.”

Who are they? His immediate answer is touching: “I would think that I’m still in touch with Rafael.”

After nearly two hours of almost ceaseless conversation, we’re descending into Madrid. Federer gestures at the arid fields below us. “Europe is so much fun. You see, we’re travelling just a little bit. The landscape’s already semi-burnt from the sun. In Switzerland, everything’s just green. I love that about Europe.” He tries to enjoy the cities he visits. He never wanted his travels to be “hotel, club, airport, see you later. We try to have a hotel in the city centre, so we can go for a walk or go to a park. Nowadays, with the zoo, we see cities from a totally different angle with the kids. I like restaurants at night, to decompress with my wife and friends.”

Federer claims to enjoy interviews. I ask what we journalists still don’t get about him. That he’s a jokester in private, he replies. And also: “Maybe they don’t know I have a wine cellar, and I like to open a bottle with friends.”

On the tarmac, the NetJets man snaps our picture. Federer throws an arm around me, and I put my hand on his back. Every other back I’ve touched felt like a single undefined mass. On Federer’s back you feel every bone and muscle. It’s like reading an anatomy textbook in Braille.

Then I go to the regular terminal for my economy flight home.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2019

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.