Gurlitt collection bequeathed to Bern museum

Bern’s Kunstmuseum has announced that it has been named sole heir to the controversial art collection in the possession of Cornelius Gurlitt, who died on Tuesday aged 81. The news has come “like a bolt from the blue”, the museum said.

The Museum of Fine Arts will not only inherit works of modern masters, such as Picasso, Chagall and Matisse, but may also face restitution claims from the heirs of Nazi-era Jewish collectors.

Speaking to Swiss public radio, the president of the Kunstmuseum’s board said the museum had had no contact yet with the German authorities. “We don’t know yet what obligations will be passed on to us,” Christoph Schäublin said.

Gurlitt, who lived a reclusive lifestyle, inherited the paintings, sketches and prints from his father Hildebrand Gurlitt, a prominent German art dealer in the 1930s and 1940s. The current value of the collection is an estimated CHF1.23 billion ($1.4 billion).

The secret hoard of more than 1,400 artworks was discovered by chance in 2012 when German tax officials raided Gurlitt’s Munich apartment. The collection was thought to have been lost in the Second World War.

The officials were looking for possible undeclared income after Gurlitt, returning from Switzerland by train, had been found by customs officers to be carrying a large sum of cash.

More

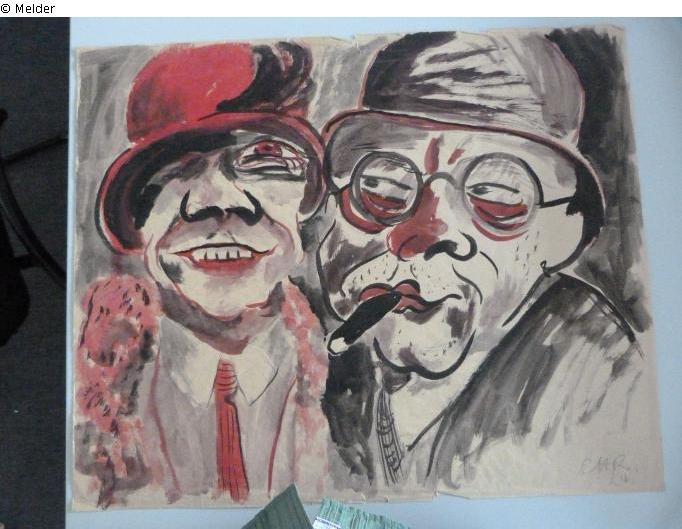

Inside the Gurlitt collection

Complications

Gurlitt’s desire to bequeath the collection to an art institute outside Germany did not come as a surprise. He was outraged by his treatment at the hands of the authorities in Munich and had trouble dealing with the media attention his unique story generated.

Despite the speculation, the Kunstmuseum in Bern was taken aback when contacted by Gurlitt’s lawyer. Schäublin said he never dreamed the paintings would be passed on to them.

“All the more so because there were no links whatsoever between Mr Gurlitt and the Kunstmuseum Bern,” he said.

Asked why he thought Gurlitt had chosen the Bern museum, Schäublin said the fact that it is run by a private foundation may have played a role, as this detail was mentioned in Gurlitt’s will.

In a statement, the museum’s board said they were “surprised and delighted” by the bequest.

“But at the same time [we] do not wish to conceal the fact that this magnificent bequest brings with it a considerable burden of responsibility and a wealth of questions of the most difficult and sensitive kind, and questions in particular of a legal and ethical nature.”

According to German officials, any heirs are bound by a deal under which Gurlitt agreed that hundreds of pieces from the collection would remain in government hands while they are checked for a possible Nazi-era past.

More

Swiss urged to provide missing links to Nazi-looted art

Looted art?

As a major hub for the sale and transfer of Nazi-looted art during the Second World War, Switzerland is said to hold the key to provenance gaps for works that may have been stolen in Nazi-occupied Europe during those years.

The Swiss Federal Office of Culture launched an online portal last year in an effort to help claimants, museums and researchers coordinate their efforts in the identification of ‘spoliated’ art (works seized by force).

Hildebrand Gurlitt was a respected art historian who may have felt the need to ingratiate himself to the Nazis, in part because he was Jewish on his mother’s side.

As a regime-authorised dealer, he acquired the collection of modernist masterpieces either through duress, by buying them for a pittance from Jewish families fleeing the country, or obtaining them through the confiscation process set up by the Nazis to eliminate contemporary “degenerate” art from Germany.

Provenance research can best be described as the putting together of a puzzle. But in the case of art that changed hands before and during the last war, so many pieces of the puzzle have gone missing, or were never there in the first place. And conjectures, on which many restitutions claims are made for want of satisfactory documentation, are not admitted in courts of law.

“One of the greatest difficulties in provenance research is the identification of a work of art in the first place,” warns international art expert, Janet Briner, who is also an active board member of the Swiss Institute for Art Research.

She told swissinfo.ch that over decades important information gets lost: inventory labels get torn or fall off, paintings get relined – with all the valuable facts, such as titles, dates and places of exhibitions disappearing from the back of the canvas, frames are changed.

Provenance research is not always done in the best conditions either. “When a collector passes away, fiscal authorities can require an inventory in short time, which does not always allow for the proper research to be done, including when a collection passes from one generation to the next.”

“Due diligence, under time pressure to determine the provenance of each work of art in a large collection becomes costly and difficult, if not impossible,” she said.

Considering that the Bavarian authorities only put one art historian on the Gurlitt case when the 1,400 artworks were found, the estimated time for her to do the job would have been several years, if not several decades.

Hans-Peter Keller, the head of Swiss art for Christie’s auction house is both more optimistic and more cautious. He informed swissinfo.ch that provenance research always starts with what the vendor has to say and an auction house’s due diligence is first to check that the work of art is genuine and has not been stolen at any point in time.

The question of how Gurlitt was able to sell off pieces of his collection therefore remains.

Were Gurlitt’s will considered valid and were Kunstmuseum Bern to accept the gift, it will be battling between two moral obligations: the one spelled out by the Washington Principles signed by 44 nations in 1998 to promote the identification and restitution of Nazi-spoliated art and the belief held by many museums today that it is their duty to allow access to great art that would otherwise be cloistered in individual collections.

(Michèle Laird, swissinfo.ch)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.