How contemporary Chinese art mirrors change

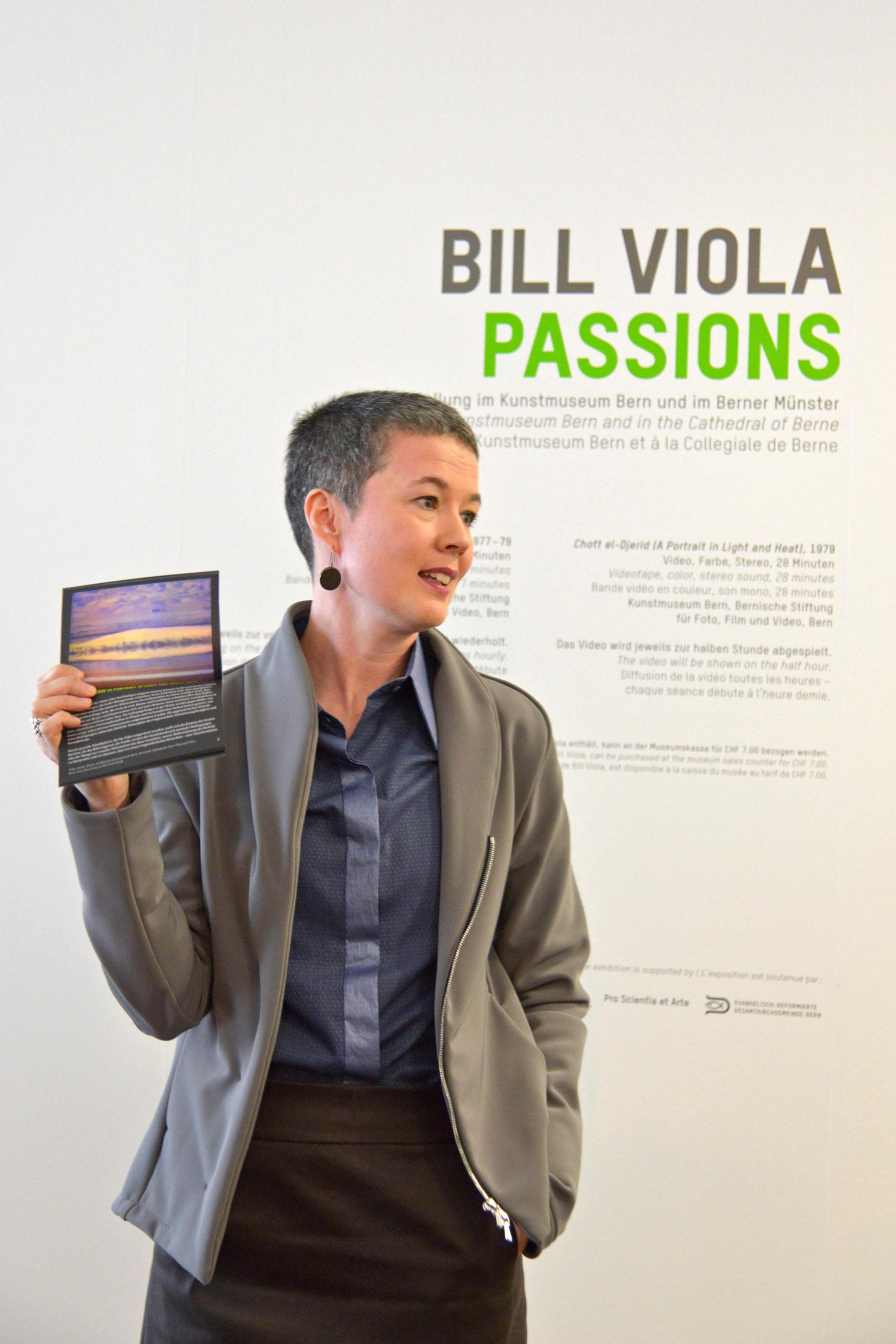

New wealth, mobility, consumerism, spiritual emptiness, and the loneliness of only children are leaving their mark on Chinese art. At Bern’s Zentrum Paul Klee and Museum of Fine Arts, works by Chinese artists like Ai Weiwei and Zhuang Hui provide insight into the world of China in an exhibition called “Chinese Whispers”.

“Chinese Whispers,” “Telephone,” or “Whisper Down the Lane” is the name of a game in which children sit in a circle and pass on a message by whispering it from one to the next. The fun of the game is that the original message is increasingly distorted from the first to the last message.

As an educational exercise, the game shows how rumours and misunderstandings can arise and makes clear how unreliable oral communication can be in general. It is therefore particularly appropriate as a metaphor for discussing contemporary Chinese art – art that is alien to us because of the cultural, historical and political differences, but also increasingly familiar, because the art market is so global and hungry for new forms of expression that contemporary Chinese art found its way to “the West” quite some time ago.

Since China first opened its economy under the reformist party leader Deng Xioping in 1978, the country has experienced cataclysmic change, unique in recent human history. With additional impetus from the “open door” policies of the 1990s, everything was modernised, entire cities like Beijing and Shanghai were redesigned, and people were mobilised into internal mass migrations.

Changing art world

The counterpoint to increasing wealth and better conditions in education, labour and health was the eradication of both communist and traditional China and the uprooting of families. Many artists focused their work on this brutal upheaval and on how the restrictive, one-party-state ideology conflicted with international openness and the impact of that tension on recent history. At the same time, Chinese art was influenced by the arrival of new media in the 1990s (video, photography, performance), the use of materials not usually employed in art (human or animal body parts), and new artistic ideas that were clustered under the term “experimental art”. Questions of identity moved onto centre stage, and political criticism was sometimes gilded in irony in the guise of “gaudy art”, or delivered with provocative directness in the form of “cynical realism” and “political pop”.

In the 2000s, art was far less radical and political, though some artists could gain capital in the West with the movements mentioned above – because this Chinese self-criticism confirmed the West in its presumption of ideological superiority. But the question of how to portray daily life and recent events remained in the 2000s. What are the central icons of a generation which has almost the same degree of access to the internet and information as the West, and which can also travel without major restrictions?

More

Contemporary Chinese art makes a noise in Bern

Since the oft-pronounced end of (western) art history, discussions are taking place worldwide about global art. Against the backdrop of various historical events, this art should be free from western dictates, open to all international art traditions, and contribute to a history of the exchange of ideas rather than to a history of the influence of the West on non-western positions.

Role of traditional art

Against the backdrop of globalisation – which has also penetrated the art market – and the fear of an assimilation of worldwide art created to meet commercial western standards that would lead to a selling-out of individual cultural legacies, artistic engagement with regional or national art traditions has gained new significance. In western cultures, engagement with tradition often takes the postmodern form of an ironic quotation, or a sophisticated retro allusion. In an Asian context, the authenticity of national artistic creation can emerge as a means of self-assertion towards the West, or as an expression of conservative social tendencies.

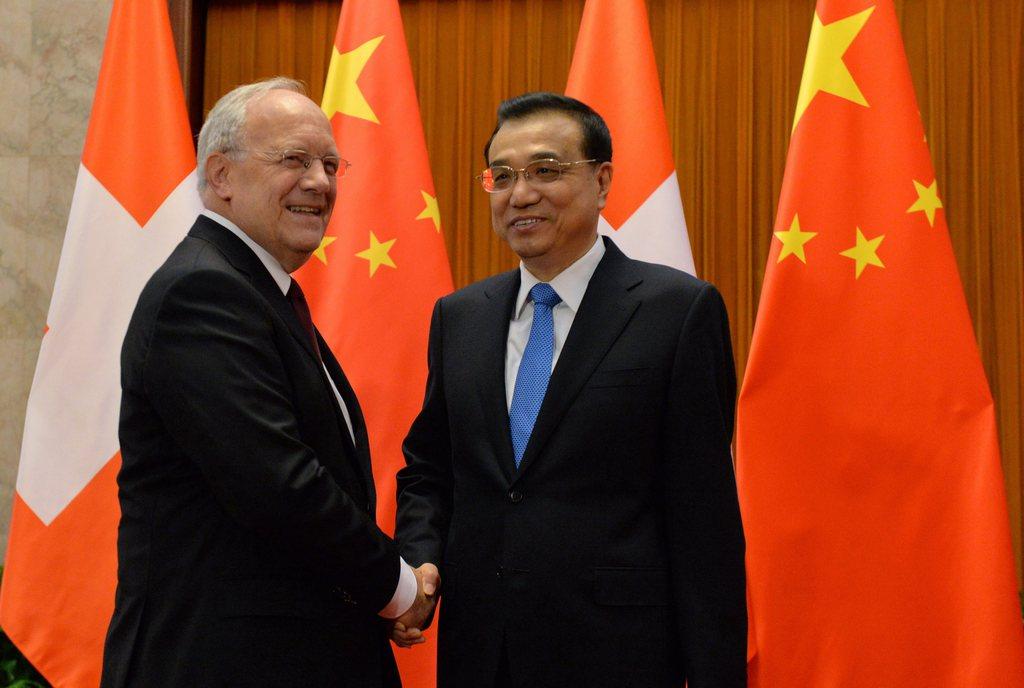

The major transformation that China has undergone since 1978, catapulting its society from communism to capitalism, was repeatedly designated the “Chinese Dream” by the People’s Party after 2012. The ruling general secretary, Xi Jinping, declared the official party goals to be “national rejuvenation, improvement of living conditions, wealth, building a better society and strengthening the military” and called on young people in particular to “dream, work hard to realise the dreams and to thereby contribute to the revitalisation of the nation.” The party secretary was clearly trying to contain the threat of a loss of integrity and of faith in the government caused by rampant corruption in China. Hardly a day passes without nationwide reports of some scandal involving corruption, bribery, food, or abuse of office.

Social values such as Confucius-inspired modesty, peaceful harmony and considering the common good have been thrown overboard with the introduction of capitalism. Instead, the desire for money dominates – for expensive watches and big cars. The result is a spiritual vacuum for many Chinese, although love for the fellow man still ranks highly, at least as far as families and close friends are concerned. But beyond that, everyone thinks only about his own gain and constantly suspects others of trying to cheat him. In this climate of social detachment and declining trustworthiness, many Chinese are turning to religion. The new wealth, the obsession with consumption, the spiritual vacuum, and the loneliness of only children – combined with new mobility and self-determination – are also leaving their mark on art.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of swissinfo.ch.

Opinion series

swissinfo.ch publishes op-ed articles by contributors writing on a wide range of topics – Swiss issues or those that impact Switzerland. The selection of articles presents a diversity of opinions designed to enrich the debate on the issues discussed.

Translated from German by Catherine Hickley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.