What’s the real risk from avalanches?

On Thursday, an avalanche crashed spectacularly into a hotel restaurant at a small mountain resort in eastern Switzerland. Three people received minor injuries. What are the avalanche risks in Switzerland and how are such hazards monitored?

At 4.30pm on Thursday, a 300 metre-wide avalanche swept down the Schwägalp in canton Appenzell Outer Rhodes burying over 25 vehicles in a car park and crashing into the restaurant of the Hotel SäntisExternal link. Search and rescue operations are continuing.

How common are avalanches in Switzerland?

Over the past 20 yearsExternal link, there has been an average of 100 reported avalanches a year where people were involved. On average, 23 people die in avalanches every year, the majority (+90%) in open mountainous areas where people were off-piste skiing, snowboarding, or backcountry touring on skis or snowshoes.

In controlled areas (roads, railways, communities and secured ski runs) the 15-year annual average number of victims dropped from 15 at the end of the 1940s to less than one in 2010. The last time anyone died in a building hit by an avalanche was in 1999.

Avalanches such as the one that hit the Hotel Säntis in Schwägalp are rare.

Bruno Vattioni, director of the Säntis lift company, said on Friday “an avalanche of this size is not predictable”. Locals have not experienced anything like it in the 84 years’ existence of the Säntis cable car. Normally, the southern face of the Säntis, the other side of the peak, is the more dangerous.

How are avalanches normally monitored?

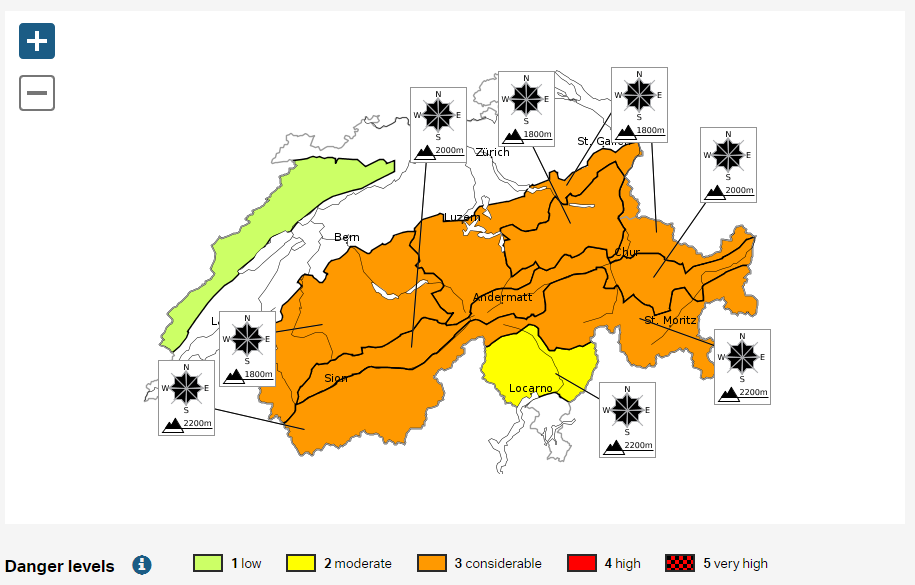

Since 1945, the national avalanche warning service, run by the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF) in DavosExternal link, produces a twice-daily national avalanche bulletinExternal link using data gathered by 200 people trained to do the job and 170 automatic measuring stations dotted across the Swiss Alps. This information is shared and used by the police, cantons, communes, mountain resorts, rescue services and other winter professionals across the country.

Are they normally successful at monitoring and protecting against avalanches?

The density of the avalanche warning network and the level of training and expertise is unique to Switzerland. But it cannot catch every avalanche, as SLF avalanche forecaster Frank Techel explained to swissinfo.ch.

“We have an extensive observer network that is spread evenly across the Alps and Jura mountains. But we only hear about a fraction of all avalanches. We can’t monitor every avalanche as sometimes there is poor visibility or heavy snowfall and they may go unnoticed if far from a populated area. We don’t have an observer in every valley,” he said.

Since the deadly avalanche winter of 1951, organised avalanche mitigation has improved dramatically. This led to the creation of avalanche bulletins, hazard mapping and mitigation projects. Defence structures, such as steel bridges and snow nets, sprouted up across the Swiss Alps above protection forests. Today, they stretch over 1,000 kilometres, protecting resorts and other locations.

Last November, Switzerland and Austria’s knowledge, experience and strategies of managing avalanche risks were officially recognised as a global cultural treasure by the United Nations and given coveted UNESCO intangible cultural heritage status.

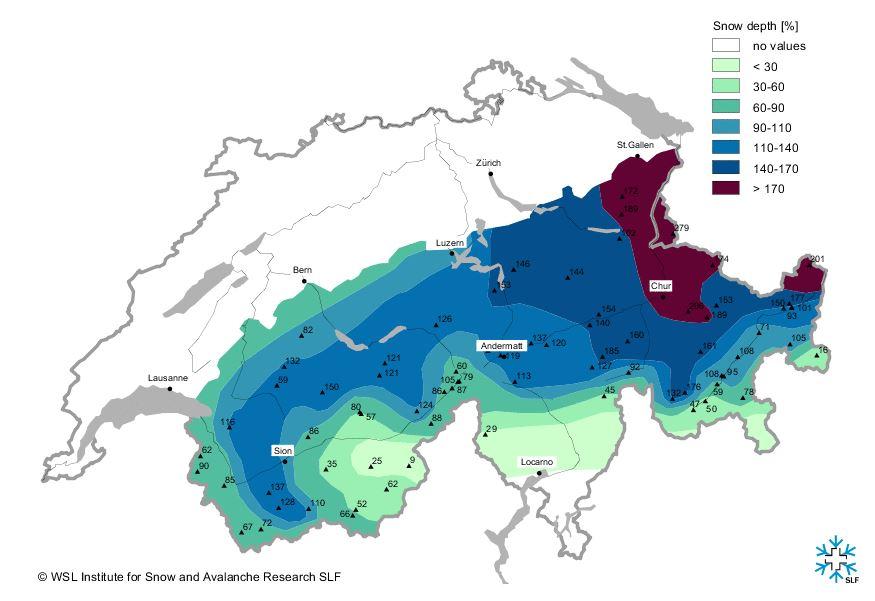

This SLF chart below shows the depth of snow on January 10, as a percentage of the long-term averages.

Are there any rules on where buildings can be built, as far as avalanches are concerned?

Hazard maps are used by the cantonal and communal authorities to define where avalanches frequently occur and safe building zones, and where additional protection measures are needed.

What happens if there is a high avalanche risk?

In affected regions, a local avalanche commission – which may comprise local officials, police officers, mountain guides and ski resort workers – typically meets to analyse SLF regional forecasts and other local weather data to assess the conditions and to decide upon appropriate action, which may involve closing ski areas, hiking trails, roads, buildings or evacuating residents and tourists.

How can people visiting the Alps take precautions, and do they even need to?

If visitors to the Alps are concerned about potential snow and avalanche risks, they should check with their tour operator, or local tourism office. Additional up-to-date information on avalanches and weather can be found at the following websites: SFLExternal link, SRF MeteoExternal link and MeteoSchweizExternal link.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.