Advantage Gstaad: 100 years of ‘unique’ tennis

As the balls fly at the Swiss Open Gstaad for the 100th time, swissinfo.ch looks back at the tournament’s highs (it’s played at 1,050 metres above sea level) and lows, its effect on local tourism and the surprising challenges involved in organising an international tennis competition in a small mountain village.

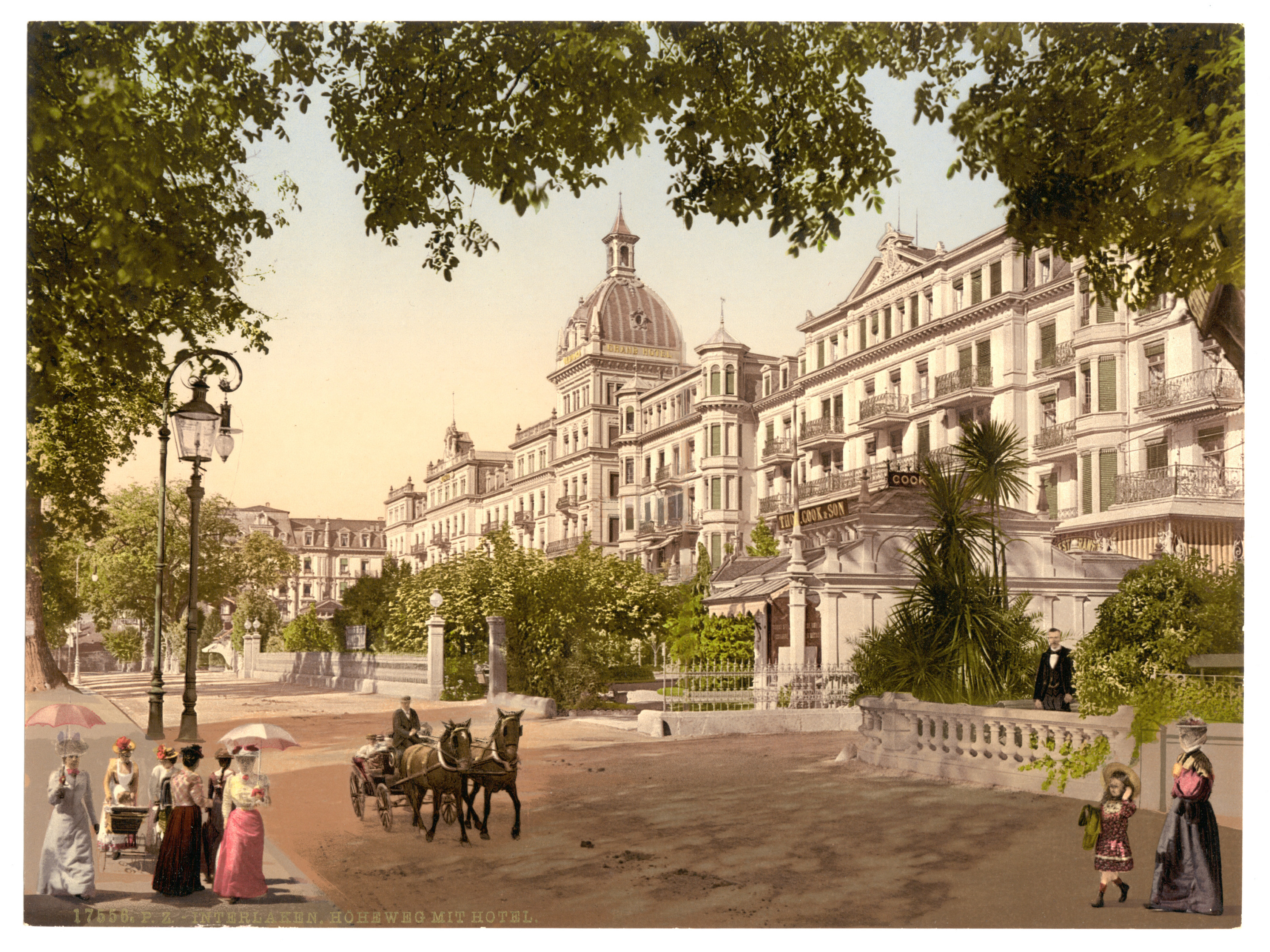

“The British are coming!” Swiss entrepreneurs would have cried at the beginning of the 20th century as railways crept up and through the Alps, laying the foundations for a landscape-changing tourism boom.

In December 1904, the Montreux-Oberland Bernois railway reached the idyllic village of Gstaad in the Bernese Oberland. Hotels couldn’t be built fast enough and in 1913 the iconic Gstaad Palace Hotel opened for business.

“We then had to entertain these tourists,” explained Julien Finkbeiner, vice-director of the Swiss Open Gstaad, which starts on Saturday. “As most of them were from England, it was natural to build three tennis courts next to the hotel, and this is where it all started.”

By all accounts, it was a wild success. “The tennis tournament in Gstaad enjoyed indescribable summer splendour on the beautiful Gstaad Palace courts on Saturday, the final day of play,” wrote the Anzeiger von Saanen. “In the evening, players and dance enthusiasts gathered in the great Winter Palace hall for a final ball.”

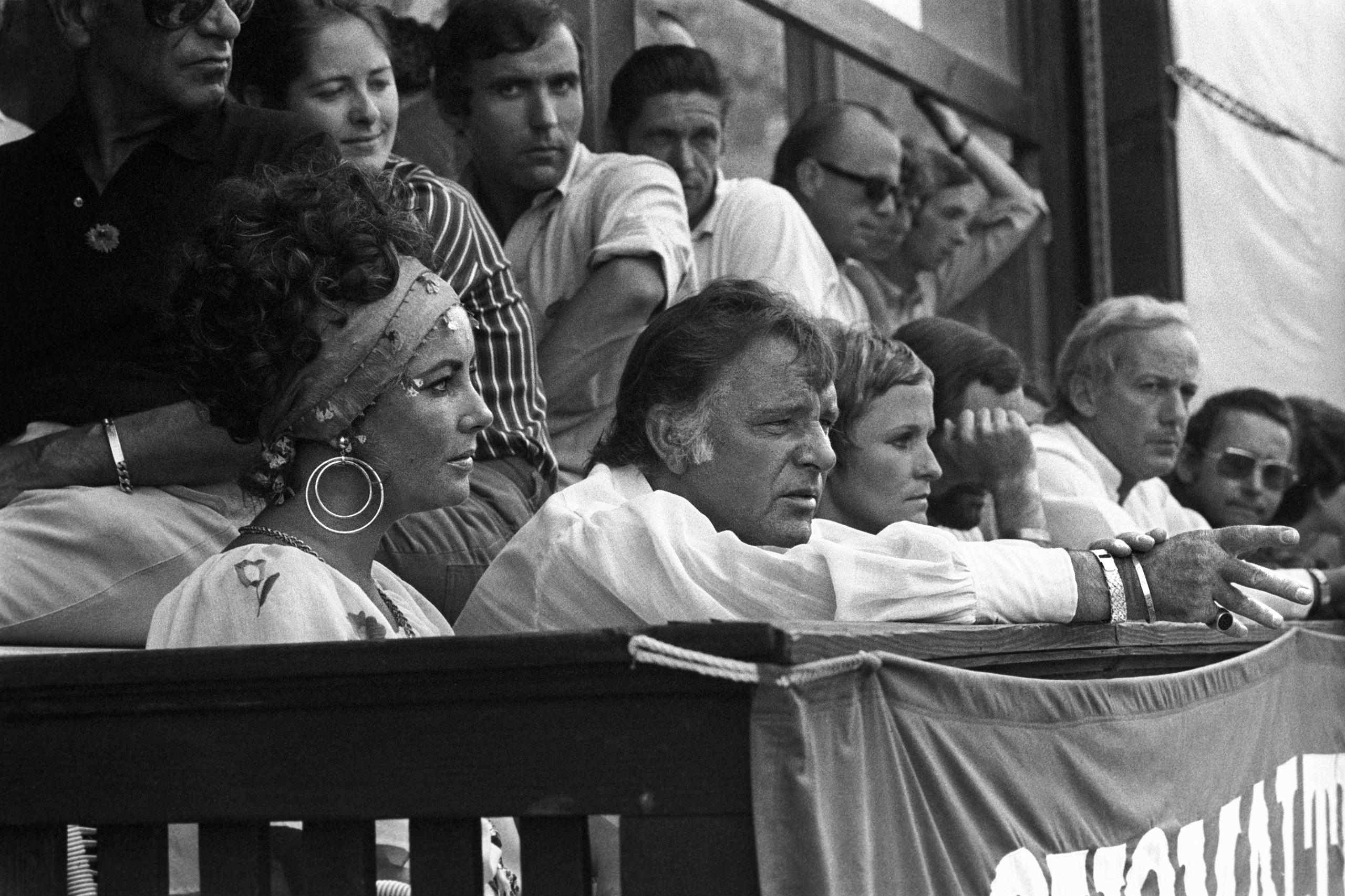

After the war, the village consolidated its reputation for elegance and exclusivity – it became a discreet playground for stars such as Bridget Bardot, Liz Taylor and Grace Kelly – and this in turn boosted the tournament’s reputation.

In 1966 a cocktail party held on the terrace of the Palace Hotel involved top Australian players Roy Emerson, Fred Stolle and John Newcombe as scantily clad tennis-playing cavemen, with female players dancing the can-can…

“Because it was not so easy to travel, most of the Australian players, who were some of the best in the world, used to go to England [for Wimbledon] and not return to Australia immediately. They would stay in Europe and play in Gstaad,” Finkbeiner told swissinfo.ch.

“Back then it was quite unusual for tennis players to stay in five-star hotels like the Palace.”

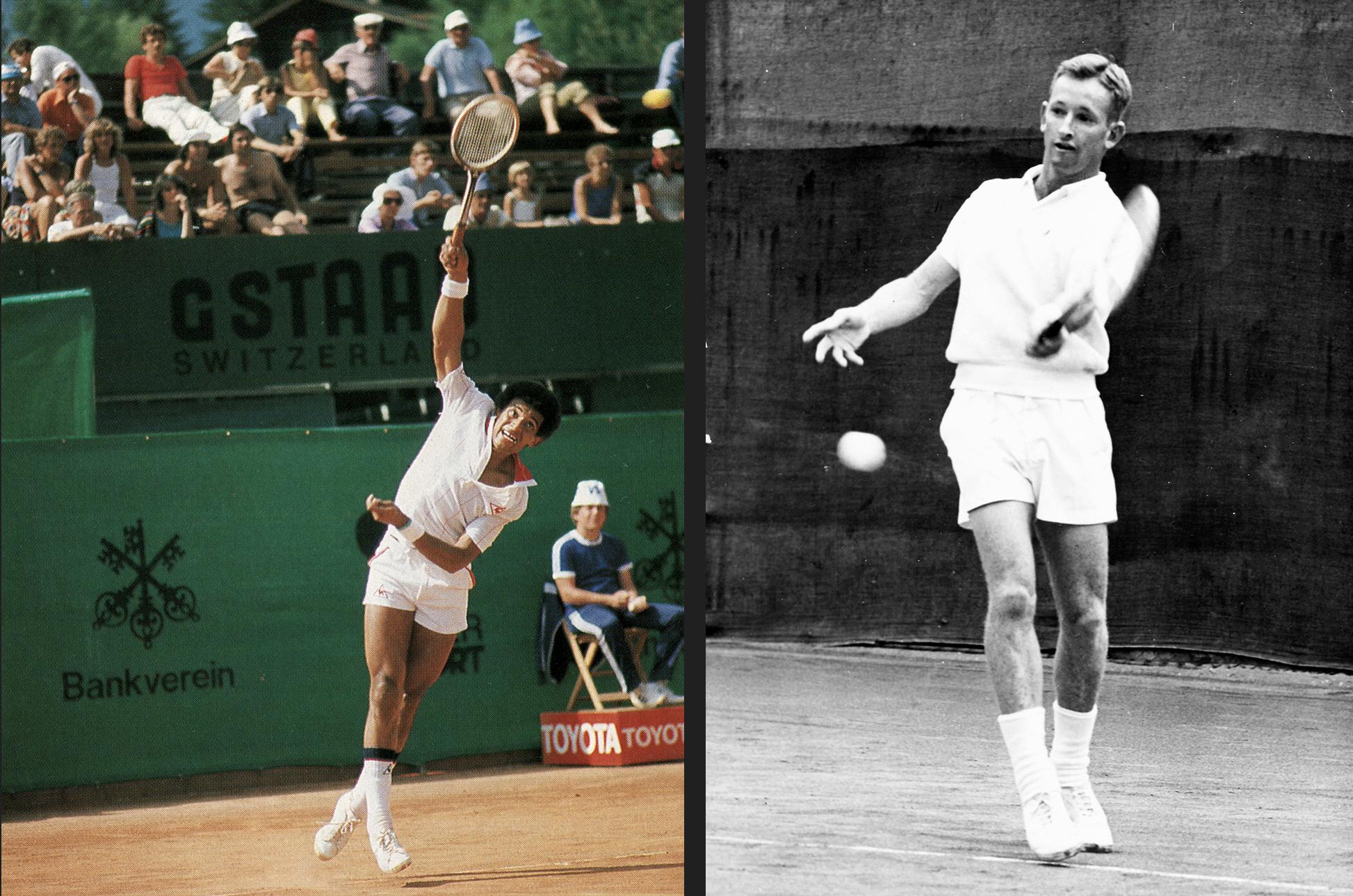

An additional attraction was the chance for revenge for defeats at Wimbledon, which has always been held a few weeks before Gstaad. Indeed the Swiss tournament is often referred to as the “Wimbledon of the Alps”, despite the surface being clay not grass.

“In 1958, the final in Wimbledon was the same as in Gstaad. It would be like having Djokovic and Federer meeting in the final in Gstaad!” Finkbeiner says wistfully.

However, the stunning scenery was not always enough to attract the big names. In 1954, for example, players’ travel expenses were covered and gold watches were awarded to winners.

The Open Era eventually dawned in 1968, with tournaments no longer limited to amateurs. Top players were now “offered” to organisers for a fee. Gone were the days at Gstaad when players would appear in return for board and lodging, with expenses not higher than CHF1,000 (about $2,000 at the time, $14,000 today).

The 100th Swiss Open Gstaad is taking place from July 25 to August 2.

Special events include a show match at 2.30pm on July 26 with big players from the past such as Ilie Nastase, Alex Corretja and Roy Emerson.

Top seed is Belgian David Goffin, ranked 14 in the world.

Total prize money is €439,405 (CHF458,000).

Altitude problem

At an altitude of 1,050 metres, the Swiss Open Gstaad is the highest ATP (Association of Tennis Professionals) tournament in Europe (the Ecuador Open held in Quito is the highest in the world at a breathtaking 2,850 metres).

“In terms of organisation, it’s not as if we face big challenges because it’s high. There could be snow, but touch wood we haven’t had snow in the past ten years,” Finkbeiner said.

“The biggest challenge was and is for players, because the balls fly higher and furtherExternal link. Twenty years ago it was a bigger challenge because of the material [different ball types were introduced in 2002]. Back then we used to receive the balls two or three months before the tournament and we would have to open all the boxes so the pressure inside the ball would be exactly the same as that outside the ball. That was a trick to soften the ball.”

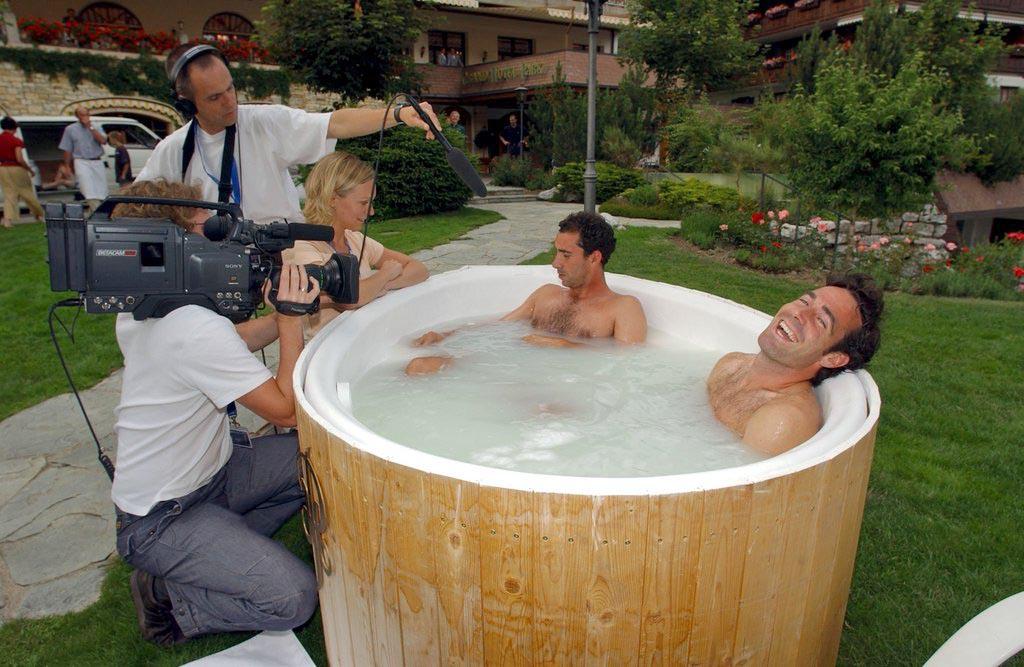

If you walk through Gstaad during tennis week, you will be struck – not by stray balls – but by the village-fête atmosphere.

As Finkbeiner says, “it’s not a city tournament like in Basel or Geneva. It’s like going on holiday. A sunny day in July in Gstaad is one of the most beautiful settings in the world”.

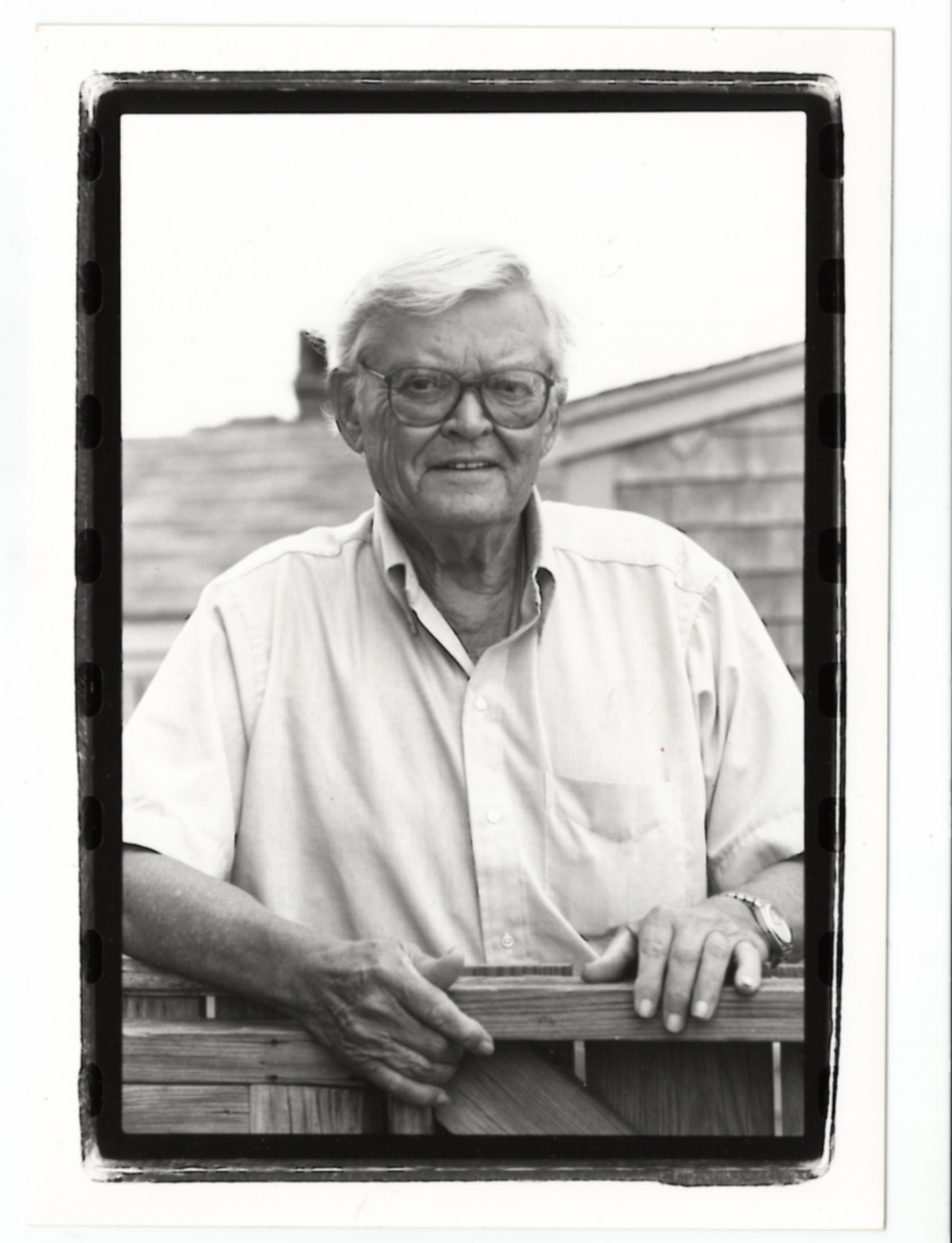

Tennis legend Roy Emerson agrees. “I could barely concentrate when I played here for the first time in the 1950s,” wrote the winner of a record five trophies at Gstaad.

“Why not? Because I could hardly believe how beautiful it all was: the mountains, the train that ran around the court and whistled when you threw the ball up to serve, the homely wooden buildings…”

Local involvement

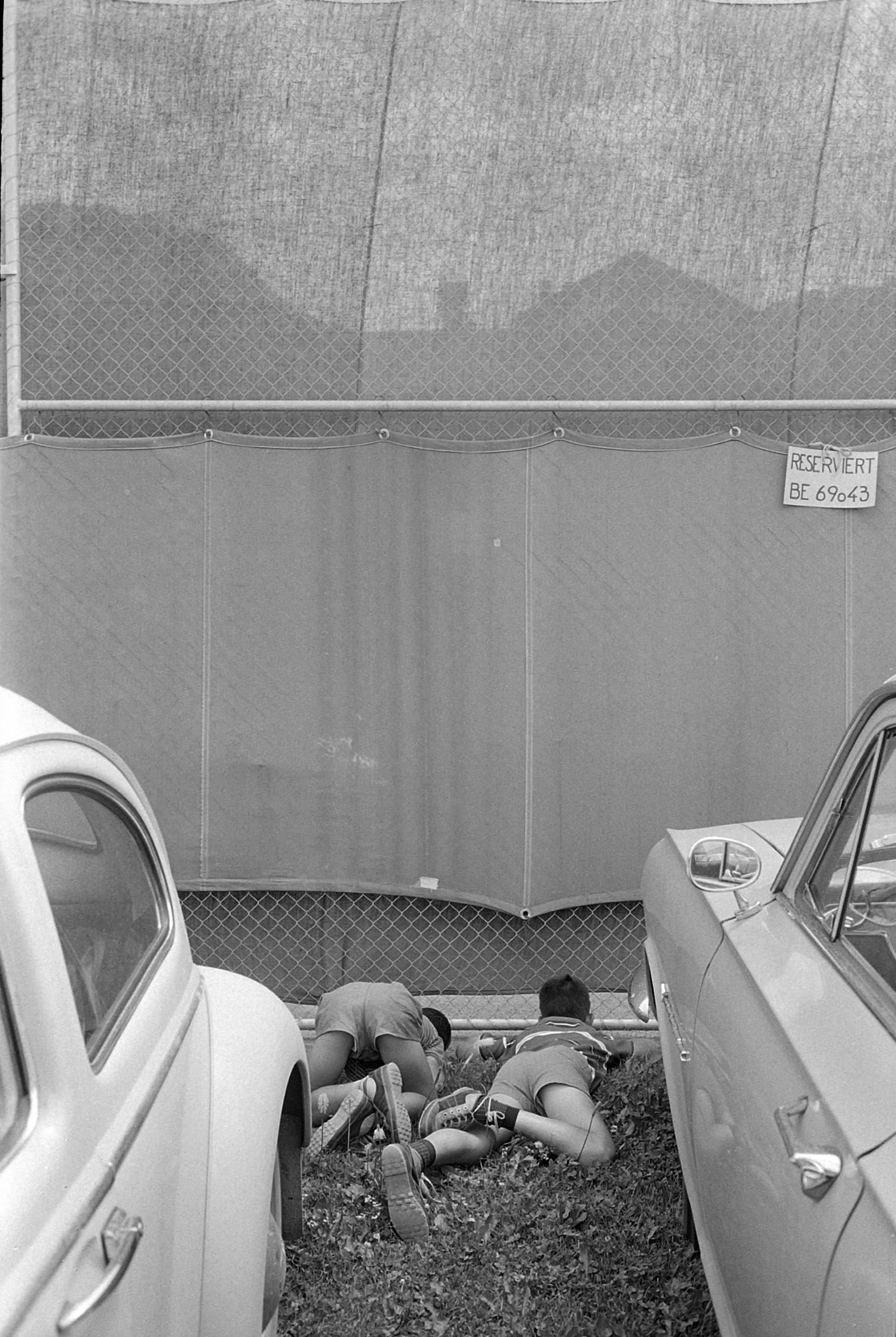

It is this intimacy, however, that is the biggest challenge for organisers. “The tournament really is in the middle of the village, surrounded by chalets, and a square metre is quite expensive!” Finkbeiner said.

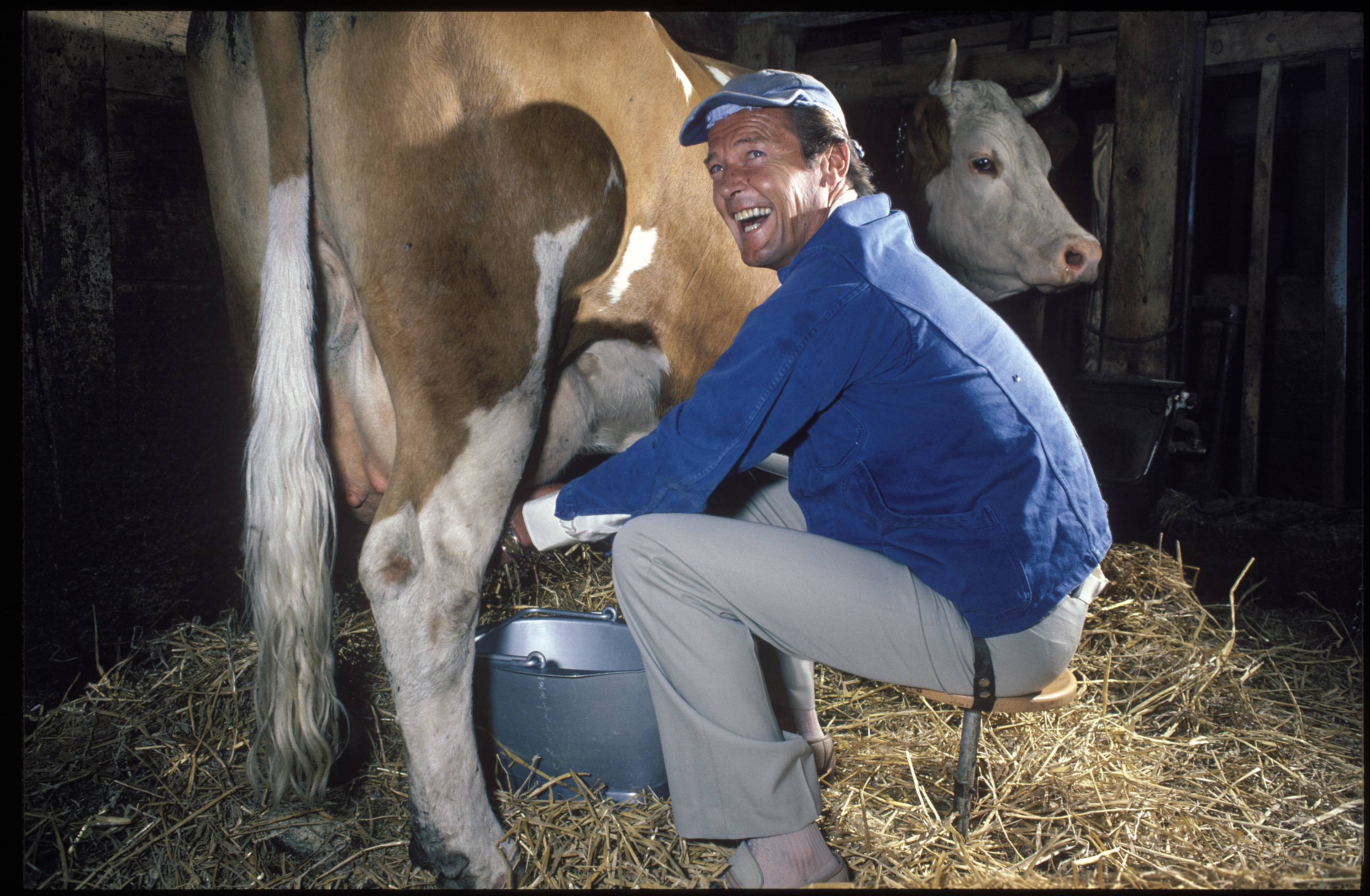

“We managed to build a 5,000-seat stadium [named after Emerson] but we also need a public area for food and drinks, public transport and parking and so on. You basically park your car in a field normally used for milking cows! We really are part of everyday life in Gstaad. Every citizen of Gstaad has worked at least once for the tournament.”

Martin Bachofner, director of Gstaad Tourism, agrees. “Without voluntary work, this tournament would not happen. The reputation that the tournament has now is the result of decades of experience.”

“Sport” magazine wrote in 1994: “Gstaad, the Wimbledon of the Alps. Definitely not. If anything, Wimbledon is the Gstaad of the lowlands. It is not purely down to the beautiful landscape: it’s the distinctive, unique, incomparable atmosphere that makes it what it is, and this can be attributed to the village residents.”

Not that it has always been plain sailing. The Swiss Open Gstaad has had a few financial problems over the years and nearly double-faulted a few times, notably 1965, 2001 and 2005.

“There was some financial trouble in 2004/5 but that was due to terrible management,” Finkbeiner said. “Our company and the city of Gstaad took over the tournament and saved it in 2006. So there was a question mark then, but thanks to the local population and local support we could run the tournament smoothly.”

Added value

The Swiss Open Gstaad is also the largest tennis tournament in the world in relation to the local population, which balloons from around 7,000 (including surrounding villages such as Saanen and Schönried) to 40,000 when the tennis circus is in town.

“We have about 5,000 added overnight stays because of the tennis tournament,” Bachofner said. The reason this figure is not higher is that around two-thirds of spectators are Swiss who are visiting for the day.

“The University of Bern carried out a study a few years ago and found that added value from the tennis tournament is worth about CHF10 million ($10.5 million) – consumption in restaurants, overnight stays, shopping and so on,” he said.

“Not many people watch tennis all day all week. Maybe they want to see other things – they might go up a mountain, so the cable car company benefits, or have some spa treatments.”

Federer effect

One visitor who took in the sites was Roger Federer, who made his professional debut at Gstaad in 1998 aged 17. Ranked 702 in the world, he lost his first match without winning a set.

“My appearances in Gstaad in 2003 and 2004, when I arrived as Wimbledon champion, were crazy. Everything seemed to interest [the media]. People even wanted to know whether I’d eaten croissants or muesli for breakfast. They were surreal weeks,” he wrote.

Federer won the tournament in 2004 but has only played once since then – losing in the first round in 2013. He’s not scheduled to play this year.

“It’s a scheduling clash – it’s the same for all the top-ten players,” Finkbeiner said. “We’re in between Wimbledon, which is played on grass, and the hard court season in America, and this is usually holiday time for the big players.”

He says they have considered moving dates, but it’s “just not possible”. “There are 60 World Tour tournaments throughout the year. When you are part of the ATP, you receive the right to play on a certain week on a certain surface. Two or three years ago we bid to move dates and play on grass, but for technical reasons we could not organise a grass tournament in the mountains.”

Despite this, Finkbeiner says the Swiss Open Gstaad is in good health. “We’ve had extraordinary luck over the past ten years to have had two world-class Swiss players, Federer and Wawrinka.”

When Federer broke his self-imposed Gstaad exile in 2013, Bachofner said it was “crazy, really amazing – we had 50% more reservations”.

And the highlight this year? “Wawrinka winning! But first of all a Swiss grand slam winner at Roland Garros playing at Gstaad is really rare. With Roger Federer we tend to forget that – but he’s from another galaxy!”

[UPDATE: late on July 23 Wawrinka announced he was pulling out, citing a shoulder injury]

History of Swiss Open Gstaad

1915: Gstaad Palace Hotel hosts a men’s singles tournament, organised by the Lawn Tennis Club Gstaad, on clay courts laid in 1913. Despite the club’s name, tennis is never played on grass in Gstaad. The winner is Victor de Coubasch from Russia.

1930: three courts are built in the middle of village.

1932: the Swiss championships are held on both sites and are one of the first tournaments to feature ball boys and umpires.

1939: the championships are held throughout the war but the standard drops as only players who are deemed unfit for military service or international players who are “not significantly affected” by the war are able to take part.

1949: the “Drobny affair” thrusts Gstaad into the media spotlight. Czech envoys try to bring home two Czech players, including Jaroslav Drobny, who is due to play a Spanish player, representing the Franco regime and therefore a political opponent of Czechoslovakia. The envoys are not allowed into the Palace Hotel, where the Czech players are staying and return to Bern empty-handed.

1969: the finals are broadcast on Swiss television. The tournament starts on same day that Neil Armstrong lands on the moon (July 20).

1973: boasts a high-calibre field as many top players who boycotted WimbledonExternal link come to Gstaad.

1980: Heinz Günthardt becomes the first Swiss to win the men’s final since the war. Federer would then win in 2004.

1984: the women’s competition is scrapped as a result of competition from Lugano and Zurich.

1988: a political attack! A mishit return hits former Swiss President Pierre Aubert in the stomach. He’s fine and presents the trophy to the winner.

2003: Wimbledon winner Federer is given a cow, Juliette.

2005: the tournament loses CHF1.2 million. Files a debt restructuring moratorium in early 2006.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.