How we went from sundials to smartwatches

The fascination with time has inspired countless interfaces, none more radical than the recent smartwatch. At the heart of a region renowned for fine traditional watchmaking, an exhibition reveals how the division of time by mankind more than 5,000 years ago continues to foster ingeniousness and creativity.

Telling Time at Lausanne’s Mudac design museum focuses on the capture of time by watchmakers, designers and artists from the 16th century to today, including the brazen newcomer, the Apple Watch.

For 30 years, Fabienne Xavière Sturm was in charge of the famous collections of the Museum of Watchmaking and Enamelware in Geneva, which she presented all over the world, but when she was invited by Mudac’s director, Chantal Pro’Hom, to co-curate the Lausanne exhibition, they rapidly decided to concentrate not on watchmaking or time itself, but on the way timepieces tell time.

“We look at the face of a watch the same way as we look at the face of a person, we read its traits to understand what it is telling us, each one with a different expression, some mysterious, some playful, others secretive or joyful.”

With more than 150 examples in diverse styles from different ages, including from the great watchmakers of history – Vacheron Constantin, Cartier, Piaget, Audemars Piguet, Jaeger-Lcoultre, and IWC – the exhibition is a tribute to man’s poetic hold on time.

More

Infinite ways of telling time

The origin

The division of time into hours probably dates back to 3,500 BC explains the show’s historical advisor Arnaud Tellier, former director of the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva. It has been attributed to a semi-nomadic tribe, the Chaldeans, who settled in southern Babylonia, currently Iraq, and whose astrological observations led to the numerical division of time.

The Chaldeans noted that it takes 360 days for the same pattern of stars to appear in the sky and began by dividing the year into six periods of 60 days. The so-called sexagesimal system is believed to have been chosen because 60 is the smallest common multiple of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, therefore divisible by all six numbers.

The later division of the hour into 60 minutes (from the Latin for small) and 360 seconds (for ‘second minute’, following the second division of the hour) repeated the same pattern and is also said to be at the origin of the 360 degrees of the circle.

The Chaldeans further divided the day into six time intervals, three for day and three for night. Consequently the length of the intervals was variable, depending on the time of year and location. Using a sundial, the Egyptians then divided the day into 12 intervals, probably to reflect the number of lunar cycles in a year and then subsequently into two periods of 12 intervals, the second one for night.

Invention of timepieces to keep time

It was only with the invention of mechanical timepieces in the 13th and 14th century that the length of hours could at last be anchored into a fixed time. According to Tellier, the first clocks were created to regulate the cycle of prayers in the monasteries after dark.

With the invention of the pendulum around 1660 and the spiral balance in 1675 by the Dutch mathematician, astronomer and physician, Christiaan Huygens – who was inspired by the works of Galileo – clocks and portable timepieces could at last tell the minutes and not just the hours.

A springboard to imagination

Wandering hours, day and night dials, ‘grandes complications’ with the phases of the moon, lavishly enamelled dials with portraits of royalty, circles, squares and triangles, the telling of time has been nurtured by infinite imagination.

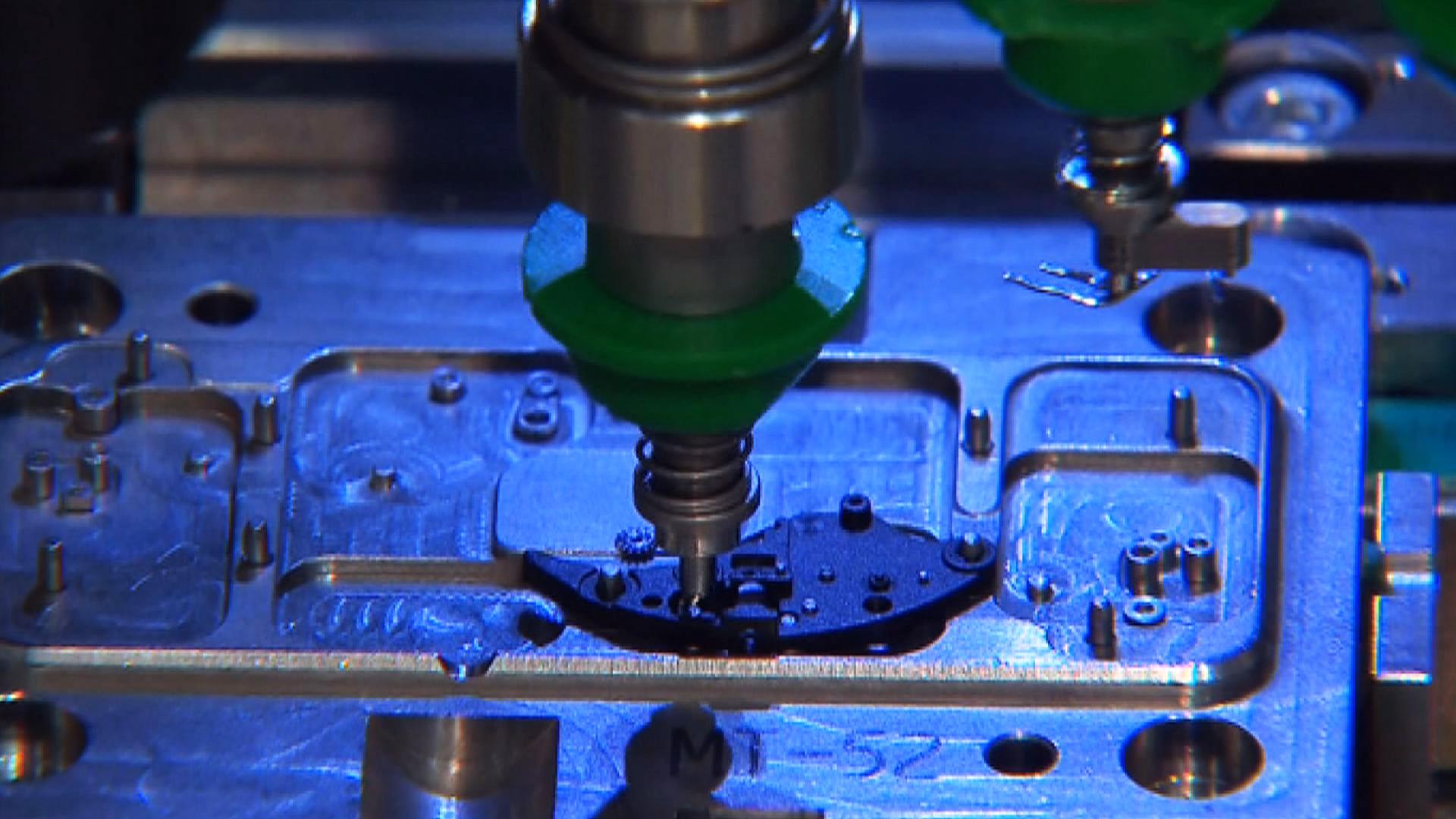

Sturm points out however that this has not always been the case. Timepieces were originally made by clock and watchmakers alone. Then merchants stepped in and entrusted the many stages of the production to different craft masters, including engravers, relief carvers, jewellers and enamellers.

Geneva played an important role in establishing Switzerland as a pivotal player in the field. The harsh climate of the neighbouring Jura allowed the manufacturing to take place during the winters when the farmers had nothing to do.

It is no surprise, according to the co-curator, that designers and artists later came to use time as a springboard to their own imagination and their proposals make up a large part of the show.

Using flip dials, videos, lashes, knitting machines, paper cut-outs, or beads, world-famous contemporary artists such as Darren Almond, John Armleder and Gianni Motti join young designers to invent quirky, ingenious, bizarre and amusing new ways to capture time.

What next

The decision to end the selection with the connected watch conveniently opens the door to the future. ECAL, the internationally renowned University of art and design Lausanne, has ensured the scenography of the show, but very few of its students, director Alexis Georgacopoulos points out, even wear a watch. He thinks however that vintage models, particularly those bold designs from the 60s and 70s, are making a comeback.

As for the Apple Watch, Georgacopoulos suggests that its success will also depend on whether it is renewed as frequently as the phone. He adds somewhat provocatively that it should jolt the top-end watch industry into action.

One brand has already responded. Jean-Claude Biver, CEO of Tag Heuer, has announced the launch of a Swiss smartwatch by this autumn. He hopes that Apple will sell “millions and millions” so that young people will start wearing watches again, but will turn to different brands when they tire of owning the same as everyone else.

The Zurich-based Smartwatch Group predicts that 27 million smartwatches will be sold this year, with sales climbing to 650 million by 2020.

By combining heritage collections with playful contemporary designs, Telling time has provoked a dialogue between history and the present that teases our perception of time.

“This is not just about objects. Philosophy is never very far away,” advances Xavière Sturm.

Telling Time – the exhibition

Telling Time displays six centuries of timekeeping with 150 objects from all over Europe. The historical pieces are from both private collections and major public repositories. The scenography of the exhibition is a result of a partnership with the ECAL/Ecole cantonale d’art de Lausanne, and is the work of students on the Exhibition Design course led by industrial designer Adrien Rovero.

The Mudac

Lausanne’s design museum is an established presence on the international design circuit. Its thematic exhibitions bring the pool of local talent in contact with designers the world over. In contrast to design in the German-speaking part of the country, which for decades has been recognised for its robust functionality and minimalism, the French-speaking regions have spawned a generation of designers who are fresh, playful and inventive. This spirit is captured by Mudac’s director Chantal Prod’hom who used to head Asher Edelman’s Lausanne art foundation and Benetton’s La Fabrica.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.