Early climbers banish dragons

Men have been crossing the Alps for millennia. As far back as Roman times, roads threaded up alpine passes, used by pilgrims, merchants and entire armies. But not until the 19th century did mountain peaks themselves become a goal.

A 16th century Swiss scientist, Konrad Gesner, climbed mountains and by doing so, challenged the widely held belief of the time that dragons inhabited the Alps. “As long as it may please God to grant me life, I will ascend several mountains, or at least one, every year, at the season when the flowers are in their glory, partly for the sake of examining them, and partly for the sake of good bodily exercise and of mental delight,” he wrote.

But superstitions lingered. As late as 1723, a respected Swiss scholar, Johann Jakob Scheuchzer, published a lengthy treatise on the Alps that included illustrations and accounts of the dragons living on the mountaintops.

Oddly enough, it was the appearance over the following decades of poems and novels romanticising the Alps that helped dispel the feared image most people had of them. The Geneva naturalist, Horace Bénédict de Saussure, put the final nail in the coffin of the alpine dragon.

De Saussure was obsessed with Mont Blanc – at 4,807 metres above sea level, the highest mountain in Western Europe. Like Gesner and Scheuchzer before him, he wanted to explore the mountain for the sake of science.

After his own failed ascents, he put a bounty on the head of Mont Blanc. Two Frenchmen from Chamonix were able to claim the reward in 1786.

De Saussure’s accounts of his successful climb a year later attracted a wave of scholars, artists and writers to the Alps. Thanks to a revolution in mapmaking set off by Napoleon’s engineers, visitors could also plan their routes better. So, by the beginning of the 19th century, the Alps were portrayed in scores of scientific documents, prose, pictures and maps.

Poetry piques curiosity

Not least among the artists were British writers like Wordsworth, Byron and Shelley, whose words drew even more attention to the picturesque Alps.

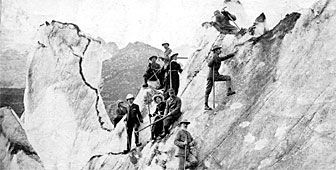

Most of the British tourists stuck to the valleys and lakes. A few ventured over alpine passes, but only the most courageous or foolhardy attempted to climb the mountains. Those who did, British and other Europeans, followed de Saussure’s lead and made scientific observations.

But by the 1850s the tide had turned. Upper class gentlemen and scholars who took on the peaks for sheer adventure began to outnumber the scientists. The British showman, Albert Smith, turned his ascent of Mont Blanc in 1851 into a popular London stage play, and only a few years later, Alfred Wills’ account of his own exploits in “Wanderings among the High Alps,” proved that climbing could be an end in itself.

The golden age of mountaineering had begun. “We felt as in the immediate presence of Him who had reared this tremendous pinnacle,” Wills wrote of his ascent of the Wetterhorn above Grindelwald. “And beneath the ‘majestical roof’ of whose deep blue Heaven we stood, poised, as it seemed, half-way between earth and sky.”

Wills had ample support from some of the great thinkers of the day, including Leslie Stephen, who threw down the gauntlet to scientists in the climbing community in a famous address to the fledgling Alpine Club.

His jests concerning scientific observation divided the association, and led to resignations by prominent members.

But most travellers to the Alps followed Smith, Wills and Stephen. They came to conquer. As British naval fleets colonised the remotest corners of the globe, British adventurers claimed alpine peak after alpine peak.

In Switzerland, they found a people willing to oblige. Villagers learned the craft of guiding and entrepreneurs built grand hotels on mountain slopes, offering service fine enough for the “English lords”.

The 19th century climbers sought adventure as much as they sought the natural beauty of the Alps as a refuge from the blight of the industrialised British landscape.

Racing through “cathedrals”

The unprecedented assault on the Alps reached its highest – and lowest – point in 1865 with the first ascent of the majestic and challenging Matterhorn.

The success of the Matterhorn expedition, led by Edward Whymper, was marred by tragedy when four members of the party fell to their death during the descent.

It was to spell the end of mountaineering’s golden age, but the British kept coming, and according to 19th century writer John Ruskin, they were unknowing accomplices in the disfigurement of the landscape they cherished so much.

“You have made racecourses of the cathedrals of the earth. Your one conception of pleasure is to drive in railroad carriages round their aisles, and eat off their altars…the Alps themselves, you look upon as soaped poles in a bear-garden, which you set yourselves to climb, and slide down again, with ‘shrieks of delight’.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.