Embryos harvested to create stem cell crop

Swiss scientists have succeeded in producing a crop of human embryonic stem cells (HES) as part of a four-year research period permitted by the government.

Changes in Swiss legislation in 2004 gave the Geneva University team a window of opportunity until 2008 to study embryos that had been donated for research before 2001.

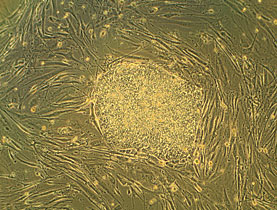

The team has developed its first successful line of stock of HES cells from which further research can now be carried out.

In contrast to most stem cell development, the team was able to produce cells in conditions free from animal components, the use of which raises ethical concerns and a risk of transmitting germs.

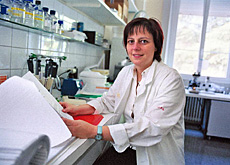

“For us it’s a success. This line has been derived without exposing the cells to animal components, like foetal bovine serum, which is the case in most of the lines available in the different laboratories now,” Marisa Jaconi, project leader at the university’s faculty of medicine, told swissinfo.

“But we would have been happy even without this successful line. It was a great opportunity to start this project, to learn and to gain all the know-how of doing it.”

Hard work

Switzerland passed an amendment in 2004 to the 2001 medically assisted procreation act that banned the freezing of embryos beyond the zygote, or impregnated egg, stage.

The law dictated that all leftover embryos that were frozen before 2001 had to be destroyed by 2005. But in 2004, the government ruled that surplus embryos could be kept until 2008 if donated for research.

The team was given the go-ahead for the project in 2005 after approval by the institutional ethics research committee of the Geneva University Hospitals and the Federal Health Office.

Two groups from the university’s medical faculty and the gynaecology and obstetrics department worked on 203 embryos that had been donated from seven in vitro fertilisation centres around the country.

Most of the embryos had been frozen between 1979 and 2000. But the success rate of reproducing cells was minimal, as many of the embryos were unhealthy or did not survive thawing. The likelihood of success was further diminished by using frozen embryos which have a reduced chance of development and thus of providing a line of cells.

“We quite expected this given the old age of those embryos. The problem was that their quality was so low that it was hard work. We did what we could with what we had,” explained Jaconi.

Cancer link

The team managed to derive a line of cells from an unhealthy embryo, which was then cultivated on human skin fibroplasts and transplanted into mice that did not have immune systems.

Researchers expected the cells to form benign tumours – useful research tools containing almost all cell types – but instead they developed into more cancerous growths.

“It is the first tumorigenic line of HES cells derived from a single cell of a human embryo,” said Jaconi.

“We can now study why this line formed very aggressive tumours. It could constitute a useful research tool for studying cancer.”

Jaconi said previous lines of embryonic-like stem cells were developed in the 1960s from malignant gynaecological tumours.

She said she hoped the results would enable her team to better process future embryos that are donated for research.

The findings were reported to stem cell registry of the Federal Health Office and published in the Swiss Medical Weekly journal.

The stock will be used by the International Stem Cell Forum, which brings together 14 laboratories worldwide and encourages collaboration in stem cell research.

It has been banked in the team’s laboratories and may also be introduced to the European Registry of Embryonic Stem Cells.

swissinfo, Jessica Dacey

Marisa Jaconi says a maximum of three impregnanted eggs can be developed at a time for IVF. While centres often develop three eggs in case there are problems with one of them, not all would be implanted because of the risks to the baby’s health and of multiple pregnancy.

Scientists are only made aware of those embryos made available to research at the very last minute.

For research to go ahead permission has to be granted by the Federal Health Office and the Federal Ethics Commission.

Swiss researchers cannot import surplus embryos from abroad. More embryos could be counted as being surplus if pre-implantation genetic diagnosis was introduced in Switzerland.

This would allow couples with serious hereditary genetic diseases to have embryos that are artificially conceived to be tested for those diseases. Embryos that are not implanted could be then donated for research. However, there are currently no plans for the law.

Stem cells are unspecialised cells, which can develop into any part of the human body.

Because of this potential, researchers believe it will be possible one day to use them to fight degenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s.

Stem cells are present mainly in the early stages of life, when the cells of a fertilised egg begin to multiply before developing into a human baby.

They are also found in the umbilical cord, amniotic fluid and in the adult organism, but their potential is more limited than that of embryonic stem cells.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.