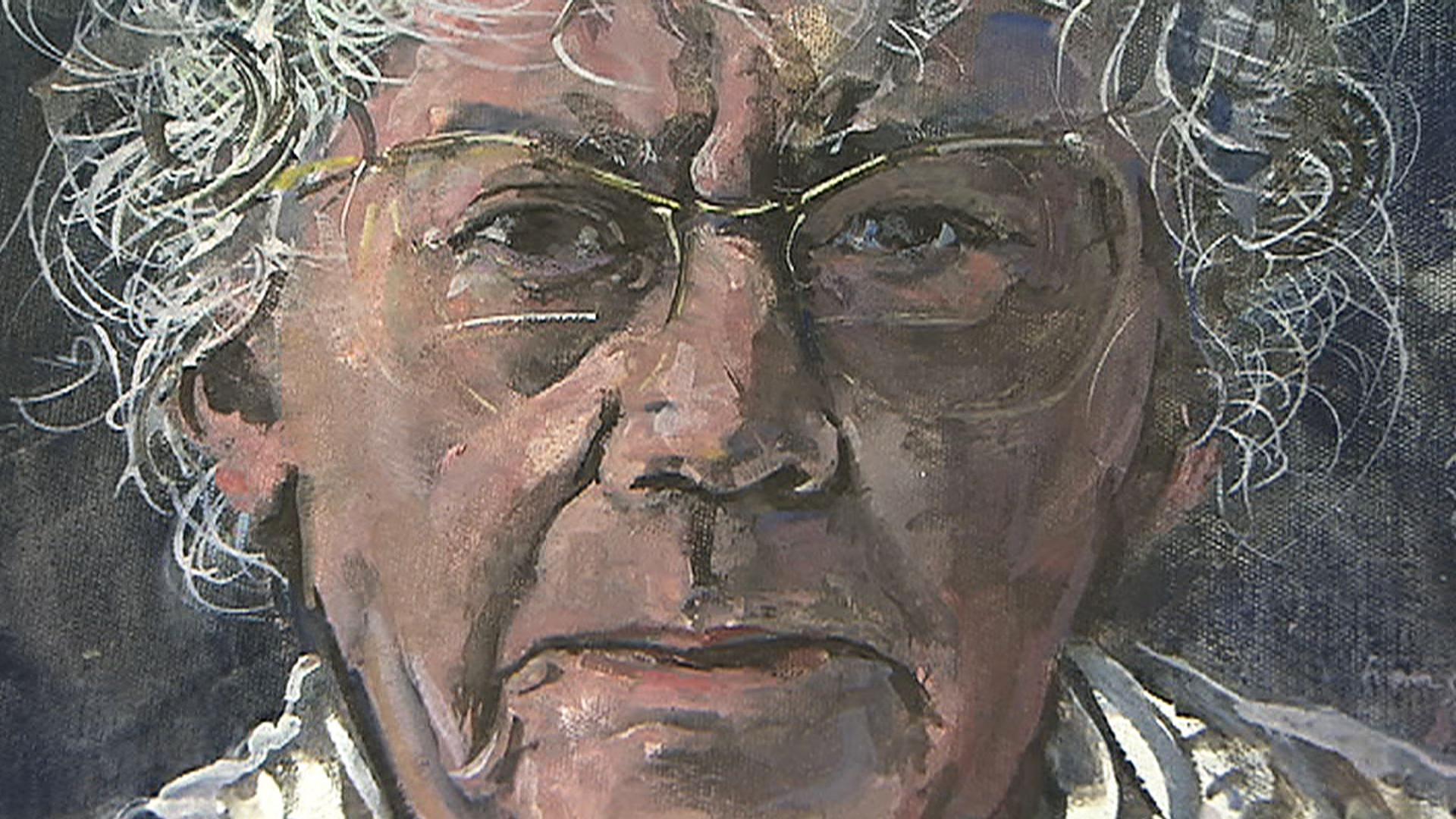

Remembering Max Bill, the one-man Bauhaus

On the centenary of Bauhaus, the influential German design school, a major exhibition in Zurich is devoted to Swiss all-rounder Max Bill. His widow, who curated the display, gives swissinfo.ch a personal insight into the man and his legacy.

“The biggest challenge was that we had more material than we could show!” says art historian Angela ThomasExternal link, who on Bill’s death in 1994 inherited half of his works and half of what he had collected.

“At first we wanted to show only smaller format works, but then we thought it would be a shame because the room is so high. So we fetched the three larger pictures and took out a couple of smaller pieces.”

The final selection for “max bill: bauhaus constellationsExternal link”, running at the Hauser & Wirth gallery until September 14, includes paintings and sculptures that Bill created after his time at the Bauhaus, from the 1930s to the 1980s. They appear alongside a range of smaller works by connected Bauhaus artists, Bill’s teachers and some of his fellow students, as well as archive materials he gathered during his lifetime.

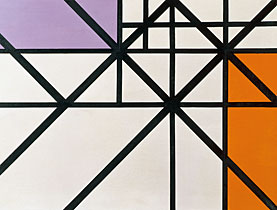

Important paintings on display, such as Bill’s “Horizontal-vertikal-diagonal-Rhythmus (Horizontal-vertical-diagonal-rhythm)” (1942) and “Reflexe aus dunkel und hell (Reflections from dark and light)” (1975), reflect many principles of colour and form taught by Josef Albers in the Bauhaus’s preliminary course.

“Max Bill’s work is very broad – you could say from aggressive to lyric or poetic,” says Thomas, who is also president of the Max Bill Georges Vantongerloo FoundationExternal link. “Some of his pictures have soft colours that you might think had been painted by a woman.”

These paintings and several sculptures recall the essential shapes of Bauhaus design – the triangle, circle, and square – which feature heavily throughout Bill’s oeuvre. And while they echo the aesthetics of his contemporary Piet Mondrian, Bill was also strongly influenced by Bern-born Paul Klee, with whom Bill could speak Swiss-German.

+ Switzerland and the Bauhaus – 100 years of functional elegance

Fascination with modern architecture

Max Bill was born in Winterthur, northeastern Switzerland, in 1908. Originally studying as a silversmith’s apprentice in Zurich, he became fascinated with modern architecture when he encountered Le Corbusier’s L’Esprit NouveauExternal link and Konstantin Melnikov’s pavilion for the USSRExternal link at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925.

After the destruction of the First World War, a sense of freedom and radical experimentation swept across the art scene in Germany.

In 1919 architect Walter Gropius founded the theoretically apolitical Bauhaus (literally “building house”) school in the city of Weimar with the aim of creating consumer goods which were functional, cheap and able to be mass-produced yet which left room for artistic individuality.

The Bauhaus moved to Dessau in 1925 and then Berlin in 1932 before closing in 1933 under pressure from the Nazis. But its teachers and students spread all over the world – many moved to the United States. This ensured its ideas would have a lasting influence on many fields including painting, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design and typography.

Shortly after this, he discovered Weimar-era Bauhaus materials in a bookshop in Zurich, edited by the school’s German founder, Walter Gropius, and Hungarian artist and Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy. After learning that a new Bauhaus was to open in Dessau in 1926, Bill applied and was accepted in April 1927 aged 18.

While Bill was fortunate in many respects – Thomas says he was “really lucky to have so many talented and innovative masters” – his time at the Bauhaus was cut short when a trapeze artist landed on him, knocking out several teeth. The resulting dental bills, largely paid for by borrowing money from his father, meant he couldn’t afford to stay on in the Bauhaus.

But he seems to have taken that twist of fate in his stride. “He had a lot of humour,” Thomas remembers. “We have a small watercolour in the vitrine called “Der Kleine Jammer König” (the little king of complaining) which is self-ironic as he never complained. When he lost an eye because of a tumour he never complained, not once.”

She explains how Bill left the Bauhaus after two years without a diploma “but with a lot of energy and ideas”. To earn a living – and to pay off his debts to his father – he initially painted film posters and worked as a typographic designer, including for anti-Nazi publications sent to Germany.

‘Max Bill, architect’

Bill seems to have been a one-man Bauhaus – architect, sculptor, artist, industrial designer, graphic designer, typeface designer and, later, teacher at the Ulm School of DesignExternal link. Although Thomas says one discipline was particularly close to his heart.

“Above all he would have loved to have been an architect. Whenever we stayed the night in a hotel, he would sign in not as an artist but as “Max Bill, architect”. But he didn’t get so many commissions.”

That said, he did design Haus Bill, which was built in Zumikon, near Zurich, in 1967 and which functioned as Bill’s home and studio. Today, it is home to not only Angela Thomas but also the Max Bill Georges Vantongerloo Foundation.

Like many left-leaning artists at the time, Bill had a complicated relationship with Switzerland. Indeed during the Second World War the Swiss authorities ruled him a “left-wing extremist” to be interned in case of war.

“In 1936, when Bill designed the Swiss pavilion in Fascist Italy and chose what was displayed, he won the Grand Prix – but in the name of the pavilion, not his personal name,” Thomas says. “In Zurich in the 1930s there was a pretty reactionary atmosphere and in the press the people in Zurich accused what he had done there of being ‘unSwiss’. And despite this great result they didn’t let him officially take part in the National Exhibition in 1939External link.”

She also explains how, when in 1951 he won first prize for his sculpture at the first São Paulo Art BiennialExternal link, the Swiss papers referred to “the Swiss Max Bill”. “And that irritated him. He said ‘I won as an artist, not as a Swiss’. He always thought internationally.”

This archive video from 1968 shows Bill at an exhibition devoted to him at Zurich Art Museum:

Picking up the Bill

As the exhibition explains, through his pursuit of a new visual language that could be understood by the senses alone, Bill defined the conventions of Swiss design for decades to come.

So a quarter of a century after his death, are his works collectable?

“Yes, but I’ve made only very few available for sale,” Thomas says. “The demand is certainly there. People here wanted to buy the large painting [Untitled, 1970] but I didn’t want to lose it.”

“When I and my second husband die, we want to give [Haus Bill] back to society and therefore I want to hang onto a certain number of Max Bill’s original works which can then continue to be displayed,” she explains.

Those Bill works that do make it to auctionExternal link often comfortably exceed estimates. For example “Zerstrahlung von Orange” (1972-74), a 62.5cmx62.5cm oil on canvas, went for €80,000 (CHF88,000) in 2016. Last year a granite sculpture, “Strebende Kräfte einer Kugel” (Striving forces of a sphere) (1985-86), was sold for €300,000, beating the estimate of €250,000.

‘Love story’

When it comes to Bill’s life outside the studio and his personality, Thomas says her first husband was a workaholic.

“He told me he would start a creative work to recover from another one. He was also a womaniser – so he had very good organisational skills!”

He was also modest and interested in other people. “For example when he was vice-president of the Academy of ArtsExternal link in Berlin, an Irish journalist came and asked if Bill could tell him something about James Joyce in Zurich! And he did so without further ado – he wasn’t all ‘why aren’t you asking about me?’.”

As for their own relationship, she says it was a real love story.

“It was very interesting for me because he moved in various circles. I was 40 years younger than him. He was 65 when I met him and I was 25 and we fell in love. It wasn’t the general case that I preferred older men, but he was simply his age and I was my age; I always said I would have also taken him had he been younger!”

1908: Max Bill born in Winterthur on December 22

1927-28: studies at the Bauhaus in Dessau under Albers, Kandinsky, Klee, Moholy-Nagy and Schlemmer

1929: works as a painter, sculptor, graphic designer, publicist and architect in Zurich

1931: marries Binia Spoerri

1939-45: military service

1942: birth of son, Jakob

1944: first exhibition ‘Konkrete Kunst’ (concrete art) at Kunsthalle Basel; beginning of work in design

1951-56: architect and rector of the Ulm School of Design

1961: elected to Zurich’s city parliament

1967: elected to the House of Representatives (until 1971)

1974: meets student Angela Thomas in Zurich

1987: designs a five-franc coin to mark 100th birthday of Le Corbusier

1988: death of Binia Bill-Spoerri

1991: marries Angela Thomas

1993: presented with the ‘Nobel prize for art’: the fifth praemium imperiale in Tokyo

1994: Dies at Berlin airport on December 9.

For a much more detailed biography click hereExternal link

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.