Experts visit Geneva’s papyrus treasures

“Has anyone seen any Menander?” A lone voice struggles amid the clamour of excited scholars hunting ancient treasures in the dim-lit underground museum.

swissinfo.ch caught up with papyrus experts who had taken time off from an international congress in Geneva to marvel at the collection of precious manuscripts at the Bodmer Foundation in nearby Cologny.

“Ah, here we are… this is the high point,” exclaims Peter Preston, a retired professor of Greek at Oxford University, as he elbows his way past several colleagues to a glass display case.

Inside are thin tobacco-coloured papyrus sheets from the Dyskolos (The Bad-Tempered Man) – one of three “lost” comedies by Menander, a popular Greek playwright of the fourth century BC.

“It looks as if someone might have stuck a spade through the corner and damaged it slightly, but it’s almost perfect,” Preston says.

Menander was an ancient dramatist, described as “the father of sitcom”, who was rediscovered last century after papyri fragments containing his writings were unearthed in Egypt, then put back together by papyrologists and published in the late 1950s-60s.

“He was once one of the greatest playwrights of his time and he suddenly disappeared,” Preston explains. “Our work is really a way of bringing back authors from the dead.”

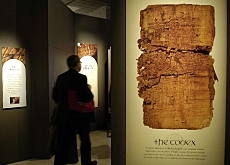

The Menander comedies are just a small part of the Bodmer Foundation’s collection of 27 papyri – including texts from the Old and New Testaments, early Christian literature and Homer’s Iliad – which were discovered in Egypt in 1952.

“This is the third-most important collection of papyri after the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi finds,” says museum director Charles Méla.

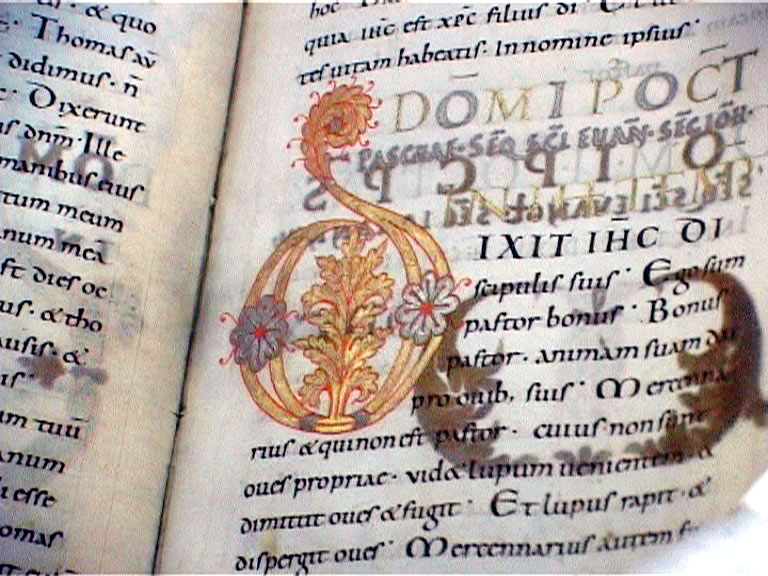

“We have exceptionally put together a selection of very beautiful examples from our collection for you today,” he says, pointing at two other display cases, one of which contains an extract of the Gospel of St John in Greek from 200AD, one of the most ancient New Testament manuscripts known to exist.

“It’s incredible what they have here – to die for,” whispers one specialist to his colleague.

Broad scope

The visit to the Bodmer Foundation, located in Geneva’s “Beverly Hills”, is a side event for the 300 experts who have been attending the 26th International Papyrology Congress.

Papyrology is the study of ancient literature and documents preserved in manuscripts written on papyri mostly in Greek, the official language of communication in Egypt for 1,000 years. But they also exist in Coptic, Aramaic, Arabic and Egyptian.

“The congress is broad, covering archaeology, history, literature and religion,” explains Paul Schubert, professor of Greek at Geneva University and organiser of the event that takes place every three years.

But this year has seen a special focus on archaeology.

“We now have texts that allow us to reconstruct what villages or cities looked like, so we can superimpose them against actual excavations,” he said.

Modern techniques

During the week, academics from around the world presented new research and exchanged techniques and ideas aimed at helping extend existing knowledge of the ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman civilisations.

“We heard about new fragments of papyri from tragedies written in the Hellenic period about biblical topics, which is very unusual as they are usually about classical tragedies like Sophocles or Euripides,” Schubert said.

Modern technologies such as the internet are a great help for papyrologists, especially for jobs like sorting through the masses of existing material and for networking. And in future it may even be possible to scan through a papyrus roll and unroll it virtually, he added.

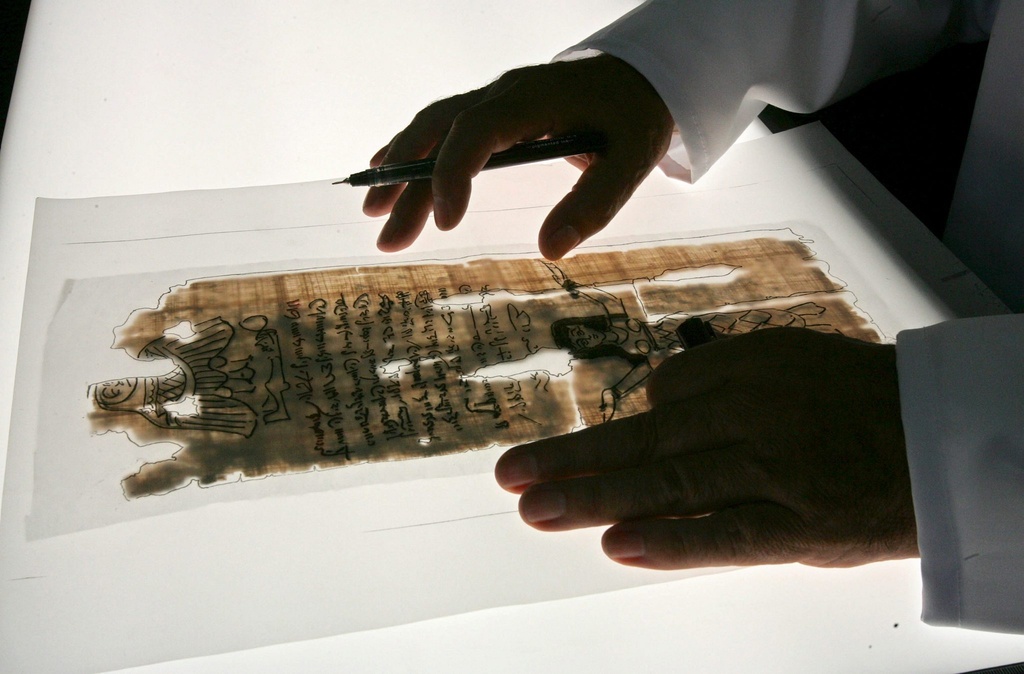

Although specialists are increasingly using digital images to piece together fragments on their screens, they still rely on basic skills, the original papyrus and a simple microscope.

Sharp eyes

“You have to know your Greek, have a good eye to be able to date it according to the writing and see how the pieces fit together, as well as figure out the texts in the gaps,” Schubert said.

Preston agreed. “You need sharp eyes and to allow for the fact that the papyrus is torn up, battered or covered with old cabbage leaves. You need to think in Greek and imagine that it came from real people – maybe a copy of Homer belonging to a schoolboy or a butcher’s list of chops that he’s going to eat when he gets home.”

Thanks to the huge bulk of documentary evidence – letters, contracts, bills and so on – Egypt is the place in the Mediterranean where we have the most details about daily life, Schubert said.

But papyrology has also given us insights into areas of Greek literature, such as lyrical poetry by authors like Sappho or Ibycus, where our knowledge was only limited, he said.

New finds

Meanwhile, new papyri continue to be unearthed in their thousands at sites on the edge of the desert in the middle of Egypt, but it is a race against time to excavate everything in locations where locals have started to irrigate.

Today’s digs uncover only small amounts of papyri compared with those found in Egypt at the end of the 19th century at places like Oxyrhynchus, situated 160km southwest of Cairo. There, experts unearthed the town’s rubbish tip with thousands of papyri that had been preserved under the sands.

New material also comes from museum cellars, said Preston. “At Oxford they have 50,000 papyri that still need to be edited.”

But there are other more unusual sources, like Egyptian mummy sarcophagi, some which are made of cardboard composed of papyri.

“If you soak them in new biological detergent, it dissolves the glue and the papyri come to the surface; you then just have to piece them together,” he explained.

Simon Bradley in Geneva, swissinfo.ch

The Bodmer Foundation, which was set up by Swiss academic and collector Martin Bodmer in 1971, holds a collection of more than 160,000 manuscripts and books, dating from antiquity to modern times.

The collection includes first editions of major works, including the Papyrus 66, which is one of the oldest almost completely preserved manuscripts of the Gospel of St John , the original of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, the only copy of the Gutenberg Bible in Switzerland, a string quintet by Mozart, Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, the manuscript scroll of The 120 Days of Sodom by the Marquis De Sade and original editions of Don Quixote and Faust, among others.

It also contains other valuable papyri, known collectively as the Bodmer Papyri. They include segments from the Old and New Testaments, early Christian literature, Homer and Menander.

The Bodmer museum, designed by Ticino architect Mario Botta, is located at Cologny, near Geneva, and is open to the public. Its permanent exhibition is supplemented by four temporary exhibitions each year.

The foundation is subsidised by canton Geneva (SFr500,000 a year), the commune of Cologny and private donations.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.