Going to work on a high

Joan and Martin Fischer earn their crust 3,500 metres above the earth's crust, a European record.

Shovelling snow, monitoring experiments, giving a bed to up to 20 scientists – the married couple who run the research station on the Jungfraujoch mountain ridge have their hands full all year round.

The day begins early: at 6am Martin, 44, is already clearing the snow from the observatory terrace on the peak called the Sphinx, which tops out at 3,571 metres. In any weather.

Because precipitation at this altitude almost always falls as snow and strong winds are the rule rather than the exception, snowdrifts are a daily reality on the terrace.

“In winter it’s still pitch black at six. When there’s a strong wind, every time you throw away some snow half of it blows back into your face,” he told swissinfo.ch. “That’s not such a fun part of the job – but it wakes you up…”

But before he can start doing that, he has to measure how much snow has fallen on a box housing scientific instruments. The researchers need this information so that they can make allowances for the impact the snow will have had on their data.

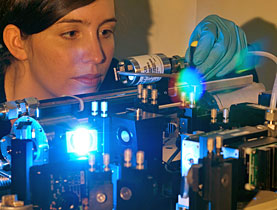

The instruments are devices for measuring cosmic radiation – one experiment of many up here. The advantage of the high-altitude research station is that the air is out of reach of cities, industry and traffic.

Never lonely

Meanwhile Joan Fischer, 40, is busy making life as comfortable as possible for the scientists in the station, which is next to Europe’s highest railway station.

The ten rooms for which she is responsible can accommodate up to 20 people – so the couple are never lonely, with 1,000-1,500 overnight stays a year.

“We run a sort of hotel. The scientists check in and out,” she said in a cosy pine-decorated room in the five-storey station, which, like the station, is built mainly inside the mountain.

“I look after the rooms, order the food, do the admin and give two or three tours a month,” she said.

Joan was born in the Netherlands and grew up seven metres below sea level – “we Dutch are pretty flexible”.

“At first it took a bit of getting used to,” she admitted, but added that even before they arrived eight years ago she loved the mountains.

“The surroundings are fantastic. It’s a special place. I like change and the contact with the scientists is very pleasant.”

Job requirements

Her husband takes down weather observations five times a day at fixed times. Standing at a window on the Sphinx he tries to assess the clouds: “visibility is roughly 30 kilometres, the sky is completely covered with altocumulus clouds at various altitudes.”

On a good day one can see for 160km – over the entire central plateau.

Martin Fischer sends everything that can’t be measured automatically to Zurich over the internet. The data are used by the national weather service MeteoSwiss for forecasts.

For this reason a certain interest in research and the weather – and technical flair – are essential for the job.

Previously Martin had worked, among other things, as a builder, blaster and lorry driver. He and his wife had maintained the station on the Schilthorn for three years before taking on the Jungfraujoch.

“I like the variety. There’s always something new to learn,” he said. “And we have a certain amount of freedom. Apart from the weather measurements we can spread the work as we want.”

Differences

The Fischers work at the station in three-week shifts and are then replaced for 11 days by another couple, the Seilers.

If they don’t travel abroad, they spend this time in Brienz, canton Bern.

“Back down in the valley after three weeks, there’s nothing nicer than going shopping in the supermarket and buying whatever I want,” Joan said. “Up here I miss the colours of flowers and grass.”

Martin finds people perceive things much more intensively at a lower altitude, for example one’s nose is much more sensitive – “which has advantages and disadvantages!”

Swiss engineer Adolf Guyer-Zeller put forward the definitive idea for the Jungfrau Railway in 1893 but the plans go back to about 1870.

The idea was that the railway would not start in the valley but from the Kleine Scheidegg summit station of the Wengernalp Railway, which was only two months old.

In an age of steam engines, Guyer-Zeller also decided that his railway had to be powered by electricity.

The railway to the 3,454 metre-high Jungfraujoch was completed in 1912, nine years later than originally planned. The costs were SFr14.9 million.

The cogwheel railway leaves the Kleine Scheidegg and goes into a tunnel through the Eiger and Mönch up to the Jungfraujoch station 3,454 metres above sea level.

The train travels about nine kilometres and climbs about 1,400 metres.

The line to the “Top of Europe” has been in increasing demand since its opening, except during the First and Second World Wars.

Last year a record 703,000 tourists travelled up the line, 12% more than in 2006.

(Adapted from German by Thomas Stephens)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.