‘The ‘saviour child’ is a really popular motif’

At a time of great social and political uncertainty in Europe, two nostalgic Swiss children’s classics have opened in cinemas within a couple of months of each other. A coincidence? A professor of youth literature and media explains the eternal popularity of stories like Heidi.

Ingrid Tomkowiak, professor at the Institute for Social Anthropology and Empirical Cultural Studies at the University of Zurich, tells swissinfo.ch about the latest big-screen versions of HeidiExternal link, which opens in cinemas in German-speaking Switzerland on December 10, and the very similar Schellen-UrsliExternal link (A Bell for Ursli), which since its release in mid-October has become one of the top ten biggest grossing Swiss films ever.

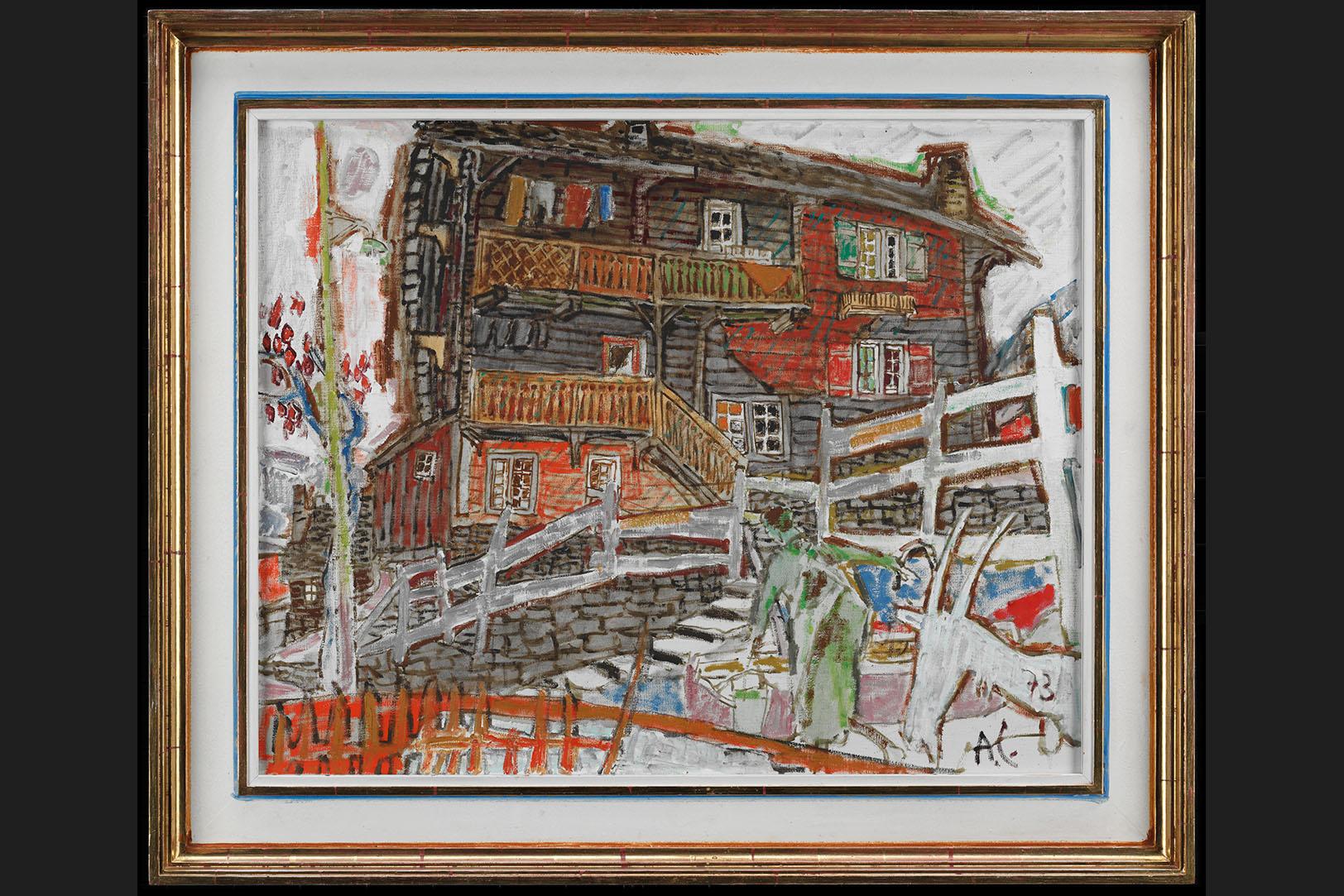

Many critics have noted similarities – and differences – between these children’s classics, set in beautiful alpine scenery and featuring a cute child who overcomes various challenges to create a happy ending, and the nostalgic and escapist ‘Heimatfilms’ of the 1950s and 1960s (see box). These were also filmed outdoors in dialect and emphasised the restorative powers of nature – a central theme of Heidi.

Heimatfilms, literally homeland films, were popular in German-speaking countries from after the Second World War to the early 1970s.

They were always shot outdoors, usually in the Alps or the Black Forest, and were noted for being sentimental and morally simplistic, with the focus on love, family, friendship and rural life – which was untouched by the problems of reality, i.e. war and destruction. Invariably a goodie and a baddie would fight over a girl, with the goodie winning. Many Bollywood films follow this template.

Switzerland, which wasn’t badly affected by the war, produced its fair share of Heimatfilms in the 1950s and 1960s, but one recent sub-genre that has found an audience is so-called New Heimatfilm. These focus on the differences between urban and rural (often alpine) way of life in Switzerland and the challenges these involve. They often have a fairytale quality.

Examples include Nur ein Sommer (2008), Sennentuntschi (2010), Der Verdingbub (2011), Clara und das Geheimnis des Bären (2012), L’enfant d‘en haut (2012), Die Schwarzen Brüder (2013).

swissinfo.ch: Why is there currently a revival of quasi-Heimatfilms in Switzerland?

Ingrid Tomkowiak: Whenever Heimat [literally “home”] reappears on the screen, it has something to do with a crisis – not necessarily an economic crisis, it can be a political crisis, a health crisis, but a crisis. People are searching for a place where they feel safe. In a crisis people have a longing for a healing place in the world and these are often found in the Heimat, in a natural environment as untouched as possible. At least that’s how it’s constructed. Sometimes it involves a village community, sometimes isolated alpine farmyards, but they are places where people can heal and get healthy – and without all the demands of daily life.

That is obviously particularly clear in times of crisis when things are open and up in the air – when it’s uncertain whether the world in which one lives will remain peaceful or whether in the next few years one will still have a job or house – or be healthy.

swissinfo.ch: Immigration is a big issue in Switzerland and Europe at the moment. Do you think that plays a role in the popularity of looking back to a time when not many people were foreign. There are rarely any non-white faces in these films…

I.T.: That could of course be a factor, but I don’t think – take this Heidi film – you can necessarily look at it just with a Heimat backdrop. The longing for a Heimat might well have something to do with people feeling threatened by immigrants. This could be justified or not: the vote [on February 9, 2014, in which Swiss voters put limits on immigration] showed that the areas with the fewest immigrants were the areas that were most afraid of them!

But Heimat films have perhaps other backgrounds. In particular with Heidi or Schellen-Ursli, I’d say people like making films of classics of children’s literature. Heidi is such an international classic that has already been filmed so many times – actually every generation has its own Heidi film.

swissinfo.ch: Are there differences between these films and the Heimatfilms of the 1950s and 1960s?

I.T.: Definitely. The films in the 1950s and 1960s were made under the impact of the Second World War, and people wanted to oppose this impression – of fear, threat and rubble landscapes – with healing nature and healing people, as it were. And for that reason in the Heimatfilms of the 1950s and 1960s the city-countryside conflict was greatly emphasised. The aim was always the nuclear family – women never had permanent jobs, children were never without direction and so on.

The new Heimatfilms are more concerned with contemporary problems, it’s noticeable that in the meantime the image of the family has changed – there’s not just the nuclear family but other family shapes. Gays and lesbians appear in the new Heimatfilms, companies go bankrupt, banks are blamed for farms which are collapsing. Current problems are woven in.

More

The little girl who conquered the big screen

With Heidi, things are obviously a bit different because it has this literary model and because it’s a children’s film like Schellen-Ursli, but in these ‘New Heimatfilms’ – and that’s what they call themselves – the divide between city and country isn’t underlined so much, at least cities are no longer demonised. Cities are busy and hectic and people are happy when they can leave them and go into the country, but it’s not the end of the world when they return!

In the new films, life is still simplistic and slightly idyllic and unpleasant things are glossed over, but not like they were in the 1950s and 1960s.

swissinfo.ch: Heidi has been filmed dozens of times. Why does she remain so popular?

I.T.: Heidi has a few stock themes: the relationship between town and country is frequently a subject in literature, orphans are a really popular theme as is getting healthy again in nature, the traumatised grandfather who is saved to a certain extent by his grandchild or guided back into society. This ‘saviour child’ is also a really popular motif – children who save their parents’ marriage or patch up the family again, right through to fantasy literature where children save the entire world!

There’s a whole list of motifs which pervade literature and which therefore don’t become unmodern or uninteresting. Regarding Heidi, that’s certainly important, but there’s also the fact that the Heidi books had already enjoyed considerable international success, and once a subject has established itself, it’s easy to jump onto this success.

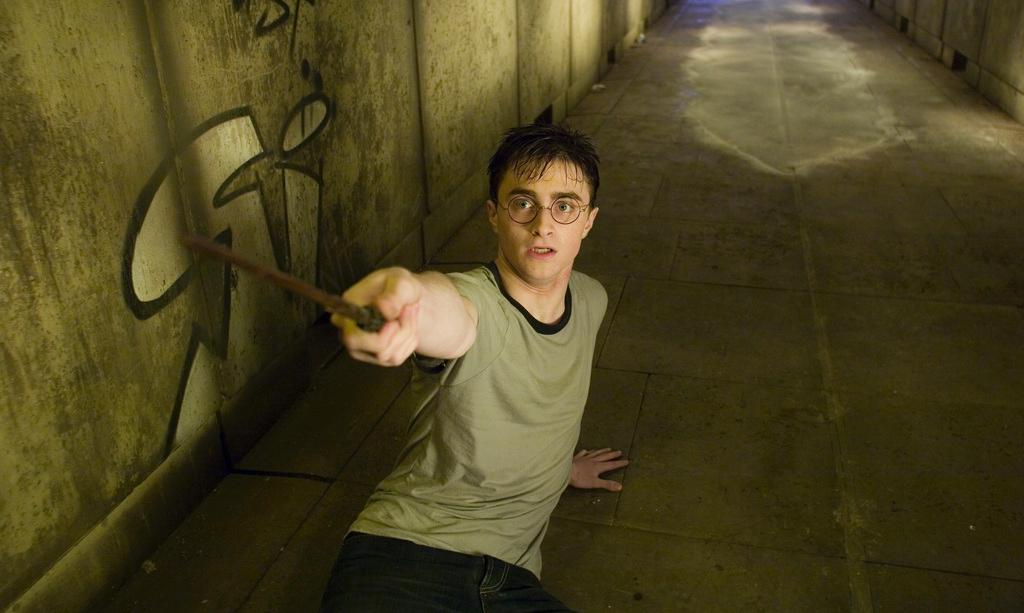

swissinfo.ch: You mentioned orphans. The list of famous literary orphans is huge: Peter Parker (Spider-Man), Annie, Tom Sawyer, Frodo Baggins, Oliver Twist, Pip in Great Expectations, Harry Potter, not to mention countless fairytale characters such as Cinderella. Why do writers – and readers – love orphans so much?

I.T.: Orphans obviously have an advantage for writers: they are not integrated into a family where it’s clear that parents dictate the rules but rather to a certain extent they have to fend for themselves. Usually they are not going to stay where they are forever – they are sort of in transit – everything is open and they have to forge new relationships and struggle through life. They are looking for a home and in this search have to prove themselves again and again in the face of setbacks. This situation alone gives the author loads of possibilities for exciting episodes or even for a real adventure structure.

The other thing is that orphans are good identification figures for young readers. Freud wrote that children often dream about being in the homes of other parents – they believe that their parents are not in fact their parents and that their real parents are socially better off – nobility, for example, or in any case not like their parents really are. This means that children can identify very well with these orphans, who are searching and who are ultimately capable of relationships with all types of people. They can sort of participate in the adventure that these orphans are experiencing – even if there’s suffering involved, as with Oliver Twist. He has to really put up with a lot before he discovers at the end that he’s a rich heir. But young readers like the chance to empathise and suffer with another child.

swissinfo.ch: Are you looking forward to the new Heidi film? What aspects will you find interesting?

I.T.: I’ll certainly end up watching it. In the book the grandfather character is very interesting because he had a problematic past and to a certain extent went through a trauma. In many film adaptations this is simply left out – right from the start he is nice to Heidi and looks forward to her visit. This aspect of his character is played down. Other versions make the grandfather’s story very central and it becomes about how the grandfather overcomes this trauma. It becomes a major storyline.

The role of the grandfather will depend on how critical of society this film is overall. In the 1960s it didn’t take long, also as part of the 1968 movement, for people to start criticising the Heidi films of the 1950s for being far too harmless and failing to portray the important issues of the book. Then in the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s there was a 26-episode television version which was told from a real social-historical perspective: it showed how hard living conditions were for people in the Alps; it showed poverty, how life revolved around work, that there were also serious health problems, loneliness, psychological issues and so on.

We’re once again going through a crisis, but it’s not particularly socially critical. It will be interesting to see whether the latest version will be idyllic or whether it manages to portray the subject matter in its complexity.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!