What future for the younger generation?

Youth unemployment is a major problem in Europe: in the European Union over 20 per cent of under-25s are affected, and in Spain and Greece it’s more than half. Yet in Switzerland it is just over three per cent.

Switzerland has had a good economic outlook, with employment on the rise, both before and just after the financial crisis. “And when employment rises, it is usually young people who benefit,” explained Serge Gaillard, of the State Secretariat of Economic Affairs (Seco).

But that is just a short-term factor, Gaillard, Seco’s head of labour directorate, told swissinfo.ch.

“In the long term, our dual education system – parallel training on the job and in vocational school – is one of our major strengths. Two-thirds of young people in Switzerland already start work at 16 or 17 and combine practical experience with classroom instruction. This system has worked well. Countries with this kind of dual education system tend to have lower rates of youth unemployment.”

Too many graduates

For sociologist Karl Haltiner, the academic director of Federal Youth Surveys, it is significant too that in Switzerland the difference in prestige between practical apprenticeships and secondary education is not very great, unlike in countries of southern Europe.

“Although the number of young people going to university is rising in this country too, we are still far from the situation in Italy where almost 30 per cent of people are university graduates,” he told swissinfo.ch.

A large number of these graduates later have to compete in a labour market which cannot absorb a lot of them. They are then forced to look for less qualified work “in order to find anything at all”.

Job protection

Haltiner is critical of the highly developed employment protection that workers enjoy in the EU countries with the highest rates of youth unemployment.

“This produces what you might call an ‘insider-outsider-market’. If someone has a job, is protected by a union agreement and as an ‘insider’ can hardly ever be laid off, then the ‘outsiders’ – mostly younger jobseekers – can find no jobs and are often shamelessly exploited as ‘trainees’.”

He pointed to the example of Italy, where labour law makes it impossible for companies with more than 15 employees to make layoffs even when the economic climate is unfavourable.

“Companies are hardly likely to hire new staff because they won’t be able to let them go again even in a downturn,” he said.

The Italian government of Mario Monti is currently trying to make these strong job protection provisions more flexible as part of its reform programme, but considerable opposition is coming from the unions.

The situation in Spain is similar to that in Italy. Problems in southern Europe are accentuated by the extreme cost-cutting approach adopted by governments and the general lack of growth, Haltiner says.

He contrasted these policies with the more flexible job protection legislation introduced in Germany a few years ago “which is contributing to the favourable economic situation with less unemployment and less youth unemployment”.

Solutions?

In order to stabilise or even to reduce the youth unemployment rate in Switzerland (3.2 per cent in March), two factors are likely to be decisive, according to Gaillard.

The first is “a balanced macro-economic situation, an economy that is not stagnating, and jobs”.

The second factor is the educational system, where as many young people as possible either complete secondary school graduation or an apprenticeship.

“Young people who don’t complete some kind of training are often jobless or even end up as welfare recipients,” said Gaillard. “So we must make sure there are training places available in sufficient quantity for our young people.”

For Europe the same prescription applies.

“These countries often have the dual problem that they are not competitive and are heavily in debt. It is very difficult to solve both of these problems at the same time, when you are stuck in a fixed currency area and can’t devalue. The second thing is to develop training approaches by which the young people can get their foot in the door of the working world as early as they can.”

Integrate, communicate

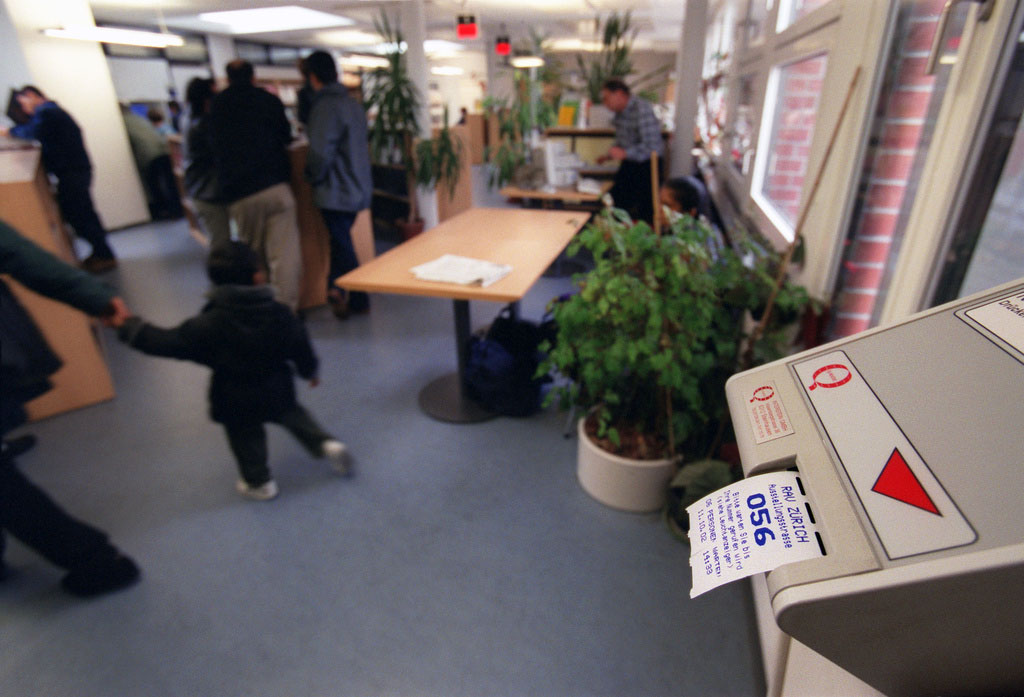

Claudia Menchini, director of the Bern job network of the Diaconis foundation, which tries to integrate jobless people back into the job market, warns that apprenticeships are not necessarily enough.

“When young people have completed an apprenticeship or training in Switzerland, basic employment experience is still lacking. The working world wants that, and so young people tend to get the short end of the stick,” she told swissinfo.ch.

In addition to technical knowledge, it is important in today’s labour market that employees commit themselves to the company and also be willing to take criticism, she pointed out.

“That is often hard for young adults, especially if they come from a family from another culture without much educational background and do not have the necessary support at home.”

Haltiner agrees that there can be a problem here.

“In Switzerland we need better integration of immigrant children as regards education, and better information for their parents about the training options.”

Motivation

Menchini often encounters a feeling of hopelessness among school leavers who fail to find an apprenticeship.

Those who don’t meet all the requirements of the working world, and who get caught up in a never-ending cycle – working, jobless, dole, working, jobless – often get to feel they have no future, she says.

But Haltiner is more optimistic. Youth questionnaires taken over 40 years show little change in the attitudes of most young adults: they put a high value on work and career.

“They are quite motivated and achievement-oriented, but it helps for them to know about the good job prospects out there.”

At 3.2% (March 2012) Switzerland has the lowest youth unemployment in Europe.

In the European Union it is over 20% (eurozone 21,6%; 27 countries of the EU 22,4%).

In Spain and Greece it is over 50% (50.5% and 50.4% respectively). In Bulgaria, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal and Slovakia, over 30% of under-25s are jobless.

Only in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands is youth unemployment less than 10%.

Worldwide it is 12.7%, a rising trend.

(Source: International Labour Office (ILO), 9.4.12).

According to estimates by the International Labour Organization (ILO), the number of jobless will increase to 204 million people worldwide in 2012. For 2013, it expects the figure to rise to 209 million.

“It seems likely that the economic situation this year will just get worse and that there will not be an upswing till 2013,” ILO deputy director-general Guy Ryder told the German newspaper Die Welt.

He said there were officially 27 million more unemployed than there were before the 2008 global financial crisis, but if those not registered in the statistics are taken into account, the figure is 56 million.

(Translated from German by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.