Chicago artist displays his ‘engaged practice’ with Black Madonnas

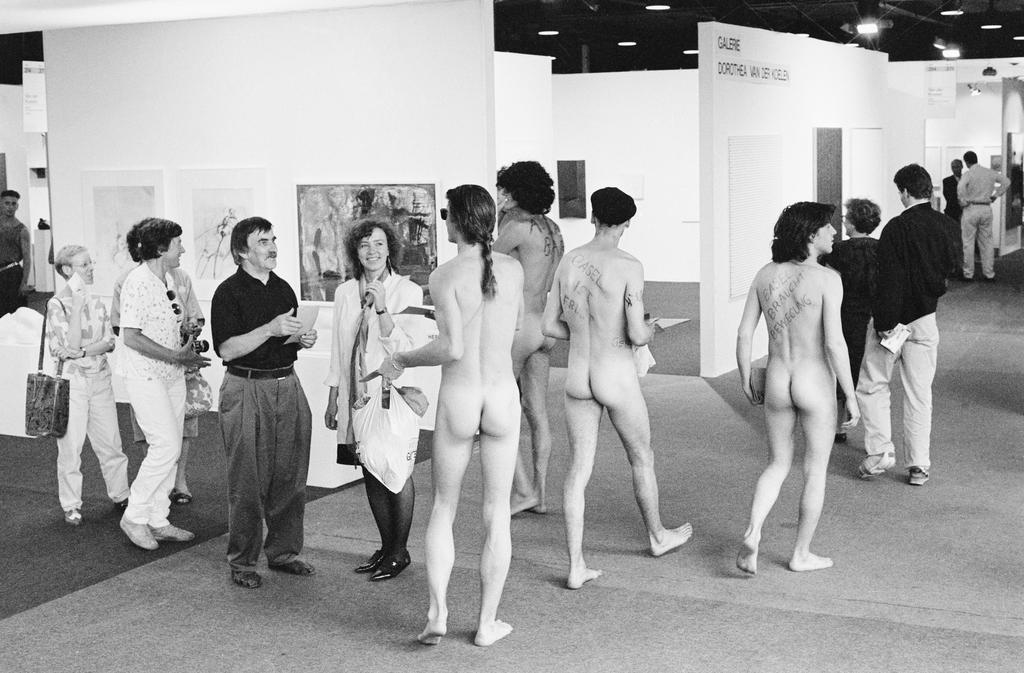

As a counterpoint to Art Basel – one of the most important arts fairs in the world – the fine arts museum of Basel is opening a large exhibition of US artist, activist, urban planner Theaster Gates: “Black Madonna”.

For the Kunstmuseum, Gates explores the cult of the “Black Madonna”,

showcasing new works made especially for the occasion of the exhibition as well as interactions with works from the collection of the Kunstmuseum Basel curated by the artist. Together with local and international partners, the artist will engage viewers in a series of live performances planned to last until the end of the show on October 21.

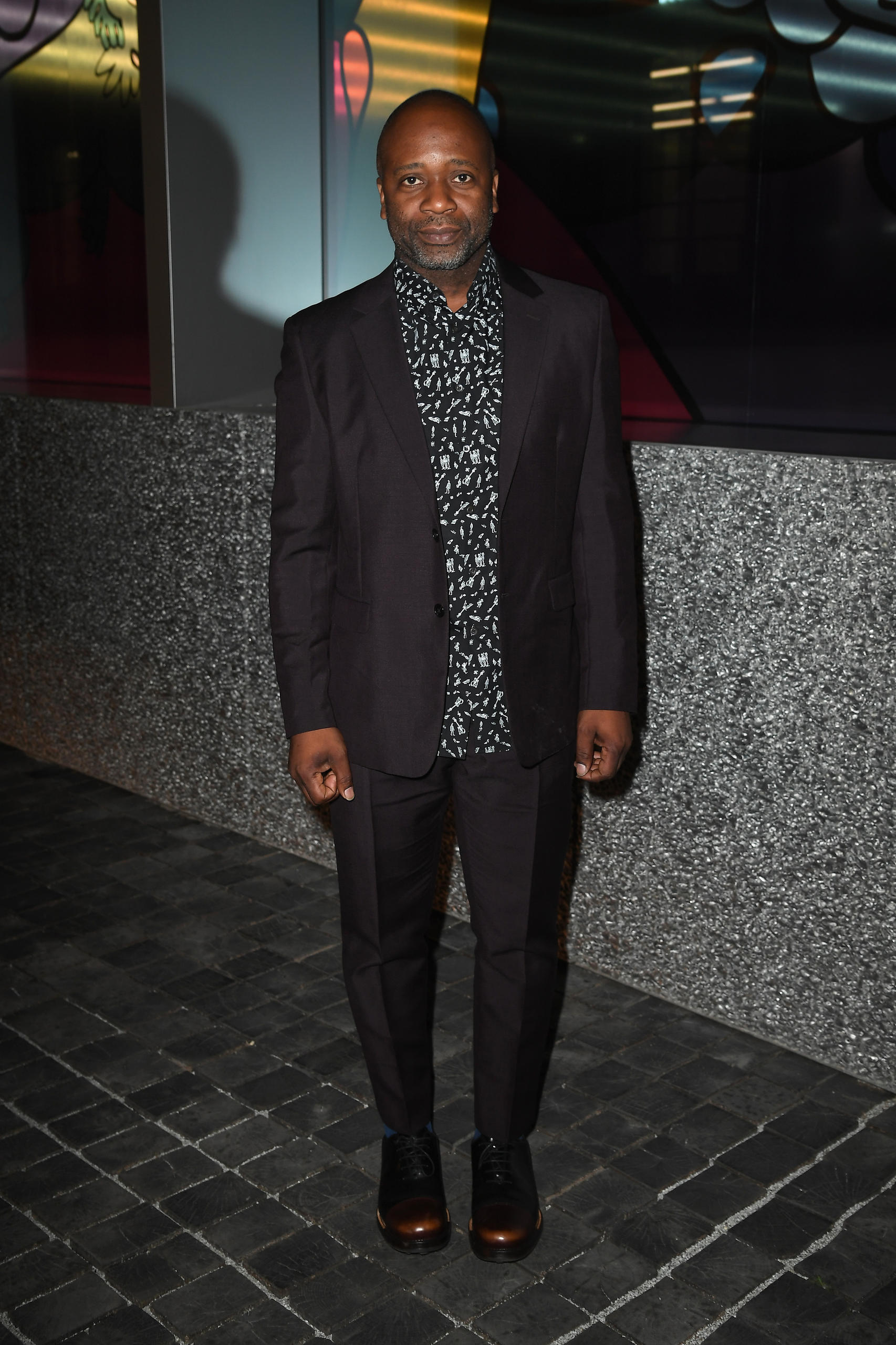

A few days before the opening, and at the request of swissinfo.ch, Damian Christinger, an independent curator and author based in Zurich, visited Gates in the middle of the exhibition’s montage.

The conversation

I enter the Kunstmuseum Basel Gegenwart by the backdoor. It is Monday, so the museum is closed, and the artist is busy assembling his exhibition “Black Madonna” – normally not ideal conditions for a conversation about religion, race, gender and revolution. But Theaster Gates is relaxed and excited about his upcoming show and I would soon understand why.

The entrance hall is dominated by a black sculpture of a Madonna – cast with tar – with a Baby Jesus in her lap, who is strangely missing one arm. Surrounding the life-sized sculpture there is a continuous bookshelf, mounted on eye height, supporting a half circle of 2500 books. They are all bound in black leather with gold lettering on the spine and seem to protect and venerate the Black Madonna at the same time.

Damian Christinger (swissinfo.ch): What kind of a library am I looking at, and why is Jesus missing an arm?

Theaster Gates: I work a lot with archives. I often buy whole collections of books or LP’s connected to black culture, and make them public, open them up for the everyday paople to be involved. It is unavoidable that there are doubles or even triplets of the same book when you bring different collections together. So I started to use them as a kind of raw material, a basis from which to work with. I took the title of the book as a starting point, sometimes just a word, sometimes an associative phrase, and started to play around with different combinations, thus creating poems by the titles on the back of the books, which I had then bound in black leather with the parts of the poem on the back in gold lettering. It would be great if the visitors read their individual poems aloud, creating a collective performance, a prayer-like atmosphere.

(He starts to read the words out aloud to me, putting emphasis on single words or phrases, sometimes whispering, then shouting)

Surely the nation can

Rugged cross

Jagged edge

Heavy burden

Paid and laid by she

Shemotherblack

Madonna laid down the law

She got the traction

Parish to Parish

From Poland to Detroit

Detroit to Atlanta

To Houston

Not only God of the Blacks

But mother of us all

swissinfo.ch: What about Baby Jesus with the one arm missing?

T.G.: The model for the cast was a key fob, which is used by a lot of people, and one of them was given to me, already in the state in which we see him here. I like the fact that he is vulnerable, protected by the Black Madonna. Were it hotter in here, the tar that she is made of would start to melt, changing the smooth surface.

swissinfo.ch: There seems to be a strong personal element in this show. One light installation with bathroom tiles on the ground is entitled “Bathroom Believer”.

T.G.: Yes, that is true, there are a lot of personal memories incorporated in this show. This is how I grew up, surrounded by a lot of strong black women and of course my mother, who used to lock herself up in the bathroom to pray, the only place she could find some rest from her kids.

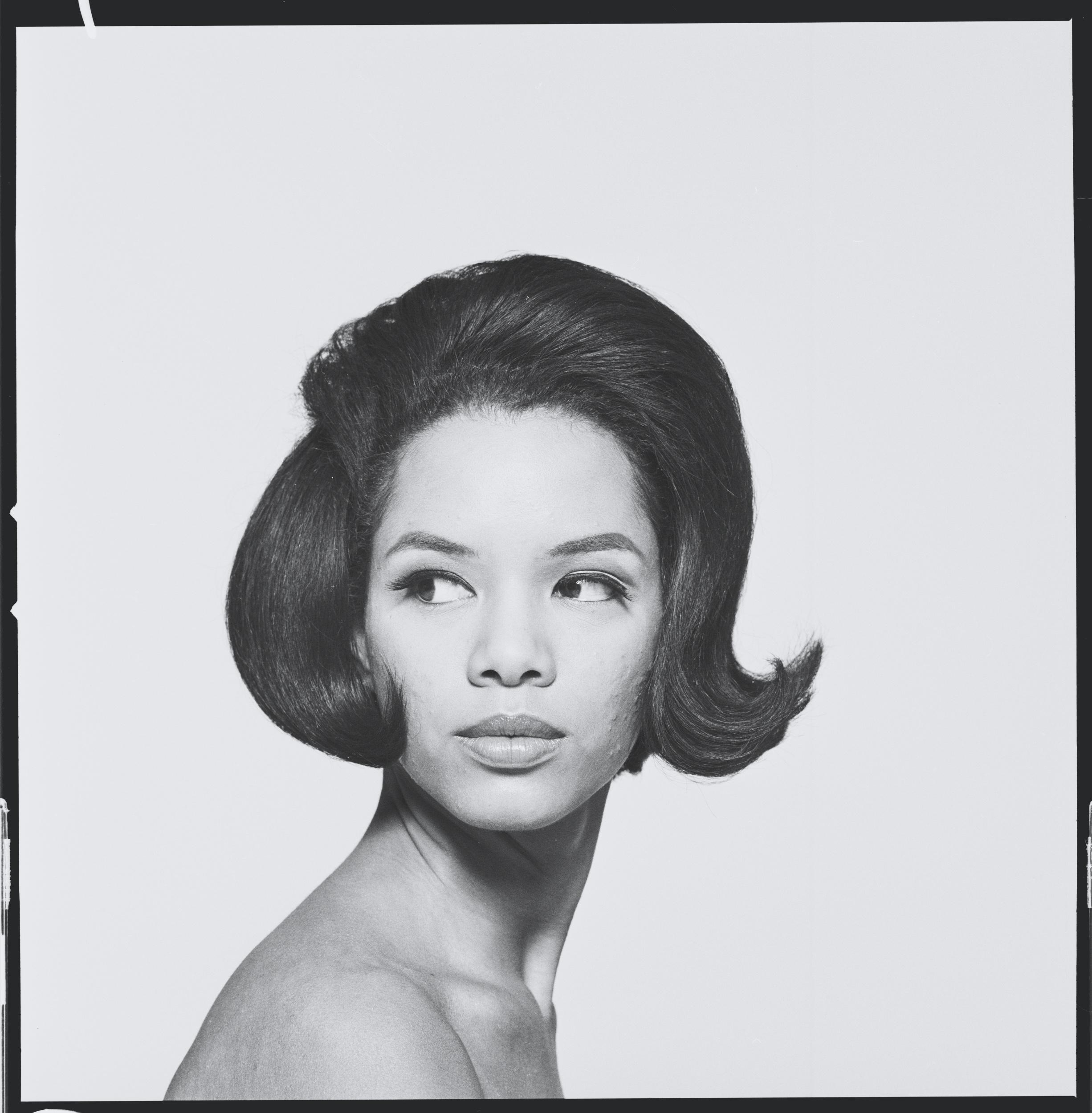

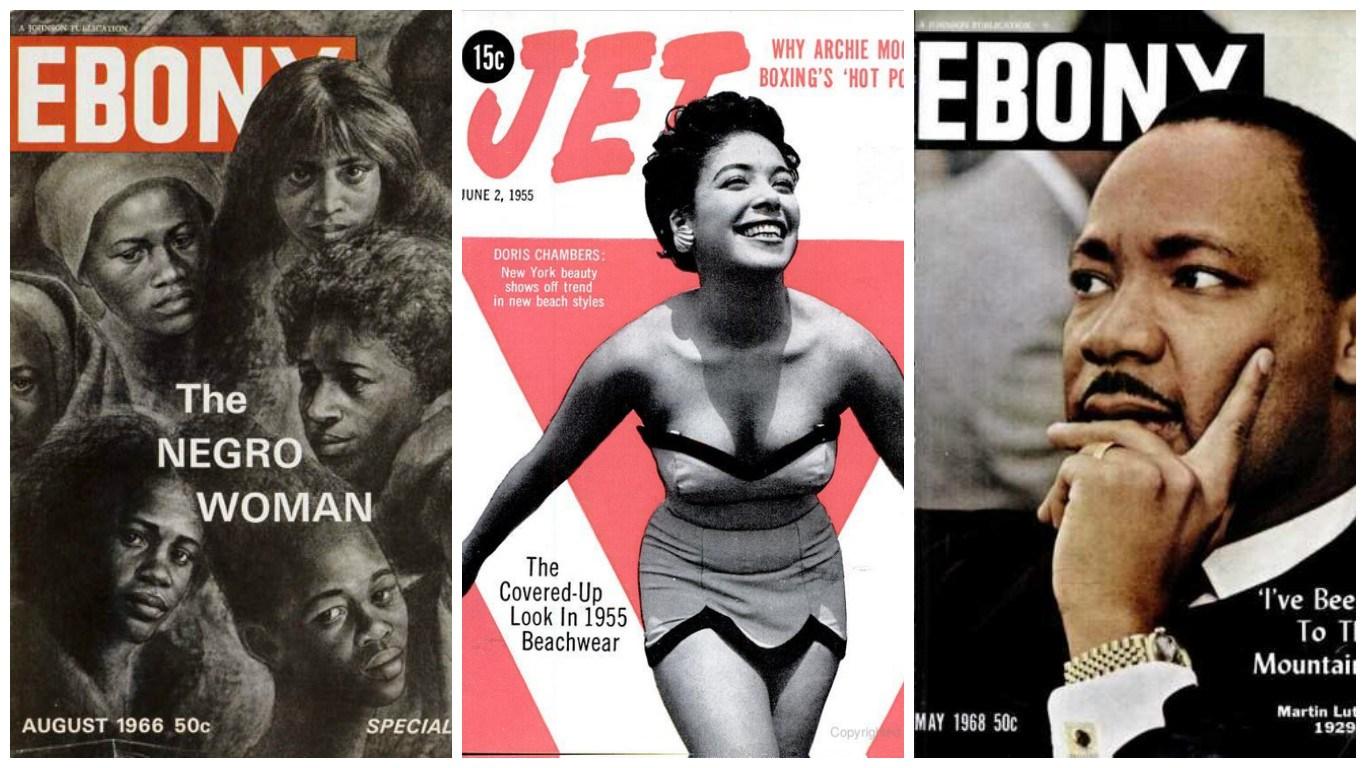

swissinfo.ch: At the same time there are a lot of references to African American Culture, turning pictures of women from the archive of the Johnson Publishing Company, which published “Ebony” and “Jet”, two of the most influential magazines for popular black culture, into posters. One of these posters with the slogan “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”External link [title of a song by Gil Scott-Heron, 1970] stands opposite to a screen with idyllic, advertisement-like films of African-American life in the 60s. Do you relate to W.E.B. Du Bois, who once wrote that “all art is propaganda and ever must be”?

T.G.: When I was 19, enrolled as an art student, I went to see some relatives in Detroit. That was the first time I visited “The Shrine of the Black Madonna” of the Pan-African Orthodox Christian Church. The church emphasizes that the survival of the black people and their salvation are dependent on the working for the good of the community and on rejecting individualism. To this end the church seeks to build a nation within a nation where African-Americans can create institutions to promote their political, economic, social and psychological well-being.

Inside the church, there is a painting by Glenton Dowdell, from 1967, depicting a “Black Madonna with Child”. This visit was very influential for my work. This painting is not what is called “high art”, it is rough and powerful, speaking directly to the congregation and aimed at the masses; it is indeed propaganda. Churches like these have very strong roots within revolutionary ideas, dreams of a black revolution.

I think it is important for a European public to realize that most people have a land of origin as a starting point for their identity. Because of Slavery, we don’t have that luxury. So these churches sought such an identity and went back to Africa, to Egypt and other places, claimed that black people were witnesses to the murder of Jesus Christ, who was decidedly non-white, by the Romans, and that these origins are the seeds of a coming revolution in the US. This gives the figure of the Black Madonna a different meaning than in Europe. Here in Switzerland the Black Madonna was venerated for a variety of reasons, one of them the belief that a Black Madonna was more authentic, linked to Byzantium.

swissinfo.ch: In the Musei Capitolini in Rome there is a sculpture of “Artemis of Ephesos”. It is a Roman copy from the 2nd century of a Greek sculpture from the 2nd century B.C. This goddess was thought of as having raised Zeus in a cave on honey. The Roman copy has a body made of white marble, but the face and hands are blackened bronze. When Maerten van Hemskeerck, whose painting of a Madonna you have chosen from the collection of the Kunstmuseum Basel as a juxtaposition for your show, depicted the Artemis Temple of Ephesos, he modeled the building after “Santa Maria Novella” in Florence. Thus linking the “Black Madonna” of the Romans to his contemporary cult of Mother Mary.

T.G.: What you are saying is that the Madonna cult in Europe has pre-Christian roots. So do we of course. Egypt may figure so prominently in black churches for different reasons, one of the aspects of Egyptian culture that always fascinated me, is the fact that they didn’t have words for black or light skinned, you were an Egyptian or not, that was what mattered, nothing else. But this convergence of different ideas in a common world history fascinates me and I think that is one of the reasons that the figure of the Black Madonna is so relevant. It is connecting different cultural spheres through female aspects, which is a given, that cannot be stressed enough.

The “engaged practice” of Theaster Gates

It is hard to categorize Theaster Gates, born in Chicago in 1973, simply as an artist. Maybe the best definition was penned by the Tate Gallery in London: “Theaster Gates is a social practice installation artist. He began his career studying urban planning, and took a joint masters in religion, ceramics and city design. Partly thanks to these influences he now brings activism, project managing and urban planning to his work.”

In plain English, that means that Gates’ artistic work is not meant to decorate anyone’s walls. He’s committed to the revitalisation of poor neighbourhoods and of Afro-American archives, engaging his viewers and communities in debate, collaboration and social interaction.

More

Art in Basel is much more than Art Basel

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.