Battle begins against drones and killer robots

The intensive use of drones by the Obama administration is feeding a wave of protest and criticism which reaches Geneva next week when a coalition of NGOs will call for a halt to the race to build technology for autonomous killing robots.

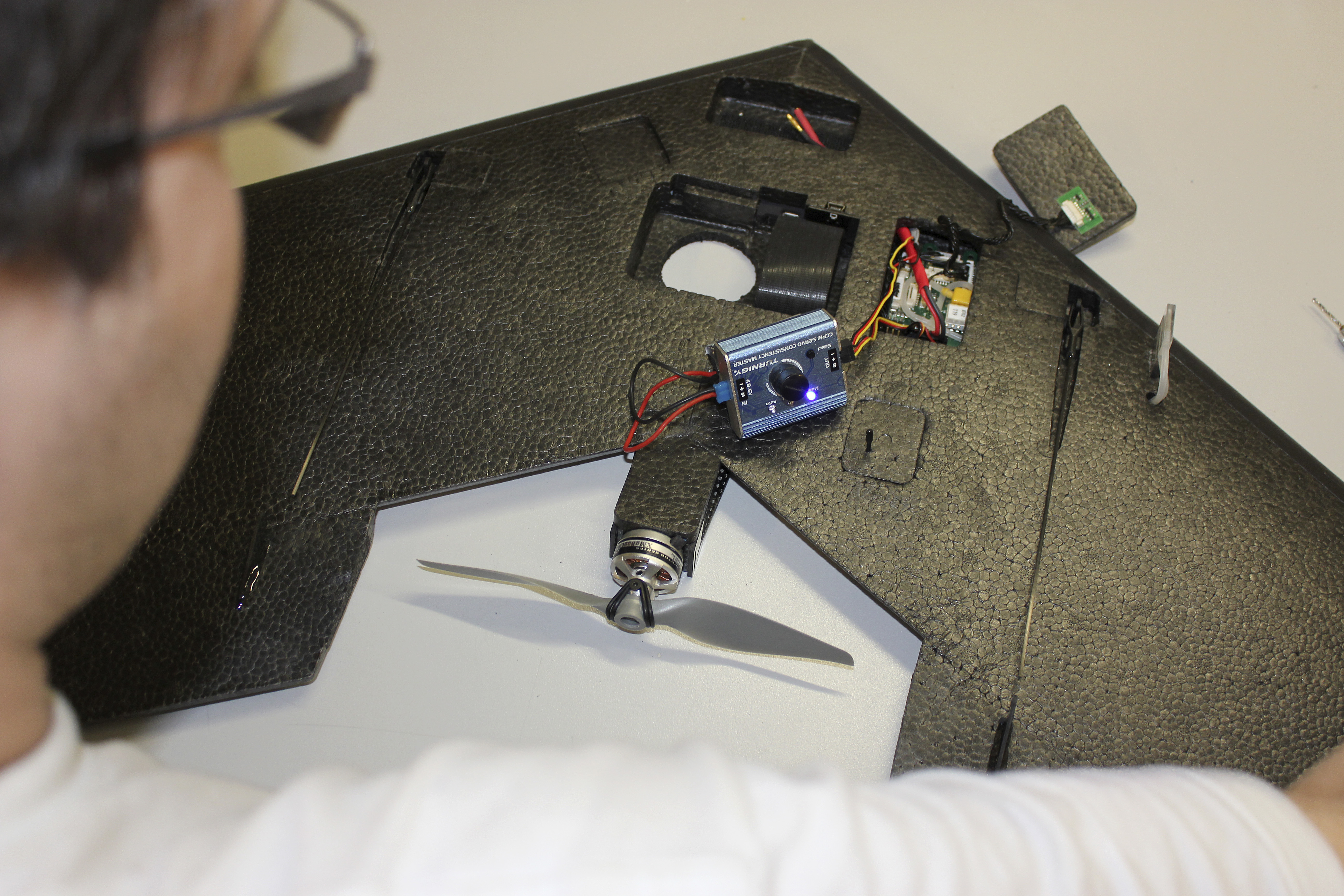

The increasing robotisation of military hardware is a new and worrying development that the defenders of human rights and guardians of the Geneva Conventions are attempting to curb. Campaigners are talking two distinct approaches.

The first concerns the use of drones in the international fight against the elusive al-Qaida – a programme launched after the September 11 attacks and heavily used since the arrival to power of United States President Barack Obama.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a non-profit organisation based in London, estimated that drone attacks between 2004 and 2013 caused between 2,500 and 3,000 deaths (including hundreds of civilians and close to 200 children) and more than 1,000 injuries in Pakistan alone.

Pressure on Obama

To determine whether the Geneva Conventions have been violated, the Human Rights Council tasked British lawyer Ben Emmerson, United Nations special rapporteur on counter-terrorism and human rights, to investigate the issue.

According to Emmerson, the central goal of this investigation is to evaluate if the drone attacks have caused a disproportionate number of civilian casualties, which is contrary to existing international humanitarian law.

Emmerson is due to present the results of his investigation in September at the 68th UN General Assembly.

Under pressure from public opinion, the Obama administration is weighing up the problem, and there is talk of moving the programme for the elimination of terrorist groups from the CIA to the slightly more transparent Pentagon, according to the Daily Beast (a news website associated with Newsweek).

“This transfer is still just a rumour. Nothing official has been announced. But this change goes in the direction of our demands,” Andrea Prasow, of Human Rights Watch, told swissinfo.ch.

In parallel, Christof Heyns, UN expert on extra-judicial executions, summary or arbitrary, will present a new report to the 23rd session of the Human Rights Council in Geneva on May 29. This document, centred on “lethal autonomous robots”, calls for an international moratorium on the development of these instruments of war.

More

Drones – innovation or threat to society?

Preventive action

On the fringes of the session, the campaign ‘Stop Killer Robots’, officially launched in London in April by a coalition of NGOs, is organising a press conference at the European headquarters of the UN to call for the ban on such arms.

They aim to follow a process similar to that which led to the convention on the banning of anti-personnel mines, in force since 1999. Except this time – as a first – the ban being sought concerns weapons which do not yet exist.

“Semi-automatic systems like drones are controlled and piloted by human beings, albeit at a distance,” Andrea Bianchi, professor at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva told swissinfo.ch.

“Through interpretation it is possible to apply the existing rules of international humanitarian law. In contrast, completely autonomous combat systems distance man more and more from the machine.”

More

Successful takeoff for Swiss commercial drones

Humans out of the loop

In his report, Heyns makes a similar analysis: “Given the increased pace of warfare, humans have in some respects become the weakest link in the military arsenal and are thus being taken out of the decision-making loop.”

However, security expert Alexandre Vautravers believes we are far from this point. “You have to distinguish between the sensational and the systems which are being assisted or which have a certain autonomy.”

“Today we have systems which can organise between themselves, how to fly in formation to provide radio coverage by relay, or a complete field of vision of a certain area.

The Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) has laboratories which are working on this kind of system,” he said.

“But the Terminator is not about to arrive. All the more so as the military budgets of the countries most advanced in this area, beginning with the US, have been revised downwards.”

In his report, Heyns claims it is urgent to regulate. “Technology is developing exponentially, and it is impossible to predict the future confidently. As a result, it is almost impossible to determine how close we are to fully autonomous robots that are ready for use.”

“Military documents of a number of States describe air, ground and marine robotic weapons development programmes at various stages of autonomy. Large amounts of money are allocated for their development.”

Perpetual war

One thing is certain. The nature of war has changed since the advent of drones at the beginning of the 1990s.

“The experience with UCAVs [unmanned combat air vehicles] has shown that this type of military technology finds its way with ease into situations outside recognised battlefields,” Heyns’ report says.

Heyns is concerned about the danger that the world will be seen as a single, large and perpetual battlefield.

“The nature of robotic development generally makes it a difficult subject of regulation, especially in the area of weapons control. Furthermore, there is significant continuity between military and non-military technologies.”

“The same robotic platforms can have civilian as well as military applications, and can be deployed for non-lethal purposes or be equipped with lethal capability.”

Which is why Bianchi is calling for a serious debate about these questions.

“It would be good to put together the different actors in this dossier – not only the ICRC [International Committee of the Red Cross], the UN and the states but also the scientists and the experts in international humanitarian law – for the most honest possible reflection.”

“The advancement of technology is such that international law cannot allow itself to be left behind,” said Bianchi.

This is also the first effect that can be seen from the campaign Stop Killer Robots: the opening of a public debate on a subject until now the preserve of experts and the end users, the military.

In an interview published on the website of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) on May 10, its president Peter Maurer explains how and under what conditions international humanitarian law is applicable to the use of armed drones.

After recalling the main principles of international humanitarian law such as the distinction between civilian and military and the proportionality required in the use of force, Maurer stresses the potential interest of a weapon like a drone.

“From the perspective of international humanitarian law, any weapon that makes it possible to carry out more precise attacks, and helps avoid or minimise incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, or damage to civilian objects, should be given preference over weapons that do not.”

Maurer adds this point on the use of armed drones outside war zones. “If and when drones are used in situations where there is no armed conflict, it is the relevant national law, and international human rights law with its standards on law enforcement, that apply, not international humanitarian law.”

“The question is whether lethal force may lawfully be used against such a person and under what legal framework. Opinions diverge. The ICRC holds the view that international humanitarian law would not be applicable in such a situation, meaning that this person should not be considered a legitimate target under the laws of war.”

“Advising otherwise would mean that the whole world is potentially a battlefield and that people moving around the world could be legitimate targets under international humanitarian law wherever they might be.”

Source: ICRC

The Swiss Army plans to buy new unarmed observation drones to replace those which have been used since 2001, ADS 95 Ranger drones.

According to Armasuisse, the federal competence centre for procurement of complex systems and equipment, two drones systems made by Israeli manufacturers Aerospace Industries Ltd (IAI) and Elbit Systems (Elbit) are currently being evaluated.

“The evaluation should be completed by mid-2014, after which it will be possible to make a choice between the two systems,” Armasuisse spokesman François Furer told swissinfo.ch.

For its part, the state-owned aerospace defence firm RUAG, is taking part in the nEUROn programme run by the French Dassault Aviation, a prototype of partly-autonomous combat drone.

(Adapted from French by Clare O’Dea)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.