New legislation on restitution of dictators’ assets

Switzerland has been one of the favourite hiding places for the ill-gotten gains of the world’s dictators. The Swiss government now wants to facilitate the freezing and restitution of this money with a law that will pioneer new standards internationally.

Yet even new standards will not resolve all the problems, as has become apparent in the wake of the Arab Spring.

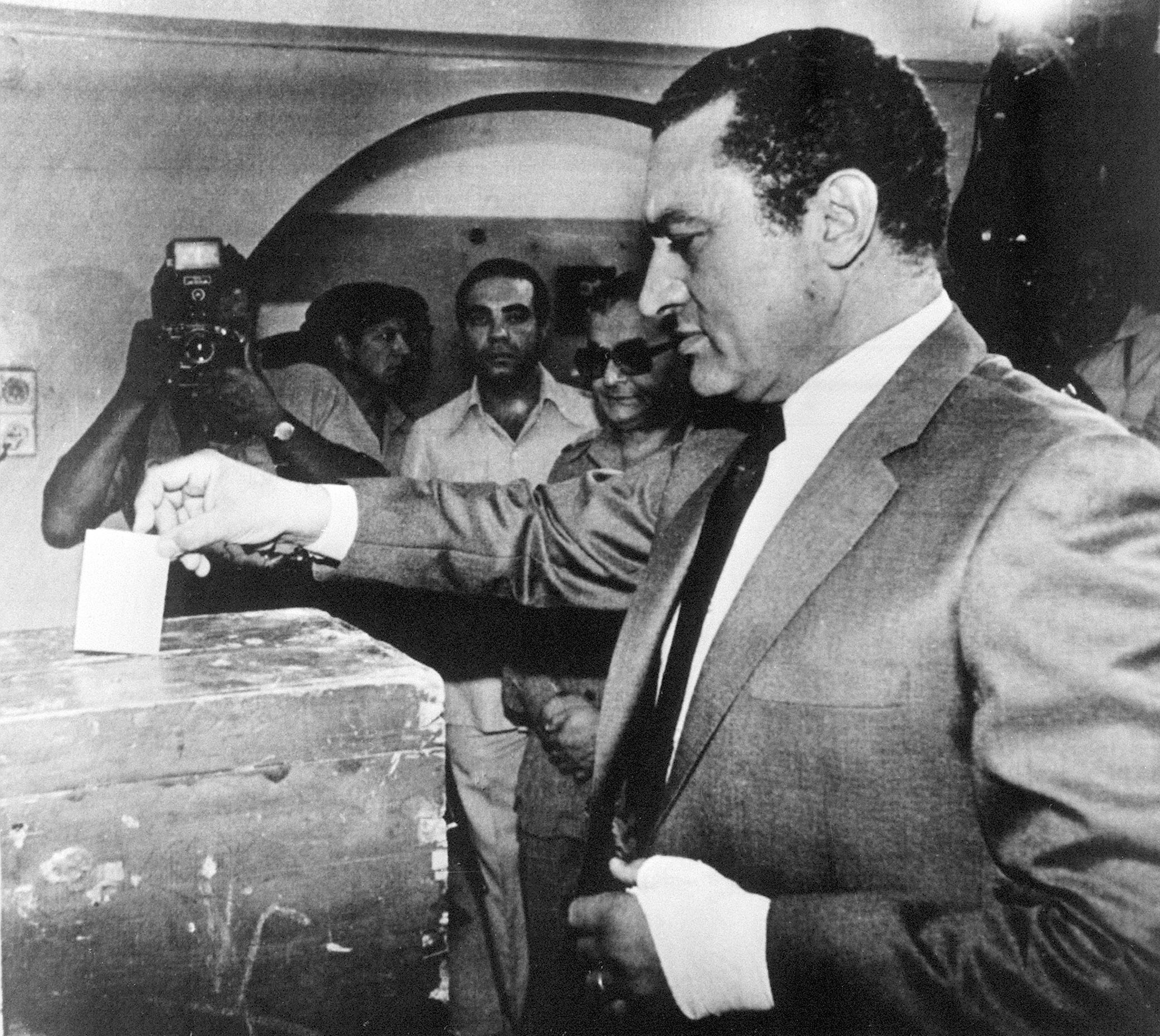

“In 2011, Switzerland was the first country to freeze the assets of Ben Ali and Mubarak after their fall in Tunisia and Egypt. But instead of plaudits, there was criticism because they had their money in Switzerland in the first place,” notes Rebecca Garcia, spokesperson for the Swiss Bankers Association.

In spite of efforts made by the Swiss government since the 1980s to freeze what have become known as “dictators’ assets” and return them to the countries they were stolen from, international public opinion still has a rather negative perception of Switzerland in this regard because of the long list of despots who have hidden money in Swiss banks. Following the Arab Spring it emerged that about a billion francs had been deposited in recent decades in Switzerland by the rulers of Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Syria.

The Swiss government is aware of this problem. In May this year it put forward for consultation a draft bill on the “Freezing and Restitution of Assets of Politically Exposed Persons obtained by Unlawful Means” which aims to strengthen the current provisions. The political parties and relevant organisations have until mid-September to discuss the bill, which could become a model internationally, as experts from the World Bank and other institutions have noted.

Timeline: Dictators’ funds in Swiss banks

Burden of proof

The law being considered would widen the government’s powers to freeze assets as a precautionary measure to prevent their being spirited out of the country again. Up till now, assets were frozen only where the country concerned put in a request for judicial assistance or if there was a total collapse of state structures preventing a country from making such a request.

“In many cases, as in Egypt, there has not been a total collapse of state structures, but neither is it possible to collaborate on a regular procedure of judicial assistance: the people in power change rapidly and the federal government does not know who it should be talking to,” explained Mark Herkenrath, a specialist in international finance at Alliance Sud, which is made up of six of the main Swiss non-governmental organisations.

To freeze the assets of the dictators overthrown during the Arab Spring, the government had several times to invoke an emergency procedure provided by the Federal Constitution. This practice is, however, supposed to be for exceptional cases.

Another important point: the bill provides for the inversion of the burden of proof. It will no longer be necessary for Switzerland or the countries involved, such as Egypt or Tunisia, to show that the assets of a Mubarak or a Ben Ali come from illegal activity. Now the dictators will have to prove that their assets were come by honestly.

According to estimates by the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), every year some 850 billion dollars are transferred illegally from developing countries to tax havens elsewhere.

This sum greatly exceeds the contributions of governments, international organisations and NGOs to development aid in poorer countries – which amounts to about 130 billion dollars a year.

According to estimates by the World Bank, every year between 20 and 40 billion dollars are removed from developing countries by means of unlawful appropriation, corruption and abuse of power by leaders and public officials.

Vicious circle

If the new standards proposed by the government are voted into law, Switzerland will in future collaborate more actively in investigations with the countries that have been defrauded. It could provide information on bank accounts even before receiving a request for judicial assistance.

“Up until now it has been a vicious circle: without a request for judicial assistance the countries involved cannot get this information. But without the information, they cannot usually make a detailed request for judicial assistance,” Herkenrath pointed out.

While supporting the bill on the whole, the Swiss bankers have some reservations on this particular point.

“This information should be supplied only if the receiving country provides democratic guarantees and has legal structures in place. Otherwise there is a risk of exposing people to action that could arbitrarily put their rights and their lives at risk,” said Garcia.

The new legislation also provides explicitly that the money returned be used to improve the living conditions of the population and strengthen the rule of law in the country in question. The Swiss government clearly wants to avoid seeing this money go back on the merry-go-round of corruption and organised crime.

Switzerland was first faced with the problem of dictators’ assets in 1986, when Philippines strongman Ferdinand Marcos was driven from office.

Since then assets of several other corrupt leaders hidden in Swiss banks have come to light. They include Mobutu Sese Seko (Zaire, now renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo), Jean-Claude Duvalier (Haiti), Sani Abacha (Nigeria), Hosni Mubarak (Egypt), Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali (Tunisia), and Moammar Gaddafi (Libya).

Over the past 20 years, Switzerland has restored CHF1.7 billion to countries pillaged by their rulers. In the same period the world figure for such restitution was CHF5 billion, according to the World Bank.

Political parties disagree

The bill, which will be brought before parliament next year, is already encountering opposition from the parties of the centre and right. “Switzerland does not need new legislation, as we are already far in advance of other countries. Often, we do too much, as happened in the case of Egypt: Mubarak’s money gets frozen, but we don’t know who to give it to,” claims Luzi Stamm of the rightwing Swiss People’s Party.

For the left, on the other hand, the legislation means a great step forward, but is still not enough. The new standards lay down in detail how stolen assets are to be frozen and restored to their rightful owners, but they do not solve the problem of how these assets are accepted for deposit in Swiss banks. Dictators’ money is almost always the result of corruption, illegal appropriation and other abuses of power, claims the centre-left Social Democratic Party. “The CHF700 million ($770 million) Mubarak had deposited in Switzerland did not become illegal just when he was overthrown.”

According to the government, freezing the assets of dictators still in power is not feasible. Political leaders usually enjoy legal immunity and Switzerland has to guarantee the rule of law to all countries.

“The decision to freeze assets can only bear fruit if a judicial assistance procedure for their restitution can then be opened. But this usually cannot happen before a change of power,” explained Pierre-Alain Eltschinger, a spokesman for the Swiss foreign ministry.

Due diligence

“It is up to the banks under their obligation of due diligence to investigate thoroughly before entering on business relationships with clients. This is especially so in the case of politically exposed persons,” he added.

But due diligence is not always adequately exercised, according to Herkenrath . “One gets the impression that banks do no more than the minimum provided for by law – and that the supervisory authority does no more than routinely approve what the banks are doing, without asking too much from them.”

These criticisms are rejected by the Swiss Bankers Association.

“We have to notify suspicious cases under the law against money laundering,” Garcia insisted. “But it is not up to the banks to decide if a political leader is abusing his power. Especially when you consider that many heads of state fall into disgrace only after their overthrow. Mubarak and Gaddafi were being hugged and kissed by European leaders just a few weeks before their political downfall.”

(Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.