A host of unburied issues: the Swiss political agenda in 2019

Some political monsters of the past lie dormant under the winter snow, but they are sure to rise again in spring. What can Switzerland expect from politics in 2019?

To look into the future, we first need to take stock of what has gone before. And due to the often glacial pace of Swiss politics, plenty of major political projects were left unfinished in 2018. They are sure to come back to haunt us. Here is part one of our annual review and forecast.

When voters reject two major reform packages within a short period, what do you do? Mix up the ingredients and send them back in one big package to make the proposals look more appetising? This is what the Swiss government is trying with its combined taxation and pension funding proposal, which comes after two major 2018 upsets.

In February, voters rejected the Corporate Tax Reform III; a government proposal to align tax legislation with new international standards, thus avoiding punitive sanctions. A few months later citizens also turned down the Old Age Pensions 2020 proposal – an attempt to adapt the social security system to the economic and social challenges of the future.

With the new mega-package, so, government and parliament are hoping they can square the circle. The goals are the same: to make corporate taxation comply with the new standards, and ensure ongoing funding – at least in the medium-term – for the social security system.

The referendum campaign to oppose the package will be fought by the youth wings of the Greens and the conservative right People’s Party; if they manage to secure the necessary 50,000 signatures, voters will go to the polls on May 19.

Much ado about nothing: that would be a good title for at least the first act of the Revision of CO2 legislation, debated in the House of Representatives during the winter session. But with one major difference from Shakespeare’s play: given the impending signs of doom on the climate front, there was nothing to laugh about.

The House, tasked with implementing Switzerland’s pledges under the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, spent several days discussing the bill. Proposals came from right and left; there was discussion as to how and where greenhouse gas emissions might be reduced, such as by taxing airline tickets or putting up the price of petrol.

At the end of the debate, however, part of the political centre stood up and walked out, and the House ended up rejecting the government’s proposal.

The right, led by the Swiss People’s Party (currently the party with the most popular nationwide support), refused to back any proposal that it viewed as harmful to the country’s economy. On the left, not even the red-green camp managed to support the revised legislation, which it saw as insufficiently ambitious and watered down.

In 2019, the bill will go to the Senate, and the debate will start all over again.

Meanwhile, politicians will not be the only ones to have their say in 2019. Signatures are already being collected for a “glacier initiative”, which will call for an end to the use of fossil fuels by 2050. If it gets enough support it will eventually go to voters, who may yet play the leading role in the next act, rather than simply providing the chorus.

In this particular game, the ball is back in the federal court – namely, the Federal Administrative Court in St Gallen. Yet whatever decision the judges arrive at in 2019, it will not solve the problem definitively.

In June 2017 a razor-thin majority of 137 had decided that the French-speaking town of Moutier, hitherto part of canton Bern where German is spoken by a large majority, should join French-speaking canton Jura. But the jubilation that this electoral decision would bring the long-simmering issue to an end turned out to be short-lived.

Already on the day of the vote, Bern loyalists had complained about irregularities in the electoral register. And when it emerged that some Jura supporters were said to have moved to live in Moutier for a while before moving away again, an investigation was opened.

And in November 2018, after a 17-month investigation, the government of Bern decided to declare the result of the vote invalid. Moutier’s municipal council appealed this decision to the Federal Administrative Court, but a decision is not expected anytime soon. Lengthy legal interventions need to be heard, and a re-run of the vote is unlikely in the foreseeable future. The appeals could go all the way to the European Court in Strasbourg.

The fires of the Jura conflict will be stoked for at least another year.

Due to mushrooming health care costs, the nation’s insurance premiums rise each year with the dependability of a Swiss watch. Indeed, every September, citizens wonder not whether their premiums will go up, but by how much.

The reasons for this vary. For one, medical science continues to make progress, and this leads to more and more costly drugs, operations and treatments. In 2011 the Swiss doctor’s magazine warned: “If modern medicine goes on progressing at the current rate, we will all soon be old, sick and broke.”

Other factors are an ageing population, immigration, an increase in chronic diseases, and a high concentration of hospitals and doctors in Switzerland. There are also inefficiencies and disincentives within the Swiss healthcare system. Swiss people also have high expectations of their health care system and are not prepared to tolerate a reduction of basic coverage.

Four people’s initiatives to curb the rise in costs or else to cut down insurance premiums have been announced, while some are already gathering signatures. All are to be watched throughout 2019.

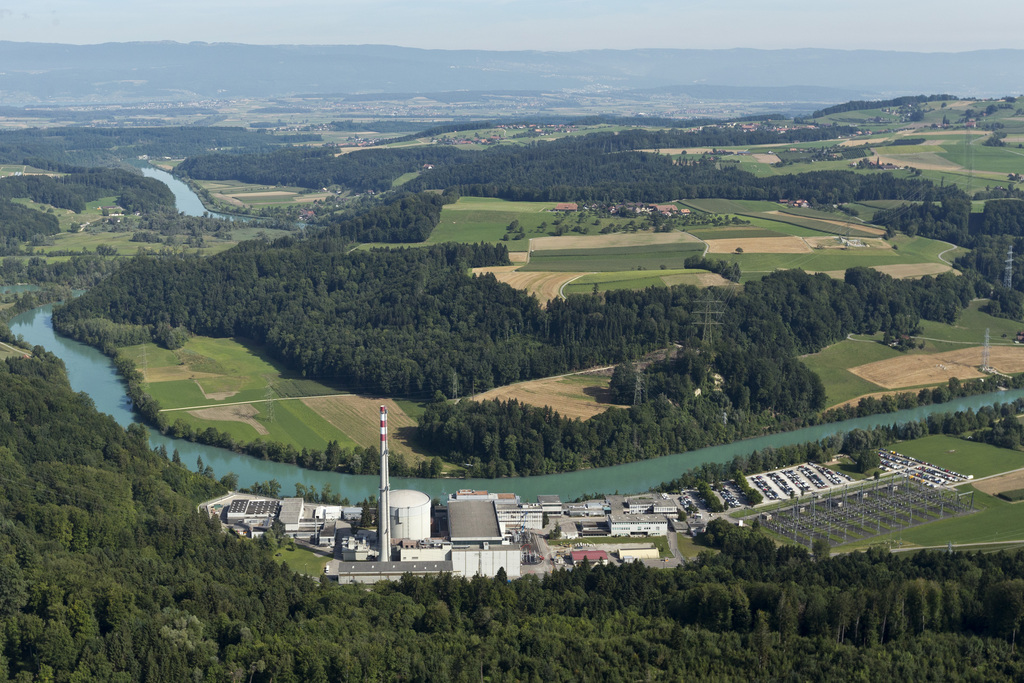

One particular monster from the past which has troubled Switzerland for a long time will be shuffling towards its grave in 2019: on December 20 this year the nuclear power station at Mühleberg, 15 kilometres from the capital city Bern, will be shut down for good.

The nuclear reactor has been operating since 1972 and is one of five in Switzerland; it generates about 5% of the electricity used in the country.

Once the fuel rods are cooled and neutralised, they will be placed in intermediate storage. Then the next phase begins, that of dismantling the entire facility, which will last until 2030. The price tag for the entire process is expected to be CHF927 million ($942 million), with a further CHF1.43 billion needed to dispose of leftover radioactive waste.

Translated from German by Terence MacNamee, swissinfo.ch

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.