Paranal’s giant eye peers into the universe

Perched at 2,637 metres above sea level in the driest desert on earth, there is an other-worldly feel to the modern astronomical observatory at Cerro Paranal.

swissinfo.ch visited the hi-tech facilities in northern Chile, run by the European Southern Observatory intergovernmental research organisation – of which Switzerland is a member – to find out why they provide such ideal conditions for professional star-gazers.

It’s half past seven in the evening when the most advanced optical observatory in the world – the Very Large Telescope (VLT) – begins work and the doors of the four buildings that house the facility slowly open.

The VLT is actually a combination of four gigantic telescopes with 8.2-metre diameter lenses and four additional telescopes each measuring 1.8 metres in diameter.

“One of the most fascinating characteristics is that these instruments are able to work together, allowing us to obtain extremely high resolution images. It’s a unique concept,” Swiss scientist Ueli Weilenmann, deputy director of the Paranal and La Silla observatories, told swissinfo.ch.

By combining them to work as an optical interferometer, the instruments are powerful enough to be able to pick out car-sized objects on the moon. Such a feat would normally require a conventional telescope 200 metres in diameter and 16 metres long.

“To do so the light of the telescopes has to travel through underground tunnels to the interferometry laboratory where the light rays meet,” said Weilenmann.

The VTL has been used in a number of scientific breakthroughs, such as proving the existence of a supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way, the first image of an exoplanet and the most distant gamma-ray bursts on record.

Comfy conditions

Some 40 astronomers work shifts at Paranal in teams of ten or 12. They are supported by assistants, technicians, maintenance staff, administrative personnel, cleaners and cooks, totalling 120 people.

The Paranal facilities also include a modern apartment complex, a small clinic, gym, restaurant and heated swimming pool to make the stay more pleasant for those working in the middle of a desert 130 kilometres from the nearest city, Antofagasta.

“Astronomers come for a few days and then return home, but continue their research,” said Weilenmann.

This is the case of Steffen Mieske, who lives in Santiago, and travels periodically to Paranal.

A day’s work

The young astronomer and coordinator of the ESO Chile research group is preparing to start his day that should finish as the sun comes up.

“Tonight I have to work on the “Paranal-isation” of the teams,” he explains.

This involves adjusting the instruments to the characteristics and demands of the observatory – a complex process that can take months or even years.

Everything is managed from the main control room. In modern astronomy experts do not directly touch the telescopes but control them remotely using automatic systems.

“They receive images and spectra via networked computers in the control room and then are able to observe and interpret the data,” explained Weilenmann.

Ideal climate

Paranal is a magnificent location for star-gazing, said the Zurich-born scientist who started work at the observatory in 2004.

“As well as its ultra-modern technology, it is located in a place with excellent climatic conditions. The Humboldt ocean current produces a temperature inversion phenomenon: on the coast the air is always wet and cool, while it is dry and hot at altitude. That makes the sky very clear; 90 per cent of the time it is cloudless,” he said.

On top of its financial contributions to the ESO, Switzerland participates via research at Geneva University.

“Experts from the university built a spectrograph known as Harps which brought them fame when searching for extra-solar planets, and which was used at the La Silla Observatory [in northern Chile]. There is currently a new spectrograph project here called Espresso. In a few years we will have a new machine to discover exoplanets,” he said.

Basic questions

Knowing where we came from and where we are heading are some of the most basic questions in astronomy.

“In ancient times science was essential for survival; knowing the movement of the planets and the moon allowed us to determine the right moment to plant and to develop a calendar. Although this has changed, man is still interested in understanding how the universe evolved and whether life exists on other planets,” he commented.

Weilenmann believes that in the coming years we will get much closer to answering these questions.

“For reasons of probability we have to assume that life did not only evolve on our planet. Given the sheer number of stars in the universe, it would be egotistical to think that we are the only ones that exist. Of course you have to wonder what kind of life exists on other planets, and the distances in the universe are so vast that it’s highly unlikely that we will actually meet,” he added.

“But if instruments that are capable of looking millions of years into the past and also into the future allow us to dream about one day finding a sign of life – why not?”

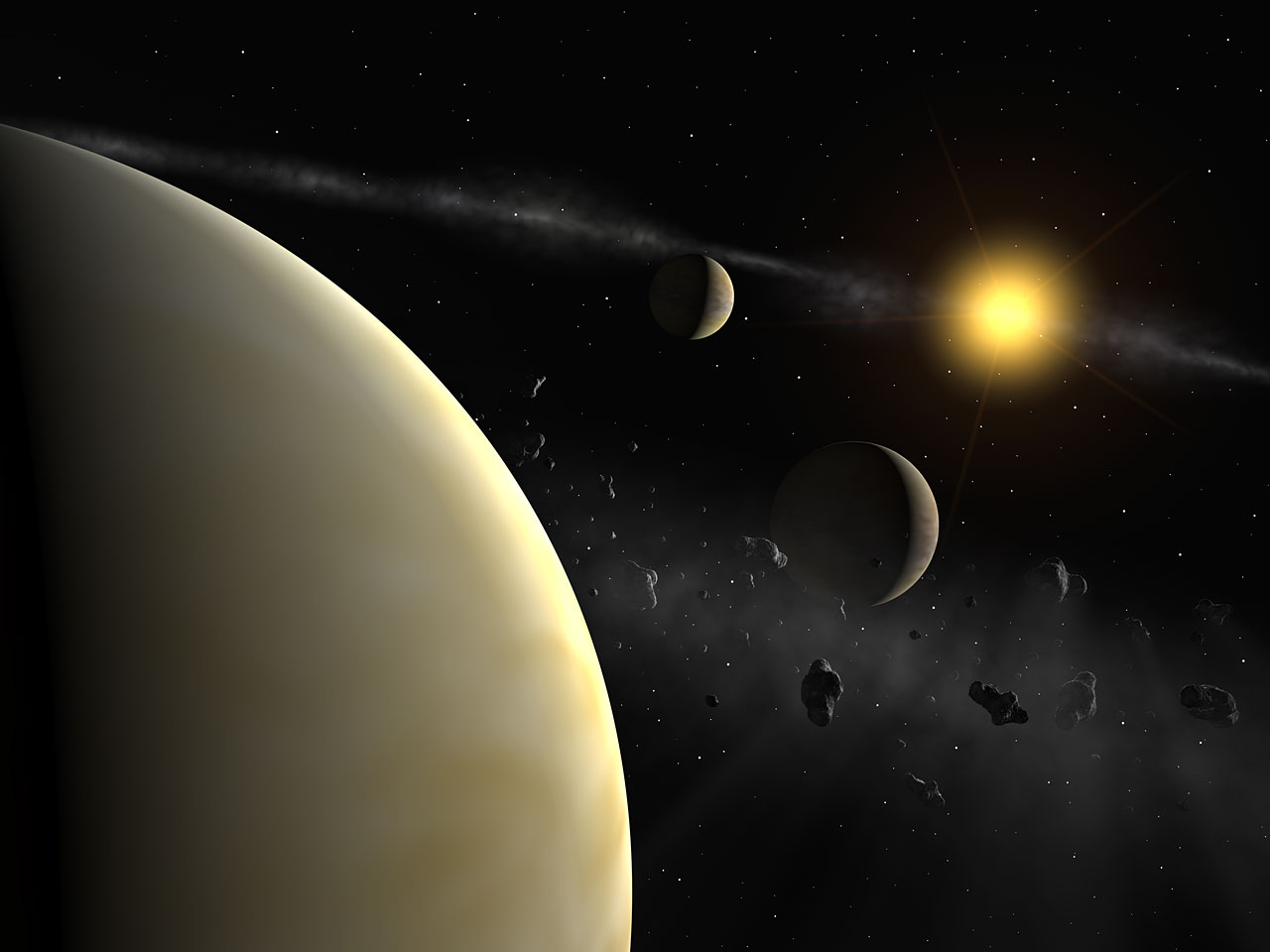

Exoplanets are planets outside our solar system.

The first exoplanet was discovered by Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz from the Geneva Observatory in 1995.

As of September 13, 2011, a total of 677 exoplanets have been identified, although none can be seen by telescope. They can only be detected indirectly.

The overwhelming majority of exoplanets found so far are so-called “hot Jupiters”: large gas planets orbiting close to their star.

However, in 2007 Mayor and fellow astronomer Stéphane Udry discovered the first Earth-sized exoplanet, lying 20.5 light years or 120 trillion miles away, with a mass five times that of our planet, which is regarded as a possible candidate for sustaining life.

Udry’s team announced the discovery of another potentially life-supporting planet 36 light years away in 2011.

Created in 1962, ESO is an intergovernmental astronomy research organisation supported by 15 member states, including Switzerland.

The observatory is situated in the Chilean Andes: when it was set up, all other major telescopes were in the northern hemisphere.

It offers state-of-the-art research facilities and access to the southern sky.

It has built and operated some of the most advanced telescopes in the world.

They include the New Technology Telescope (NTT), the Very Large Telescope (VLT) and the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT), a 42-metre diameter instrument.

Harps is attached to the ESO 3.6 m telescope at the observatory.

(Translated from Spanish by Simon Bradley)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.