Swiss debate allowing government spyware

The Swiss parliament must decide if it will allow government spyware programmes to infiltrate the computers of criminals. The practice is controversial, with some experts viewing it as a double-edged sword that could also be turned against ordinary citizens.

“Until ten years ago it would have been impossible to imagine that governments of democratically-run countries would develop computer viruses that would be deployed against other democratic countries or even their own citizens. Yet exactly this is happening today,” said Mikko Hypponen, one of the foremost computer security experts in the world, at the 2014 Insomni’hack, an annual conference on computer security that took place in Geneva in March.

The internet has “turned into a gigantic surveillance machine”, he said.

According to secret documents revealed by former CIA officer Edward Snowden and published in mid-March, the United States National Security Agency (NSA) wanted to infect millions of computers with malicious programmes, also known as malware.

Hypponen, a Finnish computer scientist who is head of F-Secure, a digital security company, stressed the US is not the only country using government spyware. He also pointed a finger at China, Germany, Russia and Sweden.

And Switzerland? The secret service has never used spyware, said Jürg Bühler, the deputy director of the Swiss Federal Intelligence Service (FIS), in an interview with Swiss public television.

On the other hand, the Federal Office of Police has done so, more than once, which has spurred considerable debate – also because the use of such spying software is not yet regulated within a clear legal framework.

New law

The Swiss government intends to fill this gap with a new federal law on the monitoring of postal and telecommunications traffic.

The text of the law, still subject to approval by the House of Representatives – the Senate has already done so – allows spy software to infiltrate computers, smart phones or other mobile devices under certain conditions.

Technological developments in recent years, above all on the internet, have made it increasingly difficult to monitor telecommunications in connection with serious crimes, the government stressed.

Conventional methods of classical espionage, such as phone tapping, are ineffective in the face of encrypted communications systems such as Skype, for example. This kind of software is thus needed, it is argued, for the government to hold its own.

The potential of such computer programmes is enormous, Paolo Attivissimo, an expert on new technologies, told swissinfo.ch. “You can collect every kind of information.”

More

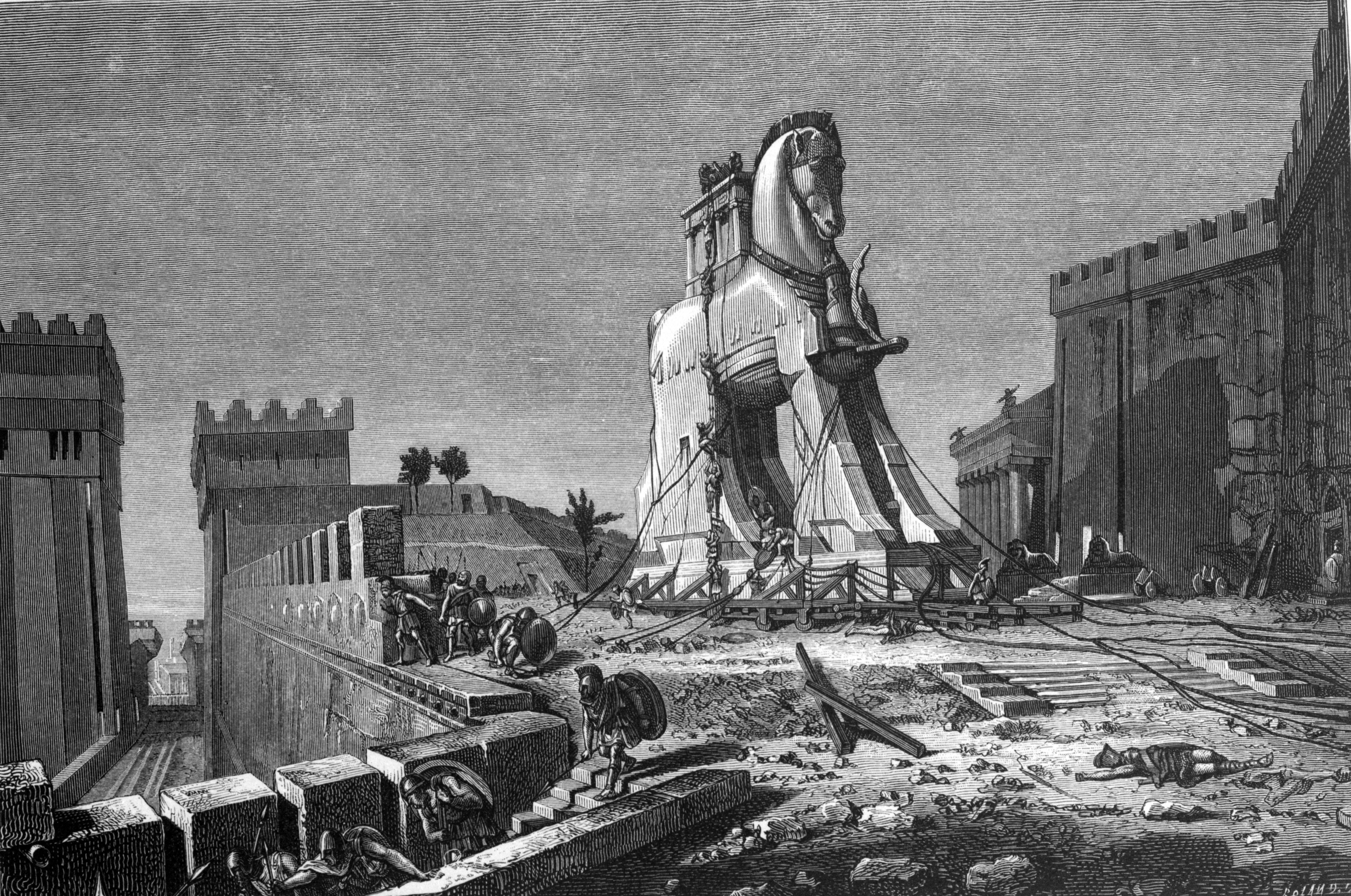

The tricks of a Trojan

Privacy fears

The new law, which has been under review since 2010, remains controversial.

“We criticise the American monitoring programme Prism, but Switzerland does the same thing,” Green Party parliamentarian Balthasar Glättli told the newspaper Le Temps.

The president of the Swiss Pirate Party, Alexis Roussel, sees spyware programmes as “a clear violation of the private sphere”.

In the view of Attivissimo, the idea of dispersing a government-virus programme is dangerous for the security of the entire Internet.

“How should a company that produces antivirus programmes behave towards a governmental spyware? Should they ignore it, or block it and protect the user? A huge dilemma,” he said.

On this point Hypponen of F-Secure takes a clear stance. “The harmful programmes of governments, regardless of who created them, will be fought,” states the website of the antivirus manufacturer, noting that R2D2, a government spyware, was actually utilised by various German states.

In Switzerland the use of government spyware for the purpose of surveillance is not regulated on a clear legal basis. The new federal law on the monitoring of post and telecommunications traffic allows the use of such spyware on computers and other mobile devices for various reasons.

With this software, the contents of encrypted communication can be revealed (email, internet telephony) and information about the sender and receiver can be collected. However, the law excludes an online search of the computer and the monitoring of the premises using a webcam and microphones.

According to the wording of the law, the police may rely on government spyware only to prove serious crimes (murder, human trafficking, terrorist financing, etc.) or to locate missing or fleeing people.

In March 2014 a revision was adopted by a large majority of the Senate. The House of Representatives’ Committee for Legal Affairs will first examine the dossier in June.

The act as a whole is very controversial. Various associations that are involved with digital issues, and the Green Party and the Swiss Pirate Party, have already announced that they will launch a referendum should parliament pass the law.

Laws which have been passed by parliament can be challenged by the public in a “referendum”. For a referendum to take place, 50,000 signatures must be gathered within 100 days of the publication of a decree. In a nationwide vote, a referendum needs only a majority of votes.

Possible criminal reaction

If a malicious software is detected by anti-virus programmes, someone could then study it and create a version to be used for criminal purposes, said Attivissimo. “As far as I am aware there have not been any such cases but such a scenario is quite possible.”

In the event that a manufacturer of an antivirus programme were to be asked to ignore the malicious software and then do so, it would create a vulnerability in all computer systems of the country being protected by this programme.

“A hacker could then use the same product in the knowledge that he would not be caught. The introduction of a virus increases the vulnerability of many computers rather than the security of a country.”

In response to a question from swissinfo.ch, the Federal Office of Police clarified that government spyware would not damage a computer system or its security mechanisms.

Even if the office knew that a computer expert could identify and analyse this type of software, it considers the risk of abuse low. The reason is that malware with functionality that far exceeds that of government spyware can easily be found and purchased on the internet at low cost.

Lawyers as key holders

Stéphane Koch, a specialist in economic intelligence, sees other problems in the use of spyware by governments.

“We are not protected against unfair human behaviour: A police officer or an employee of a company could develop such malware and use it for personal purposes,” he told swissinfo.ch.

The outsourcing of data and skills is common to these technologies, but in actual fact this should not be the case, said Koch, who is a member of the Internet Society, an international non-profit organisation which wants the internet to be open to everyone. “The more people who work on a project, the greater the risk of abuse.”

Unlawful interference, Koch explained, occurs not only in the manipulation of malware, but also during the transmission of the collected data or during storage on servers or in data centres, which are often located abroad.

Ruben Unteregger, a computer scientist who was involved with the R2D2 programming, is of the opinion that there is no company in Switzerland with the necessary skills to develop such software from scratch using their own resources.

“So you would have to rely on the big international players that supply their products to the whole world,” he explained in an interview with the online newspaper watson.ch.

What, then, should be done? To equip oneself with a double-edged sword, or forego a means that holds great potential? According to Koch, one could keep tight control over government spyware with use of a few safeguards.

“Activity would only be possible with ‘keys’ that just a few people have access to – for example, lawyers. This way it would be possible to prove when and by whom the virus programmes were activated.”

Switzerland has resorted to monitoring software to spy on the computers of suspects. This happened in at least four cases, according to confirmation by the Swiss Justice Ministry in October 2011. The operations, which were ordered by the Federal Prosecutor’s Office and authorised by the Swiss Federal Court, were used in the fight against terrorism.

According to the Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) newspaper the federal authorities monitored the email and telephone communications of the Zurich left-wing activist Andrea Stauffacher from January to April 2008. The NZZ wrote that the computer programme was supplied by the German company Digitask at a cost of €26, 000 (around CHF31,000 or $35,000).

Trojan horse programmes have also been used at the cantonal level. In 2007 the Canton of Zug police used it in the course of a drug investigation. In 2011 the prosecutor of the Canton of Vaud tasked a specialised Swiss firm with developing a spyware for the computer of a paedophile, which led to the arrest of the suspect.

(Translated by Kathleen Peters)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.