Questioning of UBS financier in China rattles private banking

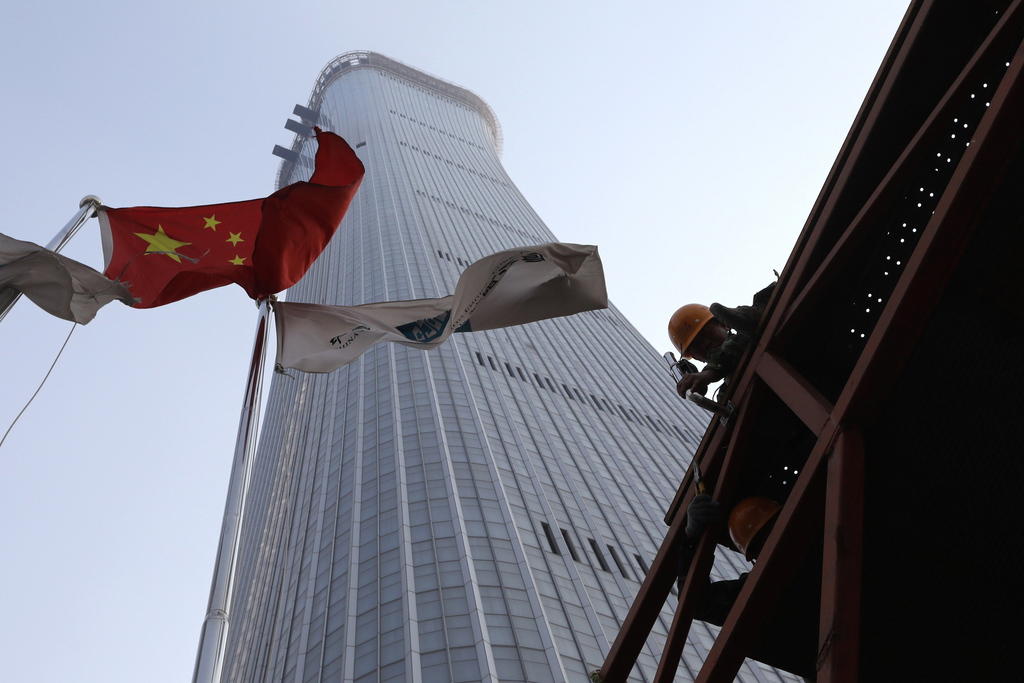

Asia’s fast-growing private banking sector has been shaken by the news that a UBS banker visiting China has been told by the authorities not to leave the country, casting a shadow over the opportunity presented by China’s large and expanding pool of billionaires.

The Singapore-based banker, who had travelled to Beijing to meet clients, has been asked to answer questions regarding an unspecified matter, spurring a warning from UBS to its private banking staff to delay travel to China.

Neither the Swiss bank nor the Chinese government gave details of the questioning, but Beijing has been mounting fierce campaigns to restrict capital flight, curb corruption and tackle tax evasion by its citizens.

More

Financial Times

External linkUBS, one of a few global banks running an onshore wealth management business in China, has since rescinded its travel warning. “The situation has happened in the past to other institutions; we took temporary measures [on travel] to see what was going on, and within 24 hours lifted the ban. Now we know the situation was nothing to do with the bank or with her,” said Sergio Ermotti, chief executive, on Thursday.

Chinese billionaires

More

UBS repeals China travel warning to employees

China has outpaced most other large economies in recent years in the rising number of its billionaires, and private wealth management for Chinese citizens is an attractive proposition for international banks that are struggling to grow their other business lines in the country.

The Swiss bank is Asia’s top wealth manager with $383bn in assets under management, followed by Citigroup at $256bn and Credit Suisse at $202bn, according to Asian Private Banker.

It remains unclear whether the reason for keeping the UBS banker in China is personal or professional. Yet a string of banks including Citi and BNP Paribas have asked their private bankers to reconsider China travel.

“I would imagine anybody heading up a private banking team [in Hong Kong or Singapore] must be quaking in their boots, thinking ‘What are we going to do?’,” said one senior banker in the region. “All the private banks are investing a hell of a lot of money in China at the moment.”

Others detained

This is not the first time a private banker has faced scrutiny by authorities in China, which is estimated to have 1.3m so-called “high net worth individuals”, a number exceeded only by the US, Japan and Germany. A Singaporean financier for Standard Chartered was detained, and later released, by Chinese police in 2012 as part of an investigation into alleged financial crimes by a wealthy client.

Bankers and other business people are already concerned that their communications are monitored by the Chinese authorities.

“I don’t have WhatsApp or WeChat, and I’m very careful with my communications,” said a person with years of experience in the industry, asking not to be named.

China’s onshore private banking industry is just over a decade old and has, since its inception in 2007, been viewed with some suspicion by regulators, said one industry veteran. The onshore private banking business has grown from nothing into an industry worth several hundred billion dollars in that short time, making it hard for regulators to keep up.

Michael Benz, former global head of private banking at StanChart and now senior adviser to management consultancy Synpulse, said he thought it unlikely — despite the shock felt by the private banks — that they would formally change their China strategies, because to do so would suggest they might have defied the mainland’s regulators in the past.

Chinese regulations on private banking are implemented sporadically and unpredictably, bankers said, and it is common to defy the rules in soliciting Chinese clients.

Business restrictions

Private bankers are not allowed to solicit orders for offshore investment products aimed at Chinese clients while in mainland China, but the practice is permitted outside. There are plenty of grey areas, however. “When is it that you talk about a product and when is it a more generic investment discussion? Sometimes it’s difficult to draw the line,” said Mr Benz.

Chinese banks are involved in the private wealth business too. State-owned China Construction Bank had Rmb940bn ($135bn) in private banking assets at the end of 2017, an increase of a fifth on the year before. The bank claims more than 67,600 clients each with a net worth of more than Rmb10m.

The number of foreign financiers travelling to the mainland has surged in recent years as private banks have focused on expanding their China business. Mr Benz said the chances were that as competition intensified some bankers crossed the line or upset the regulators. “[The UBS case] is certainly a reminder to watch out,” he added.

The UBS news comes as an economic slowdown in China, an escalating Sino-US trade war and a weakening currency are pushing more wealthy Chinese to avoid tax and take money out of the country in defiance of President Xi Jinping’s attempts to curb the outflows.

Close monitoring

Pressure for such individuals to diversify their investments outside China has mounted following the 2015 stock market crash and the slowing of the domestic property market.

Earlier this month Fan Bingbing, China’s highest paid actress, was fined Rmb479m for tax evasion after suddenly vanishing from the public eye for several months, in the most high-profile disappearance in recent years. And last year billionaire Xiao Jianhua was abducted by mainland Chinese agents from the Four Seasons hotel in the heart of Hong Kong and has not been seen in public since.

Both foreign and Chinese banks have been closely monitored over the facilitation of transfers of private wealth outside of the country, and some domestic banks have already been warned about such activity, said the private banking veteran.

One common scheme that has been the subject of a crackdown in recent years by China’s foreign exchange watchdog involves a client depositing cash onshore and being credited with the same amount offshore in Hong Kong or other locations outside the mainland. This business carries high penalties for anyone caught breaking the rules.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2018

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.