Neuroscience joins psychiatry on the couch

Swiss neuroscientist Pierre Magistretti talks to swissinfo.ch about Sigmund Freud, brain “glue” and why you should learn to play a musical instrument.

The director of the Brain Mind Institute at the Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne is leading a major new national research project, “Synapsy”, into the neurobiological mechanisms behind mental and cognitive disorders.

The research, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation and launched at the beginning of October, aims to bring the two disciplines closer together, shedding light on the origins of certain illnesses and helping train the next generation of psychiatrists.

swissinfo.ch: Why are there so few links between neuroscience and psychiatry after all these years?

Pierre Magistretti: This is quite strange, but there are historical reasons. At the end of the 19th century and start of the 20th century psychiatrists were very often neurobiologists. Aloïs Alzheimer was a psychiatrist working with a microscope who carried out autopsies on patients and looked at brains using his microscope.

Freud was a neurologist who wanted to find the biological origins of the psyche. But there were simply no tools available. He therefore developed a theory based on clinical medicine, which became so appealing that entire generations of psychiatrists somehow forgot that the psyche was based on what happens in the brain.

Then in the 1950s and 60s we discovered antidepressants and antipsychotic drugs by chance. Antidepressants come from a molecule used against the tuberculosis germ; people noticed that it put patients in a good mood. The emergence of all these molecules allowed patients to be treated even if they didn’t really cure them, and among psychiatrists biology was reduced to the level of psychopharmacology.

Another reason is the limited knowledge we had about how the brain works. At the end of the 1970s, when I began my research, the gap between what we knew and clinical psychiatry was huge.

swissinfo.ch: How much more do we know now about how our brain functions?

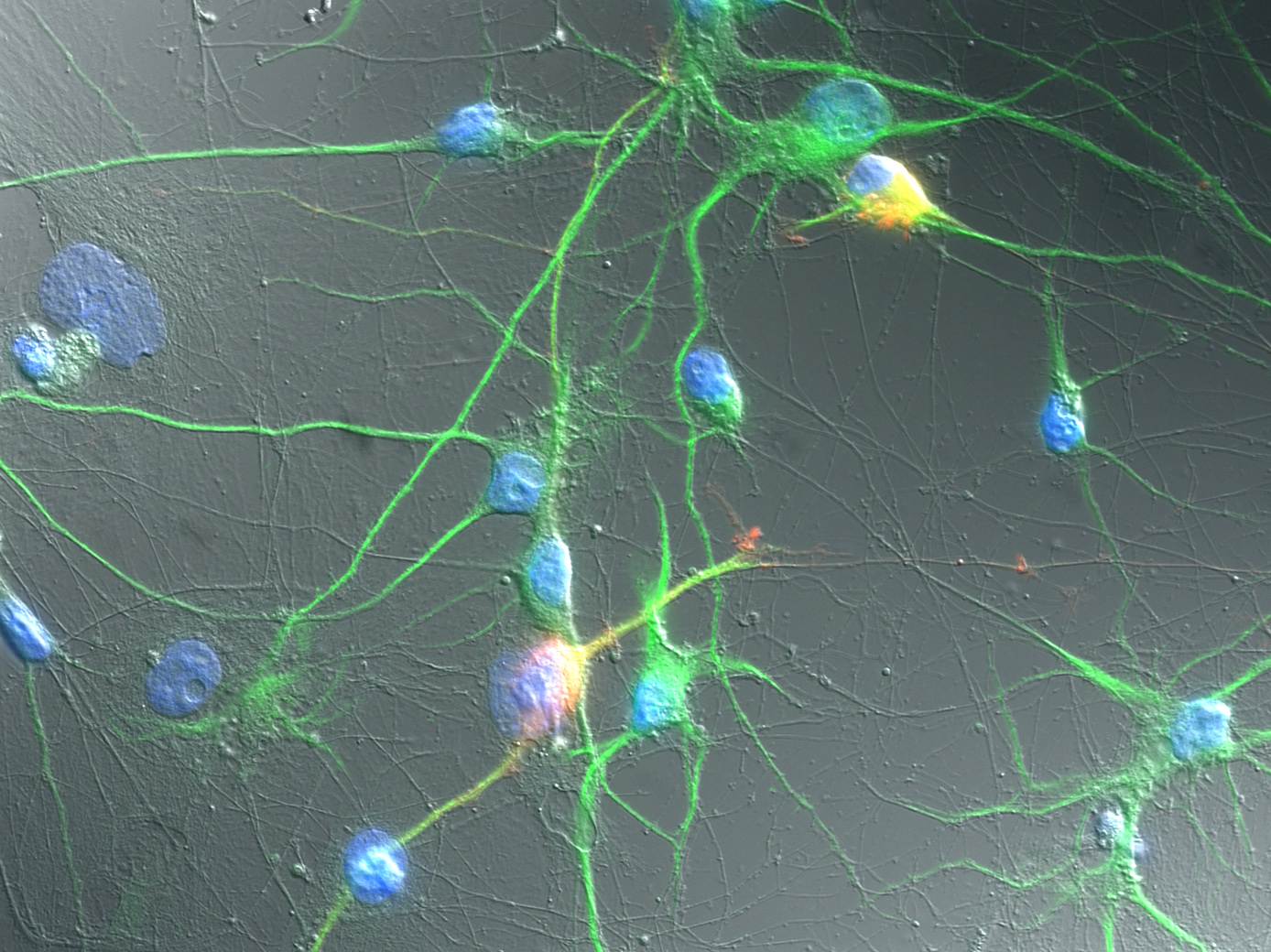

P.M.: We have around one hundred billion neurons in our brains. Each one communicates with around 10,000 others via junctions known as synapses. But there are also between five and ten times more glial cells. They were given this name at the end of the 19th century as they were thought to be the glue that held the neurons in place.

But over the past 25 to 30 years we have seen that these cells are much more dynamic than originally thought; this is one of the main areas of our research. They participate in the dialogue with the neurons and are essential for nourishing them, giving them energy and regulating transmission between them.

Behaviour and psyche are not down to neurons alone but also the dialogue between neurons and glial cells.

swissinfo.ch: Another surprising but reassuring discovery is that the brain is capable of building new cells even during old age…

P.M.: You cannot compare a brain to a computer which comes out of the factory with built-in circuits that remain the same for the rest of its life. Everyday experiences are constantly modifying our brain; this is known as plasticity.

Up until about ten years ago we were convinced that we were born with a set number of neurons and we lost them over our lifetime, which was a fairly depressing image.

We now know that certain regions of our brain can produce neurons from stem cells. But having new neurons is not the end of the story; they also have to be correctly linked up with the other neurons in the right circuits. This is an area that still needs to be explored.

swissinfo.ch: People say the brain is like a muscle and has to be used to be kept in good shape. How true is this?

P.M.: Absolutely. It’s very important if you want to age in a graceful and fulfilling way to keep your brain active and to be exposed to new things and new challenges like learning a language or instrument. Anything that stimulates your neurons and avoids routine is good. That probably stimulates neurogenesis, the production of new neurons.

Today we are starting to recognise the conditions that impede neurogenesis. One of these is chronic stress, which is well known for causing depression.

swissinfo.ch: Why do some people cope with stress better than others?

P.M.: Genetic studies are being carried out to try to identify people who are more resistant to certain kinds of stress or who perform better under stress. But we have to be careful with the results. What we might find is not an anti-stress gene but one or more genes that are present in a certain form and encourage better resistance.

But what is well known is that newborn babies subjected to major stress will show signs of hyperactivity as adolescents or adults. This is why you have to be as comforting and calm as possible with a young child if you want to offer them the best possible future.

“SYNAPSY – Synaptic Bases of Mental Diseases” is a long-term research project considered of vital strategic importance for Switzerland, one of 20 National Centres of Competence in Research (NCCR).

The project aims to discover the neurobiological mechanisms of mental and cognitive disorders, as one of the major challenges in psychiatry is to better understand how these illnesses originate. It is hoped that this research will lead to the development of improved diagnostic tools and therapeutic approaches.

The project focuses on the interface between preclinical research and clinical development, combining neuroscience with psychiatry. The research will help train a new generation of psychiatrists, who will possess both high clinical expertise and knowledge of the basic neurobiological aspects of mental functions and dysfunctions.

The institutions involved: the Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, Geneva University and Lausanne University.

The SFr17.5 million ($18.3 million) for the first four years of the project came from the Swiss National Science Foundation. The body last year approved around 2,900 research proposals with funding totalling SFr707 million – 6% up on 2008.

Pierre Magistretti is an internationally recognised neuroscientist who studied at Geneva University and completed his doctorate at the University of California at San Diego.

Since April 2008 he has been the director of the Brain Mind Institute at Lausanne’s Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL). He is also the director of the Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience, at Lausanne University.

He is also the co-author of several books with psychoanalyst François Ansermet from Geneva University, aimed at bridging the gap between neurosciences and psychoanalysis.

(translated from French by Simon Bradley)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.