Swiss Innovation Park to compete with world’s best

A new multi-site innovation park has Switzerland hoping that fostering closer ties between scientific research and business will help it maintain its position as a world leader in innovation.

Located in Villigen, canton Aargau, the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) is perhaps the least well-known of Switzerland’s scientific research institutes. However, on the global stage, it has a prestige akin to that of the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology in Lausanne and Zurich.

“Switzerland occupies an exceptional position,” explains PSI director Joël Mesot. “Seven or eight of our universities are ranked in the world’s top 20, which means that 70 to 80 per cent of Swiss students are educated in the best universities in the world.”

Innovation has become the latest buzz word for countries seeking to create new industries that help insulate their economies against increasingly turbulent global market conditions. However, many Swiss researchers are worried about the future. The acceptance of a popular initiative in February last year aimed at limiting immigration has reinforced the impetus for gathering forces to compete against other parts of the world.

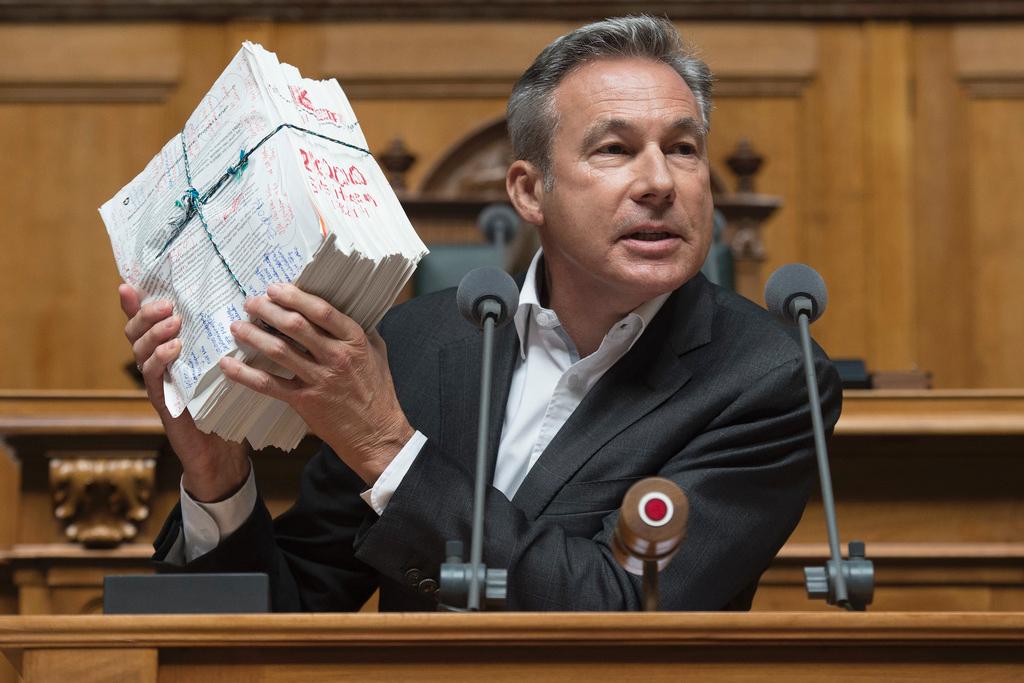

Well before the 2014 vote, several cantons launched a project called the “Swiss Innovation Park”, which has the support of the government under the auspices of the State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI).

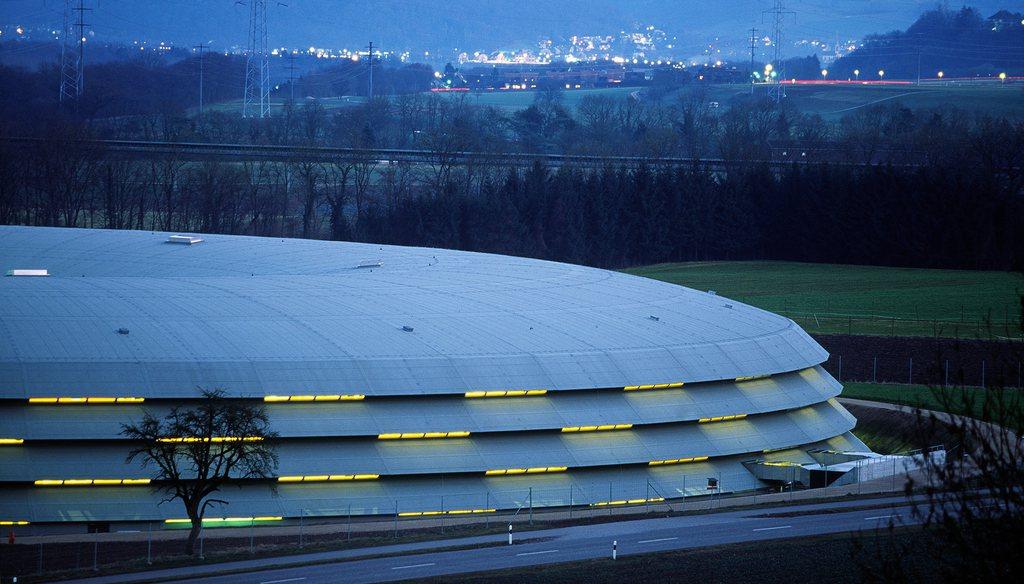

The Paul Scherrer Institute, which had already begun development on a project with canton Aargau, quickly entered the running to become a centre for the national project. In September, it became the first to launch its building, named the “innovAARE” park after the nearby river Aare.

The innovAARE park will prioritise four fields of research: particle acceleration technology, matter and materials, human health, and energy and the environment. The PSI, whose research was initially centred on nuclear energy, has focused on these fields since the 1990s.

A temporary, 400 square metre building is already home to two businesses that are hoping to benefit from the research opportunities offered by the PSI. The permanent buildings, which will comprise 19,000 square metres including laboratories, should be finished in 2018.

Five sites

The cantonal initiative will see five sites dedicated to innovation opened in a decentralised manner around Switzerland. Together, they will form the Swiss Innovation Park. The Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology in Lausanne and Zurich will become the two main sites.

The three secondary sites will be implanted in cantons Aargau, Basel Country, and Bern. The government plays a minor role in the project.

The Swiss Innovation Park is designed to guarantee and develop private investments in research and development. The five sites will make fully-equipped research space available that close to universities and existing businesses.

The Swiss parliament has allocated CHF350 million ($354 million) to the project, limited over a certain period of time.

‘Initiatives come from research’

There was, of course, much talk of innovation during the innovAARE inauguration. Thomas Held – sociologist, business consultant, essayist and former director of the liberal think tank Avenir Suisse – suggests that the concept had become a sort of consensus “miracle product” precisely because it is very vague.

“Classic economic promotion, such as tax breaks, has reached its limits and so everybody today is leaning towards innovation,” says Held. “The right, the left, employers, employees; you can’t be against it! The word is used almost as much as ‘sustainability’.”

“But for some, innovation means wind turbines, while for others it means nuclear reactors.”

Held thinks the PSI at Villigen brings together all the elements necessary to really foster innovation: talented researchers from all over the world, scientific infrastructure such as large measuring instruments not found elsewhere in the world, and fundamental research that is not oriented towards commercialising a product.

But won’t having such close ties to industry, if only for the construction of machines, affect the research’s independence?

“Absolutely not,” says Mesot. “The new presence of businesses in the innovation park in no way calls into question that independence.”

“The initiatives always come from the research,” he points out. “Don’t forget that universities and industry worked together in the past to build infrastructure like railways, dams, bridges or tunnels. Those have contributed to the fact that Switzerland occupies the advanced place it does in terms of innovation and competitiveness.”

Availability of instruments

Mesot cites proton therapy – a precision treatment for cancer patients – as a good example.

“Over the years, two technologies existed side by side: ours, which scans tumours very precisely in three dimensions, and another, which originated in the United States,” he says. “Up until 2010, most of the new treatment centres used the competing technology. But then our researchers and doctors were able to demonstrate the efficacy of the PSI procedures. Since then, all the new centres use our technology. It took about 15 years. Only fundamental research can bring about such a result.”

One of the two businesses which have already taken up residence in the innovation park, leadXpro, is active in medical research and interested in using membrane proteins to develop drugs. The other, Advanced Accelerator Technologies, is focused on commercialising the know-how developed by the PSI.

This know-how, to a great extent, comes from the Synchroton SLS (Swiss Light Source). The electron particle accelerator, which produces x-rays for the detailed analysis of matter, was inaugurated in 2001. This machine and other large measuring instruments are available to any researcher whose request is accepted – there is no privilege for in-house researchers, who must also submit a formal request.

Geographic proximity

In 2014, two-thirds of 1,328 such requests were accepted. Despite the fact that the number of synchrotons around the world has exploded, Mesot says the number of requests to use the PSI’s machine has not diminished.

“Despite the digitalisation and the modern technological possibilities, I believe that the geographic proximity between academic and industrial research is an important success factor for innovation,” Mesot said during the inauguration. “The innovAARE Park will encourage and support these meetings.”

The next “large instrument” of the PSI, the x-ray-free electron laser known as SwissFEL, is set to be inaugurated in 2016. With the help of this 740 metre-long subterranean machine, researchers will be able to observe extremely rapid processes like the formation of new molecules during chemical reactions.

The Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI)

The PSI is the largest research centre in Switzerland for the natural and engineering sciences. It was named after Swiss physicist Paul Scherrer (1890-1969).

It resulted from the fusion in 1988 of the Federal Institute of Reactor Research and the Swiss Institute for Nuclear Research.

The PSI has a number of large research tools, unique to Switzerland and the world:

- The Synchroton SLS (Swiss Light Source): Enables researchers to determine, almost to the nanoparticle, the detailed composition of very small structures.

- The spallation source SINQ: A state-of-the-art user facility for neutron scattering and imaging. Notably, it enables the study of new materials in the area of superconductors or computer memories.

- The Swiss Muon Source: The PSI has the world’s slowest muons. These particles enable researchers to determine magnetic fields inside materials.

- SwissFEL: The future x-ray-free electron laser will be operational in 2016.

The PSI has 1,900 employees, including 210 with doctoral degrees hailing from 42 countries. Another 150 post-doctoral researchers come from 40 countries.

Translated by Sophie Douez

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.