Pepper patent row heats up

What farmer wouldn’t want an insect-resistant pepper? Yet opposition is growing to a pepper patent granted to Swiss agrochemical giant Syngenta. A coalition has stepped up the fight against patents and the threat they pose to farmers everywhere.

“If we don’t defend our indigenous seeds, we won’t have any left and end up only growing standardised crops of multinational companies,” warns Cynthia Osorio, an organic coffee producer.

She travelled from Colombia to Zurich for an event on seed sovereignty, not long after three dozen agriculture, development and environmental organisations filed a complaint with the European Patent Office (EPO) over Syngenta’s patent on a white-fly-resistant pepper.

Osorio explained how international trade pacts and variety rights exercised by companies like Syngenta or Monsanto impact food sovereignty, diversity and livelihoods 9,000 kilometres away.

The Colombian farmer, who also works for the Red de Guardianes de Semillas de Vida (guardians of the seeds of life), argued that seed regulations and free trade agreements disrespected indigenous people’s rights and paved the way for patented crops to drive out local varieties.

“Our idea to preserve and restore diversity is not to keep seeds in a bank, but to spread them out among the people.”

Crop companies like Syngenta are not only criticised for some of their patents, but also for breeders’ rights. Companies and organisations with a vested interest in crops and seeds represented by lobby group CropLife International want to protect the rights on the products and technologies they invent.

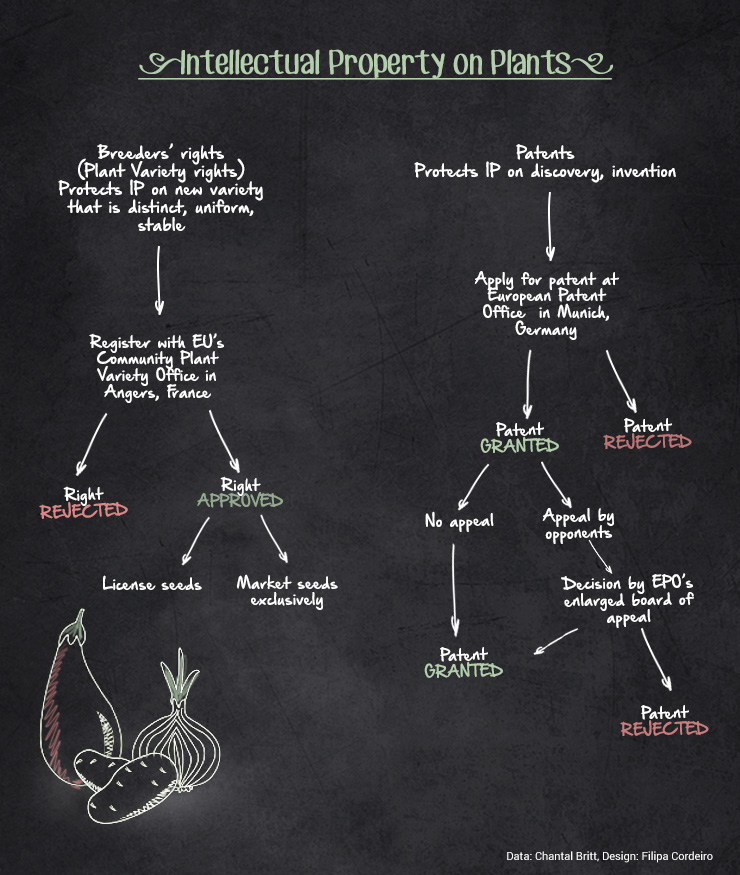

Patents and breeders’ rights grant them exclusive control over seeds and harvest and give them the option to sell exclusively the variety or licence to others. Syngenta argues that patents are an incentive for innovation. Inventions benefit growers and consumers, help farmers to increase productivity and may enable a lower use of chemical pesticides, it says. (See infobox)

The protection of intellectual property is a vital pre-requisite of value protection and value sharing. Patents play an important role in incentivising and accelerating innovation in agriculture so that farmers can increase productivity to sustainably address global food security.

The patent EP2140023 on a pepper trait provides better insect resistance than the wild type and meets the criteria of novelty, usefulness and inventive step. It covers the specific genetics and the technology used in its detection, while the original biomaterial remains free for use by other breeders. The innovation benefits growers and consumers and enables a lower use of chemical pesticides.

Syngenta gives breeders and researchers access to the pepper technology, as well as to some of its other plant-related innovations, through its e-licensing platform TraitAbility. All academic and non-profit organisations can make free use of the available vegetable native traits and enabling technologies for R&D purposes and can distribute the resulting products in developing countries free of charge.

Syngenta does not pursue patent protection for any plant biotechnology or seeds invention in any least developed country, defined as poor, economically vulnerable and weak in human resources, and subsistence farmers do not have to pay licence fees.

Syngenta employs more than 28,000 people in 90 countries and spent $1.4 billion (CHF 1.2 billion) on research and development in 2013.

(Source: Syngenta)

Opponents’ concern

What anti-patent campaigners – members of the coalition No Patents on Seeds – oppose are patents on processes that also cover the resulting products.

Monsanto claims patents on gene sequences or genetic variations in soy and maize, which cover plants inheriting the genetic elements, as well as their uses in food and feed. Syngenta, meanwhile, claims patents on crop yields, which cover the plants and their harvests.

They particularly reject patents based on conventional cross-breeding with wild varieties, which they consider discoveries and not proper inventions – as they say is the case with Syngenta’s patented resistance trait.

Although “essentially biological processes for the production of plants and animals” can’t be patented under the European Patent Convention, companies are accused of using a trick to claim rights on plants, seeds and food.

“One of the problems are so-called product-by-process patents, which allow the products to be patented, even if the process is far from being technical and innovative,” explains Eva Gelinsky, who works for ProSpecieRara, dedicated to the conservation of heirloom varieties and rare species.

For opponents, rights to living organisms are also unethical and go against the fundamental principles of most religions and cultures. They say that patents were created for machines and chemicals but not for life, and demand that humans, animals, plants, microorganisms and parts thereof should not be patentable.

“We need other protective systems, which respect ethical and socio-political boundaries and consider the interests of agriculture and research,” explained Fabio Leippert, responsible for development politics and food sovereignty at Swissaid, which is part of the No Patents on Seeds coalition.

“Patents particularly discriminate against farmers in developing countries where a large part of the biological diversity is found.”

For its part, Syngenta says it does not pursue patent protection for any plant biotechnology or seeds invention in any least developed country, nor do subsistence farmers have to pay licence fees.

Swissaid says that companies should not be given any incentive to take varieties from countries in the southern hemisphere as a basis for the patenting or to screen entire seed banks without reimbursing the countries for their genetic resources.

More

Understanding the patent process

Dependencies

The concern is not only about patents reducing diversity by blocking access to genetic resources and technology; they create dependencies for farmers, breeders and food producers.

Monsanto, DuPont and Syngenta together control more than half of the seeds traded worldwide, according to the European Civic Forum. While crop companies say that their products are addressing food security, protesters argue that the increasing dominance of a handful of companies endangers the lives of farmers in emerging economies because it poses a threat to their seed sovereignty and therefore to global food security.

Although Syngenta as an owner of intellectual property lets subsistence farmers use its seeds on their fields, non-subsistence farmers like Osorio must pay annual fees for registered seeds. They can’t afford them and want to freely use and exchange seeds. To illustrate that point, the event Osorio attended at Zurich’s alternative arts centre Rote Fabrik also hosted an informal “seed swap”.

Seed regulations demand that seeds may only be registered if they are distinct, uniform and stable, and in countries like Colombia farmers may only use these certified seeds. Indigenous crops never meet the criteria for registration, Osorio said.

Plant breeders’ rights, also known as plant variety rights, are granted to the breeder of a new plant variety, which is distinct, uniform and stable.

A plant patent is given to breeders who invent or discover a distinct new variety of plant. The inventor’s right excludes others from reproducing, selling or using that plant. Tuber-propagated or wild uncultivated plants are usually not patentable, and some nations, particularly developing countries, don’t allow plant patents.

In sub-Saharan Africa, seed companies can’t pursue patents. Plant breeders increasingly try to enforce their rights, but informal use – which makes up for 90% of the use – is difficult to restrict and control.

Although plant breeders’ rights should be kept separate from plant patents, there is an overlap and they are also not mutually exclusive. Exemptions from infringement on plant breeders’ rights, such as the saved seed exemption, do not create exemptions from infringement on the patents covering the same plants, and vice versa.

Crucial decision

Laws and international free trade agreements play directly into the hands of large multinational companies, which mass-produce monoculture seed varieties at the expense of diversity, explains Jürgen Holzapfel from the European Civic Forum and co-founder of the agricultural cooperative Longo Maï, which organised Osorio’s trip.

“The largest number of rice varieties for example are found in Asia, where farmers have been improving their properties and yields for centuries,” said François Meienberg from the non-governmental organisation Berne Declaration. “But it is not those countries claiming the rights on this work, but companies like Syngenta who have patented hundreds of genomes.”

The coalition’s appeals against several patents mean, however, that opponents have a foot in the door, so companies can enforce them until the EPO has made a decision on the legal interpretation of what is patentable, which is expected by the end of the year, Meienberg explained.

“If the enlarged board of appeal decides in our favour, it will become very difficult for Syngenta, and if Syngenta wins, then the political process will start,” Meienberg said. “But even if it should come to that, we expect politicians [to move in our direction] because many small and medium-sized plant breeders also oppose some patents claimed by multinationals.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.