Shifting freight traffic to rail proves daunting

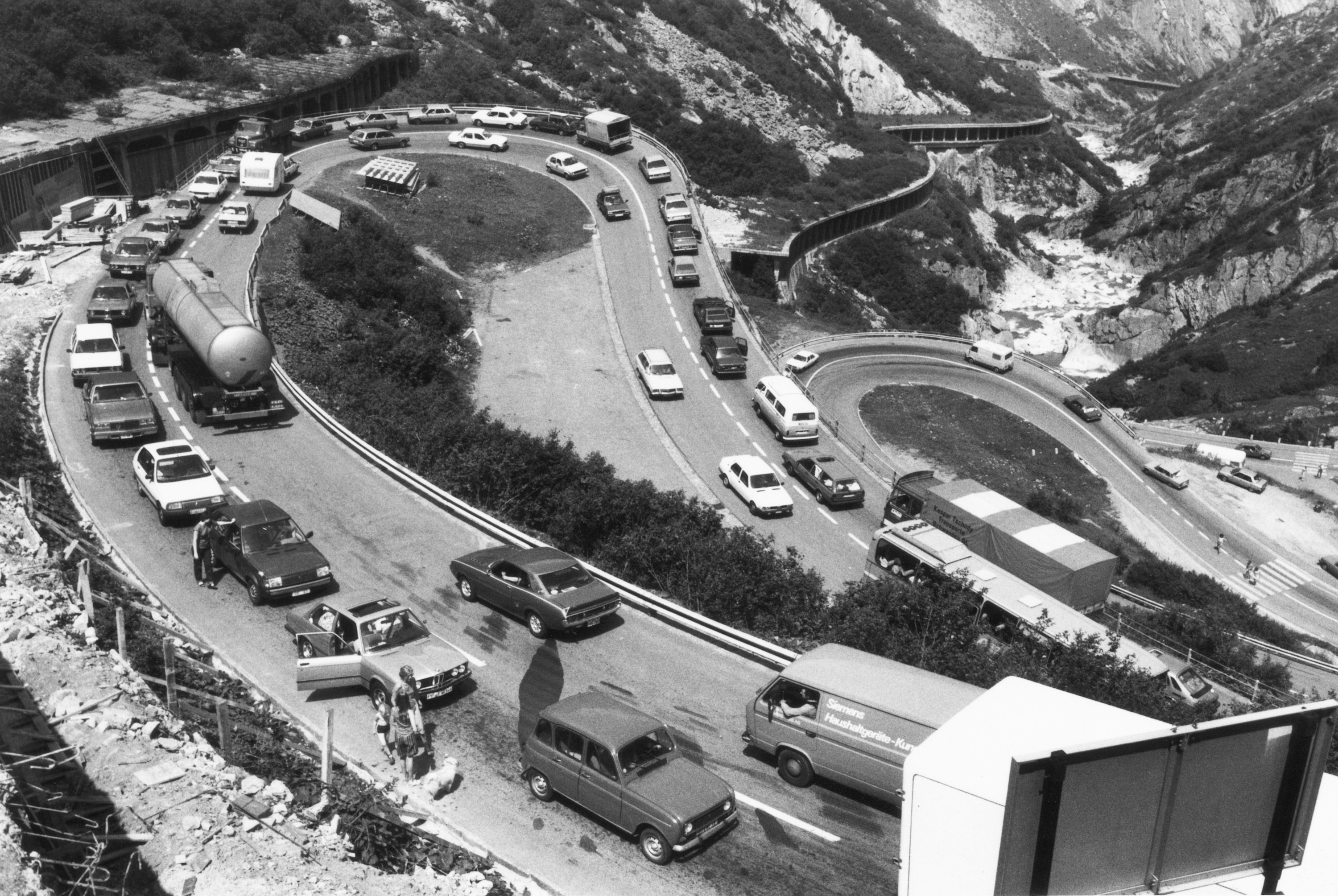

A goal of cutting down on heavy traffic crossing the Alps by boosting freight travel by rail has been enshrined in the Swiss constitution for nearly 20 years. But with roads still faster than rail, it is starting to look like an illusion.

Rail transport absorbs two-thirds of the freight traffic crossing the Alps every year. Despite the government’s efforts, its market share is not increasing, nor is likely to in the foreseeable future.

Swiss voters accepted the Alpine Initiative in 1994, sending a clear signal as to what future policy on transportation was to be. The resulting article 84 of the constitution stipulated that “transalpine traffic involving transportation of goods through Switzerland is to take place by railway”.

While the number of heavy trucks crossing the Swiss Alps has declined, from over 1.4 million in 2000 to 1.25 million in 2010 (three-quarters of which go by the Gotthard axis), the proportion of freight conveyed by rail has also fallen – despite the subsidies paid to make it more attractive.

In 1999 rail freight traffic was 68.7 per cent (compared with 31.3 per cent by road), while in 2010 it was 62.6 per cent (37.4 per cent), according to Alpifret figures in the 2010 report on monitoring of road and rail freight transport in the Alpine region.

Last December, approving the report on the transfer of traffic for 2011, the government admitted that “the instruments currently available [for shifting traffic from road to rail] will not be sufficient for achieving the objective of 650,000 trips annually set for 2018”. The opening of the Gotthard base railway tunnel, scheduled for 2016, will not change the situation in any substantial way.

“For over ten years now we have been doing all we can. But the limits of the transfer policy are becoming more and more apparent,” said Rico Maggi, a transportation expert and the director of the Institute for Economic Research at the University of Lugano

Switzerland ahead of the rest

The glass can of course been seen as half full. Without the additional incentives (see sidebar) to support the transfer of traffic, the number of trucks would certainly be greater – by at least 600,000 per year, according to the Federal Transport Office.

At the European level, on the other hand, Switzerland is an exception.

In France, the truck continues to rule the road, and the railway seems to be running out of steam: whereas in 1999 rail accounted for 19.9 per cent of goods tonnage transported through the Alps, in 2010 the proportion dropped to 10.5 per cent. Only very recently, in 2009, has the government put forward an initiative to transfer at least 500,000 trucks a year to rail by 2020 and increase the proportion to 25 per cent.

In Austria the proportion is higher and rail transport is growing, but it still conveys only a third of the goods.

Timing

The problem of rail transportation is not really one of price. If you take to the highway, costs along the Cologne-Busto Arsizio corridor (820km) reach €1.85 per kilometre per vehicle, according to data provided by Alpifret. Opting for combined transport, the same stretch costs €1.71/km, without taking the subsidies into account.

Combined road-rail transport is thus quite competitive. The obstacles are of a different kind.

“The transfer policy is based on the idea that flows of traffic can be regulated like flows of water,” said Maggi.

“In reality, however, companies have to decide individually how to produce and transport their goods. There are many small and medium-sized companies that cannot work with a rather inflexible logistical system that is not conceived for short-term needs. And on the other hand, there are goods that are not suitable for rail transport.”

In spite of traffic jams and problems of various sorts, the highway remains the fastest way to get from point A to point B: 11 and a half hours from Cologne to Busto Arsizio, without holdups, compared to about 22 hours by train.

“The potential for transfer is fairly slight,” concluded Maggi.

No turning back

Despite the rather middling results achieved so far, the Swiss government and parliament intend to continue on the path they have set out for themselves.

On June 12, the House of Representatives adopted a motion containing a series of proposals to encourage transport by rail.

Some of these measures are currently under review. The government will soon present its proposal to build a corridor on the Gotthard axis permitting transport of four-metre-high semi-trailers (currently it’s 3.80 metres), which would mean an increase in capacity. They are also considering the possibility of enlarging the loading terminals in Italy.

For the government these provisions will encourage “a lasting transfer of heavy transalpine traffic from road to rail”. Yet the real impact is expected to be modest.

To reach significant results, “much higher” taxes than the current ones for heavy trucks on the highway would be required. The margin of manoeuvre is limited, though. Currently a truck making the crossing from Basel to Chiasso pays about SFr290 kilometre-based tax on heavy goods vehicles. The tax could be increased to SFr325. Anything higher would not be in conformity with the land transport agreement concluded with the European Union.

Another strategy advocated for some time now is the creation of an Alpine Crossing Exchange (see sidebar). A convention introducing an international system to manage traffic appeals to the Swiss government, but not to the other parties involved.

“Given the lack of political consensus found in neighbouring countries of the European Union” the establishment of an Alpine Crossing Exchange in the next few years “seems unlikely”, says the government.

For the transfer of traffic, then, they will continue to proceed by small steps. Nothing revolutionary is on the horizon.

The aim of the traffic transfer policy is to protect the Alps from the negative effects of through traffic.

The legislation fixes at 650,000 the maximum annual number of trucks allowed to be in transit across the Swiss Alps two years after the opening of the Gotthard base tunnel railway, that is in 2018.

In December 2011, however, the government made clear that, under current conditions, this aim will not be reached. In 2010 about 1.25 million trucks transited on Swiss alpine routes.

In Switzerland the situation is better compared with other countries of the alpine region, because the railway absorbs about two-thirds of the goods traffic through the Alps. In Austria the proportion is one-third, while in France it is less than one-tenth.

To try to shift freight traffic to rail, various additional measures have been introduced which aim to equalise competition between rail and road, increase railway productivity and improve the flow of traffic on the roads.

The measures include operating subsidies for combined traffic and railway freight traffic, investment in terminals and financial aid for feeder tracks. In 2011 SFr234 million were budgeted for these three items.

Another important instrument is the kilometre-based tax on heavy goods vehicles, applied to road transport. In 2011, this tax yielded SFr1.5 billion for the federal coffers. A third of this amount is earmarked for the cantons, which use it mainly to finance the costs of road traffic. The federal share is used mainly in public transport projects.

The Alpine Crossing Exchange is a proposed instrument based on market mechanisms, the purpose of which is to encourage the transfer of freight traffic from road to rail.

In practice this would mean that a maximum number of heavy vehicles in transit through the Alps is fixed annually, and these transit credits are sold to the highest bidder.

The credits would apply to all the alpine passes in the country, while it would be left up to the transporters to choose their own route.

To avoid just diverting the traffic through neighbouring countries, the Alpine Crossing Exchange would require the establishment of a coordinated approach within the entire alpine region.

(Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.