When Zurich’s New Left rode the pop culture revolution

1968 was not a revolution that came suddenly from nowhere, but represents a wide range of social upheavals. Here we examine the role of the New Left, and how it tried to harness the youth fervour of the time for pop culture.

In 1967, the landlord of the Café Odeon in Zurich threw a young woman out because she was wearing a miniskirt. Days later, a crowd of people carrying banners demonstrated loudly for the acceptance of miniskirts. Demonstrations for miniskirts had already taken place in London in 1966, when fashion label Dior planned to remove them from its range. The miniskirt had become a symbol for the explosive changes taking place in the world in the 1960s, and it seemed that at last something revolutionary was happening again at the Odeon, the place where Lenin used to read the newspapers.

The fashion problem was discussed fervently at political meetings of the Youth Wing of the Communist Party. The pro-miniskirt demonstration showed that the youth could be mobilised for political protests, according to one person at the meeting. In the era of pop and beat, this kind of trivia could also play an important role in political activities, he said. It was just a question of trying to bring the people who had taken part in this demonstration “onto a higher level”. Concretely, miniskirt and pop fans should be turned into useful revolutionaries.

New revolutionaries

The Communist Party Youth Wing in Zurich was not a big group. On good days, it comprised two or three dozen people and it only existed from 1964 to 1969. But the short history of this faction of the party illustrates the history of the left in the 1960s – the rejection of old socialist ideas of party leadership, a farewell to the proletariat, and the search for new revolutionaries. Such generational conflicts between the “old” and “new” left reached a peak at that time in the US and in Europe.

The Communist Party had an ageing membership in the early 1960s and the years of isolation after the Hungarian Uprising had taken their toll on the left. The founding of a Youth Wing in 1964 was welcome. Most of the new party members had become politically active in the context of the first Easter marches against nuclear weapons at the beginning of the 1960s. The “nuclear youth” was so often pushed into the radical left corner that it eventually set up home there. They wanted to present themselves as unambiguous opponents of the mass media and the governing parties, in other words of the “system”.

Generational rift

But the alliance between the young and older members of the Communist Party didn’t work for long. Even among radical left-wingers, a rift emerged between the generations in the 1960s. The old guard was no longer willing to put up with “youthful impatience and arrogance” and in 1969, the youth wing was dissolved across Switzerland.

Why did it come to such an abrupt end? After the era of Stalin and the Soviet invasion of Hungary, dissidents in the east and socialists in the west started seeking new forms of socialism. Many of the people that critics in 1968 wanted to send to Moscow because of their convictions would have been sent back immediately for the same reason.

The differences were deep: theoreticians of the New Left no longer saw factories as the main instrument of oppression, but instead focused on the mass media. The struggle, as the Communist Party Youth Wing in Zurich wrote in its founding manifesto, must be targeted at the “intellectual and cultural (ideological) level”. It was no longer the economic needs but the “intellectual existential crisis of the working Swiss today” that should be the focus. The struggle for material needs seemed a lower priority in the economic boom of the 1960s.

In the run-up to 1968, left-wing criticism became cultural criticism. Only after the intellectual and cultural crisis was overcome could the parameters shift.

Who will lead the revolution?

There was much discord on the question of who should provide the impetus for this shift. Older left-wingers believed it should be the proletariat, or the working classes, while members of the New Left – including the Youth Wing of the Communist Party – believed it was no longer the workers but the radical youth, led by protesting students, who would bring the revolution.

They were guided by theoreticians like Herbert Marcuse who invested their hopes in groups marginalised by society to provide the political momentum for change, hopes that had previously focused on the working classes. Enthusiasm for the miniskirt demonstration and pop-fans was therefore the product of new Marxist theory.

To stoke the fervour of this new clientele, alternative political means were necessary. Activists favoured small protests aimed at producing a big media sensation. The Zurich Youth Wing of the Communist Party called for protests to be “more interesting, more extraordinary, more radical, more humorous!”

Its mother party was rather irritated, as the Youth Wing member Franz Rueb recalled in writing. “The guys and girls in the Youth Wing of the party skipped through the streets and squares distributing funky pamphlets of which they were immensely proud, organised teach-ins and sit-ins, and formed gangs to storm public squares by the dozen in protest at the police, the legal system or repressive education. And they did all this without their party’s blessing. Older comrades shook their grey heads in disgust.”

These protests multiplied in the spring of 1968. After the murder of Martin Luther King, people took to the streets of Zurich and a little later, demonstrators burned a Vietcong doll in front of the headquarters of Dow Chemical Company, the main producer of napalm. At the end of May, demonstrators disrupted the traditional torchlight procession by students at the University of Zurich. The Communist Party’s Youth Wing had by now merged with other New-Left groups to become the group of Progressive Workers, Students and Pupils (FASS).

Riot in Zurich

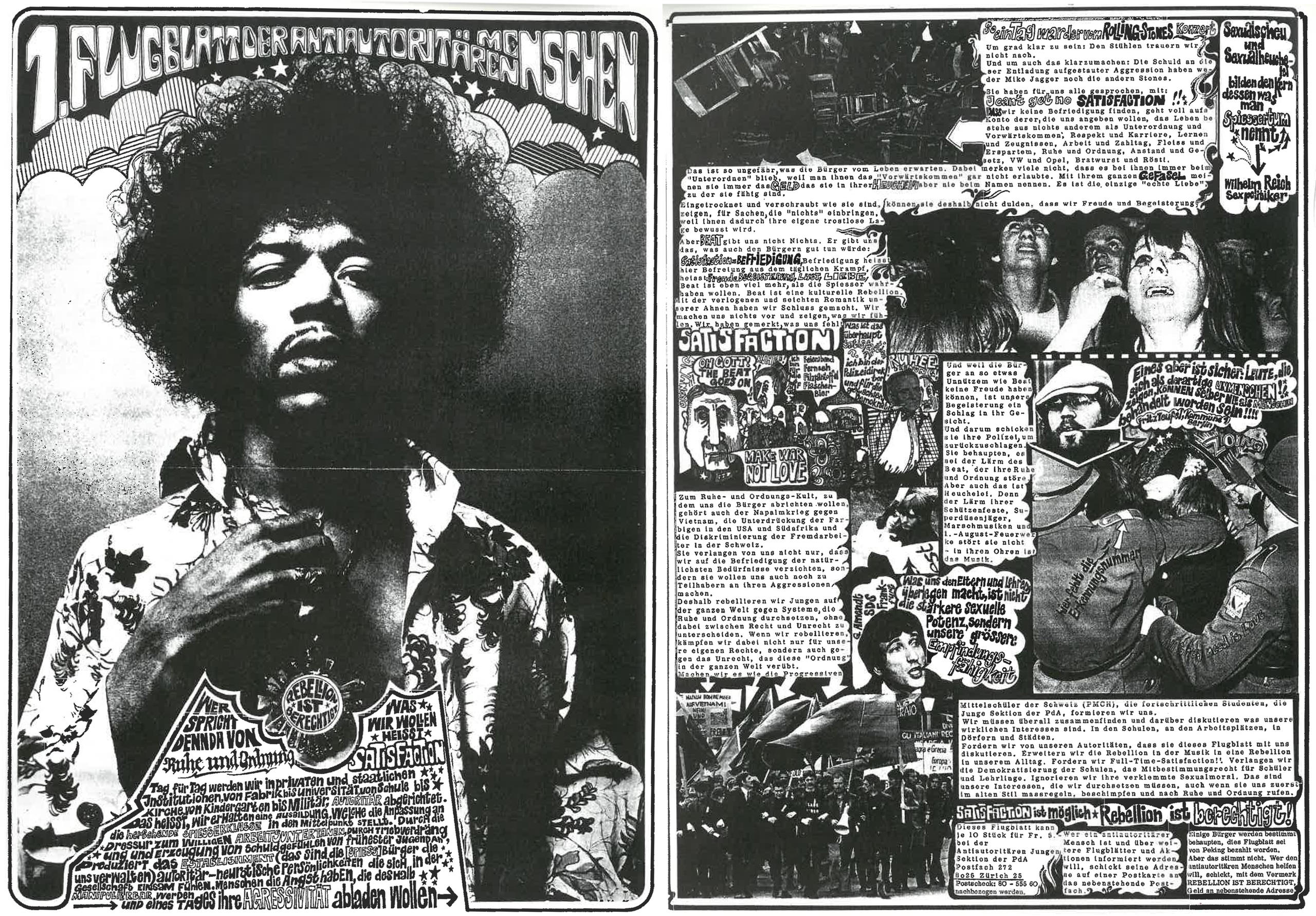

At the end of May 1968, Jimi Hendrix played at the Hallenstadion stadium in Zurich. The police were ready with dogs, and after the concert, loiterers were chased out by force. During the concert, the FASS distributed a long-planned pamphlet. Theory and practice aligned – a revolutionary pamphlet was distributed to dancing youths from the stage. In the middle of the pamphlet there was a portrait of Hendrix. It could also be hung up as a poster. The text, however, was aimed at turning a passion for music into revolutionary fervour:

“Beat is a cultural revolution… The fact that we get no satisfaction is entirely to blame on those who want to tell us life consists of nothing but submission and personal advancement, respect and career, learning and grades, work and pay-day, diligence and savings, peace and order, law and decency…”

The Communist Party Youth Wing took full blame for the riot that followed the concert. The “Zürcher Woche” wrote in outrage: “You don’t distribute a pamphlet like that to 10,000 youths, nourish them for hours with beat, pop and yelling and then sit back comfortably to watch what develops. This is how the Youth Wing of the Communist Party, which is part of the anti-authoritarian youth, is manipulating an uprising.”

By now, France was in chaos. May 1968 had expanded the realm of the possible. The conservative press feared anarchy. At the end of June, Zurich entered the ranks of cities in revolt. Not surprisingly, it was over the struggle for an autonomous youth centre, which would be a free space for both politics and music.

Translated from German by Catherine Hickley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.