One man’s 19th-century journey to Australia – rediscovered

Piecing together the story of her great-grandfather, who emigrated to Australia from Switzerland, Barbara Mullen also uncovered the prejudices non-English settlers faced. She believes the exploration of the social and cultural changes that have taken place in her family over the generations can provide valuable insight into understanding the way things are today.

My great-grandfather Alessandro Mattei was 16 when he joined the younger men of Cevio and one adventurous woman, who were walking out of the valley. It was towards the end of summer in 1855 and they were travelling to Hamburg to board ship for the gold fields of Australia. This was an act of desperate hope. They left behind the women, the older men and the children. They left behind famine and political instability and upheaval. They were travelling towards a new world of promise, a golden future.

The ship owners of Hamburg had travelled earlier through the desperate valley whipping up a frenzy of gold fever: a promise of wealth and a solution to their problems. The villagers scraped together money to pay their fares, and like all refugees they intended to return home soon. When they boarded the boats, they had the first inkling that maybe this journey would not be what they had expected: conditions were more cramped than they had been led to believe and their ebullient optimism was dampened a little.

The above background to my great-grandfather’s story was eye-opening for me when I discovered on this very website the special reports on historic migrations from Italian-speaking Switzerland. I had found the answer to the important question of why Alessandro came to Australia, and I began to understand why he never returned to Cevio. This was in 2010, but the story of the research of my great-grandfather’s life had begun decades earlier.

The first phase of my quest began when my mother gave me Alessandro Mattei’s name and place of birth along with other family names. Then I began researching seriously, and in 1992 found out what I could of Alessandro and the Mattei family in Australia based on the microfiche records I was able to source.

The following year I travelled to Switzerland, where I spent many hours looking up the family records in the local church in Cevio. l found much information which I recorded and photographed. The priest, however, was extremely protective of the privacy of anyone not directly related to me. The Civic Registry in Cevio was most helpful and there I found some information which l was allowed to photocopy.

It wasn’t until 2010 that I resumed my investigation with a strong sense of commitment. The journey has been a roller coaster ride ever since.

I started researching the reasons for my family’s migration and soon I discovered that what I was studying was a massive relocation of historical significance. I had met Giorgio Cheda in 1993, but it was in late 2010 that I studied his book L’emigrazione ticinese in Australia – which wasn’t that easy to do, given that it is written in ltalian!

I also began to piece together more family information on cousins, aunts and uncles who migrated to Australia. ln doing this I was aided by Joseph Gentilli’s book The Settlement of Swiss Ticino lmmigrants in Australia and Clare Gervasoni’s Research Directory & Bibliography of Swiss and ltalian Pioneers in Australasia.

At this stage I had made contact with cousins who had also been researching the family tree. By then I had gathered most of the data available from the internet (no need for microfiche anymore!), as well as lots of information of an historical nature about the Ticinese migration and the family in Cevio. Subsequently I read Bridget Carlson’s doctoral thesis, lmmigrant Placemaking in Colonial Australia: The ltalian-speaking Settlers of Daylesford.

I gradually began to understand that Alessandro Mattei, when he decided to stay in Australia, had the idea of continuing with the village way of life of Cevio but in an Australian setting. He wanted to create a family in Australia to be proud of just as the Matteis in Cevio had a family to be proud of, a family that would be well respected and of standing within their community. lt dawned on me that Alessandro had consciously set about building a family; in doing so he was following a time-honoured blueprint, while adapting it to new circumstances.

My cousins and I began to delve deeper into the available records.

Alessandro Mattei landed at Melbourne in September 1855. Ten years later, in November 1865, he appears to have married Catherine Mulcahy. No record of the marriage has been found yet: no civil record, no church record. lt is highly unlikely however that they didn’t marry. They had 12 children who all survived to adulthood – a very remarkable achievement at the time, especially given that this was not a family with money.

We traced the whereabouts of the couple and Alessandro’s occupations through the birth records of their children. They met in the Daylesford area where Alessandro had been engaged in various types of work, including gold digging at Champagne Gully. Then they moved to Monkey Gully near Smythesdale, a two-day horse ride away, where their first child was born in 1868. Here Alessandro began his work as a woodsplitter.

Over the next 20 years they lived in at least eight different places within the State Forest in the Shire of Ballan, where Alessandro continued to work with timber, sometimes as a labourer in a timber mill, sometimes contracting as a splitter. Baptism certificates gave us information on the godparents for the children, including Alessandro’s brother Pietro Mattei, who had returned to Cevio and had come back to Australia for the baptism, perhaps before he left for California.

All the while, the question at the back of our minds was: what was Alessandro experiencing, what was he thinking?

When Alessandro arrived in Australia as a 17-year-old, he had experienced a traumatic journey by ship; he was then exposed to violence in the gold fields when, only a few weeks after his arrival, a member of his extended family murdered another member at Blackwood.

The gold fields were rough and ready places. Within three months of his arrival, a violent fight – “a battle” in the words of contemporary accounts – took place between the English and the ltalians at Daylesford. In a letter home, G. Respini, a family friend of the Matteis, described how the English were afraid of the Swiss ltalians’ knives.

ln 1859, when Alessandro’s brother Pietro applied to the court for a refreshment licence for a tent at Stony Creek, it was claimed that “[r]ows might take place, and ltalians were not like Englishmen, but used knives, and the government had sent special instructions regarding these applications from ltalians”.

The licence was granted hurriedly to stop the lawyer representing Pietro from talking about recent events in which ltalians were unfairly charged.

Alessandro further experienced the difficulties of not speaking English in an English-speaking environment, and the disadvantage of not being British and therefore lacking the same rights to own land.

The peaceful communal life of Cevio had been replaced by an uncertain context in which one had to vigorously assert oneself and one’s rights. One day at the State Library my co-researcher cousin and I were reading the Daylesford newspaper of 1868. At the time, the non-English in the area outnumbered the English but the paper only reported on events relevant to those of English background. The only Swiss Italian reference was an advertisement for a local hotel owned by a Swiss ltalian. We left the library early; I was angry over the exclusion by omission of my people. ln our research we had come across incidents of prejudice reported openly in the paper, but this was the first time I recognised that the community life of my people was not seen as relevant.

Nothing is ever linear in this research. At one stage, I decided I needed to build a better picture of Alessandro Mattei’s family: I believed I had all his brothers and sisters but I was lacking information about his extended family. Alessandro was 16 when he left his village; further, there were already many men from the village here in Australia, including his brother Pietro, so I knew he had to be with family. I had the names of the people he had travelled with and lived with, but was unsure how they were related. I decided I would try to identify his uncles by marriage. I ordered the film of the church records in Cevio from the Library of the Church of Latter Day Saints. With greater freedom to explore other Matteis than I had when in Cevio, I was able to identify another aunt and the husbands of all the aunts. This was very helpful as it put Alessandro in the company of his family members out here and identified many cousins too.

I also found out that Alessandro’s uncle Pietro was indeed the important doctor who documented the story of the famine in Cevio and the consequences of the loss of the men to the village. I began to reread Cheda’s book with this new information and this led to the discovery that Alessandro’s grandfather himself was also a doctor.

Alessandro and the family later moved to Green Hills near Blackwood, where they experienced a few golden years before the depression of the 1890s and his own gold lust caught up with him. That last sentence alone required extensive research into wills and probate records, newspapers (now fully searchable through the National Library of Australia’s search engine Trove), school records, local Italian Historical Society history books, field visits and more.

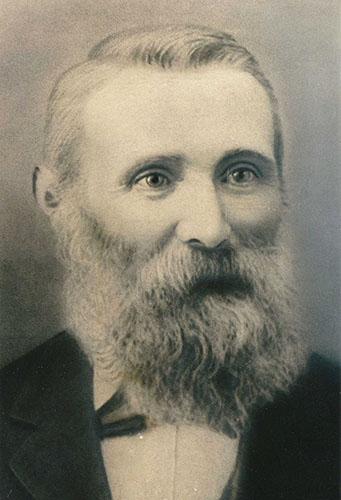

In the family there is an important photo of Alessandro and Catherine with some of their children and their first grandchildren. It is known as the Rovana photo, Rovana being the name they tellingly gave to their house in Green Hills. lt was the first and only house the couple owned. When we visited Rovana in 2011, the chestnut trees that would have been there in that time were still thriving.

Chestnuts were important in Cevio: the people used to grind them and use their flour to make bread or polenta when wheat or corn was not available.

At the turn of the century, Alessandro and Catherine, now in their late fifties, left Green Hills with the children who had not yet married and started out again at Toolangi, near Castella, in the Murrumdindi Forest. Here the family worked hard to establish itself, the sons taking up the heavier timber work. The couple wanted to see all their children well married and provided with a foothold on which to build and create their own families.

Alessandro Mattei died on July 7, 1905. He had been sick for the last three months with chronic bronchitis and dilation of the heart. He was 67. When he died, his family had begun to spread throughout Victoria; a core of six of his children, however, remained in Toolangi, where they maintained the idea of a family home.

It is questionable how successful Alessandro was in fulfilling his desire of establishing a strong family name, a family that could be proud of its heritage and its social standing. Toolangi was a lifetime and a world away from Cevio, and family life such as it was in Cevio in 1850 was not possible for the Matteis of Australia.

By the Second World War, no one was left at Toolangi.

In its small way, the journey that this family experienced mirrors the journey of this research – full of ups and downs: drama, success, loss and frustration.

Originally published in the Italian Historical SocietyExternal link Journal, Melbourne

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.