Becoming a mom after age 50: two viewpoints

Around 30 women over 50 gave birth in Switzerland last year. In fact, there were even three newborns whose mothers had already celebrated their 60th birthday. Doctors have expressed concern over this trend.

With 32 being the average age for giving birth in Switzerland, the case of advancing maternal age is leading to debate. Is criticism justified? And should lawmakers intervene? Opinions differ in the editorial offices of swissinfo.ch as well.

No, criticism is not justified, says Larissa M. Bieler, editor-in-chief of swissinfo.ch

The incredulity is strong, the outcry as well. Women who become pregnant late in life face significant criticism, attacks by the public and the media. They should be ashamed of themselves. But why?

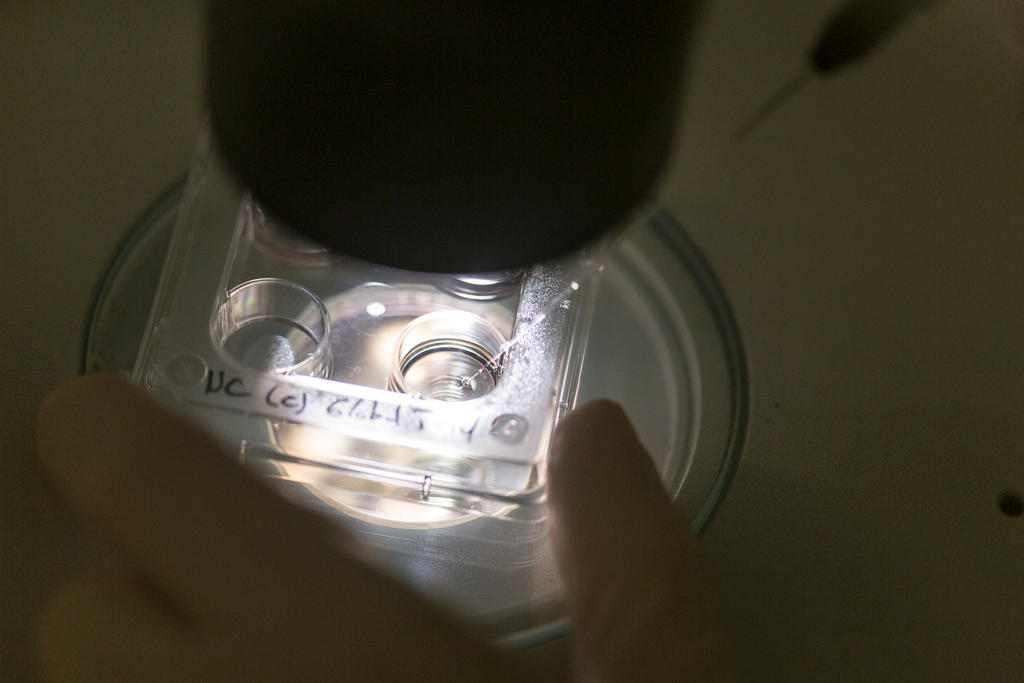

Medically, a pregnancy that results from fertilisation of the eggs of a young donor is largely independent of the age of the woman carrying the child. According to reports in the media, the oldest Swiss woman to give birth was 66. She delivered twins conceived using donated egg cells and semen. The oldest Spanish woman was a week shy of her 67th birthday, but died two years later of cancer.

And out comes the pseudo-moral sword that people swing whenever society is overwhelmed and doesn’t know to react toward an individual who takes advantage of her freedom to choose, and who chooses to reward her own desires.

Should we be able to exploit our freedoms whenever we want to? Should self-determination be the ultimate goal of our society?

The issue of the freedom of the individual raises serious ethical and psychological questions. Similar questions are at the heart of debates over other current issues. Assisted suicide, for example. Or the adoption of children by same-sex couples. Or the sterilisation of disabled people. Or, as in this case, late pregnancy. On the one side we have what is “medically possible” and on the other what is considered “ethically responsible”. But – and this is the salient point – there are no norms for deciding what is ethically responsible.

Should a woman be able to decide for herself, if her decision also affects a helpless child who is dependent on her? Such mothers are accused of being selfish and irresponsible.

But the argument of what is “for the good of the child” muddies the debate. “For the good of the child” cannot be defined. Is a 20-year-old a better mother than a 60-year-old? Are lesbians better mothers than heterosexuals?

Ethical responsibility is something else. It is a responsibility you have to yourself, to make a carefully weighed, well-informed, and conscious decision. Women today are much more independent. Their lives are less affected by prevailing prejudices, clichés and society’s expectations. In the old days, having a child was not a choice. Today, women are separating themselves from restrictive imperatives and social norms – and are using their bodies the way they want to.

And that’s the way it should be.

Yes, criticism is justified, says Reto Gysi von Wartburg, assistant editor-in-chief of swissinfo.ch

The personal freedom to have children when you want is a valuable asset. And naturally there are circumstances that speak for waiting until well into the second half of life to start a family: a major career opportunity presents itself, it takes a while to find the right partner, or the desire to have a child develops over time.

But still: the good of the child should be the prevailing consideration. A child has the right to parents – ideally, to parents who are ready for the responsibility and who have at least a little of the energy needed to keep up with their offspring. Parents who are over 50 at the birth of their child will be retiring before their son or daughter even gets out of school.

The probability that a child born to over-50 parents will celebrate his 20th birthday without them is more than five times higher than for a child whose parents were in their 30’s when he was born.

Being orphaned at an early age is not the only danger. The risk of having parents who are seriously ill or in need of nursing care while the child is still young is significantly higher as well. In any case it’s clear that children with old parents will have less chance of a “carefree” youth, and may also miss out on the opportunity to get to know their grandparents.

Personal responsibility and careful weighing of the risks are more important than regulation in this case. Physically, men retain the option of becoming parents at a greater age than even before, and women can go to nearby countries to find legal options to satisfy their desire for motherhood.

In fact, legislators have already thought about how old parents should be: according to Swiss laws on adoption, the difference in age between an adult and a child being adopted can be no greater than 45 years unless there is a pre-existing relationship between the two.

Translated from German by Jeannie Wurz

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.