Swiss develop rapid infrared cocaine test

Researchers at Zurich’s Federal Institute of Technology (ETHZ) have helped create an infrared device that can detect tiny traces of cocaine in human saliva.

The compact detector, which was created as part of a national new technology research programme, Nano-Tera, may be adopted by law enforcement agencies to test suspect drivers.

“Current rapid tests conducted by the police in the streets do not give the concentration of drugs consumed, just negative or preliminary positive results, which are sometimes wrong and not recognised by the courts,” ETHZ physics professor Markus Sigrist told swissinfo.ch.

“It takes time to take a suspect to hospital to given them a blood test. So obtaining a quantitative concentration in saliva samples would be a major step forwards.”

Sigrist heads a group of ETHZ scientists working on the development of an optical sensor to measure cocaine concentrations. It is one of nine research teams from five Swiss scientific institutions, including ETHZ’s sister institute in Lausanne and Neuchâtel University, working on the four-year project.

Using the properties of infrared light and a detector created by Neuchâtel University, it took Sigrist’s group three years to determine the precise wavelengths of cocaine when absorbed in saliva, as well as other substances.

“We have been able to determine all the different possibilities: alcohol, caffeine, solvents and painkillers,” he added.

The Zurich professor believes it is possible to detect cocaine levels as low as twenty nanogrammes per millilitre of liquid using the technique. If someone smokes cocaine, up to 500 micrograms per millilitre are still present in the saliva for a short time.

“Based on what we’ve obtained so far we need one year to refine the nanogramme per millilitre results, and another three years to create a suitable platform so an industrial partner can then market the product,” said Sigrist.

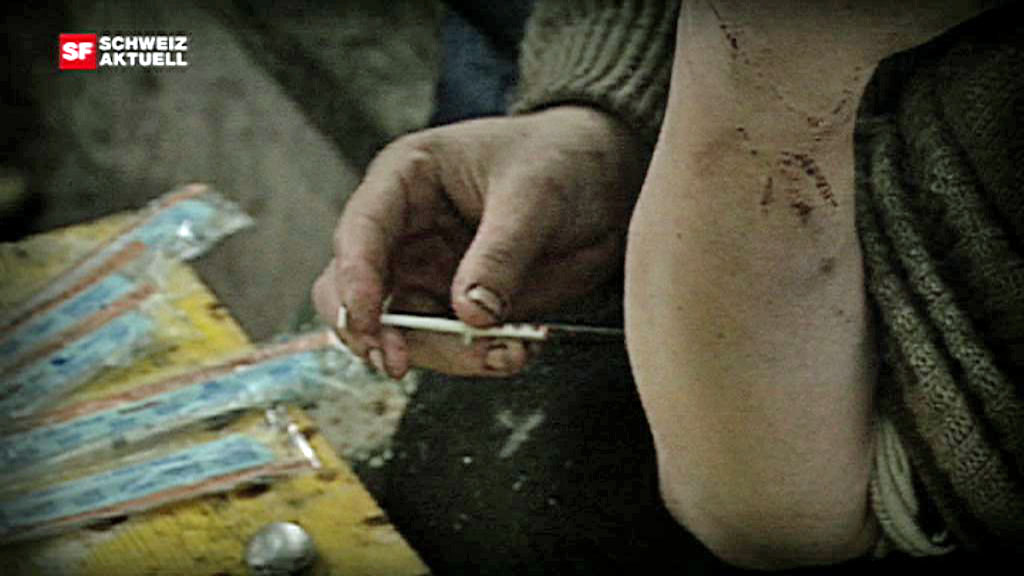

He said the same method, using a different sensor, could also be used for heroin tests.

Legal status

Under Swiss law, forensic medical tests are the only ones accepted as legal proof to sanction illegal drug use behind the wheel.

“There are no exceptions. If this kind of sensor were to be accepted by the courts, it would necessitate a change in the law,” said Frank Rüfenacht, head of the transport division at Bern’s cantonal police.

Swiss police currently use two kinds of preliminary drug tests: saliva or urine, which can give positive or negative results for four substances: cocaine, heroin, marijuana and amphetamines. The second stage is to take the suspect to hospital to carry out a quantitative blood test, the only one recognised by the justice system.

Rüfenacht, described the current indicative urine test, which costs SFr25, as “effective and reliable”. Before that it was impossible to realise a preliminary analysis on the spot.

“The ideal thing would be a reliable device that measures saliva and can convert amounts into precise concentrations of different illegal substances in the blood,” said Antonello Laveglia, spokesman for the Federal Roads Office.

He added that pushing through changes in the law would not be that straightforward, however.

“Just look at the problems created by our proposal to admit preliminary breath tests as proof of drunkenness behind the wheel,” he said, referring to efforts to include the idea in planned changes to road safety legislation, “Via Sicura”.

Road accidents

Franziska Eckmann, director of Infodrog, the coordination office of addiction facilities, was positive about the new research: “It makes sense to look for a simpler, cheaper solution such as this new device,” she said.

She cited a recent study that found that six out of ten drivers suspected of being under the influence of psychotropic drugs when involved in traffic accidents gave positive blood tests.

The tests were requested by seven cantonal police forces to the Forensic Institute in Zurich between 2006 and 2010.

Although this was only a regional study, it reflected a certain reality.

Half of all positive tests were for alcohol and the other half for the use of various illegal drugs – often more than one – generally mixed with alcohol: 73 per cent cannabis, 38 per cent cocaine, ten per cent morphine, four per cent amphetamines, five per cent ecstasy and eight per cent methadone.

In Switzerland it is assumed that five per cent of serious road accidents are caused by people using illegal drugs or medicines.

“In the case of alcohol, it’s 15 per cent,” Magali Dubois, spokeswoman for the Swiss Council for Accident Prevention. “The risk of accidents is up to 14 times higher when alcohol is mixed with other drugs, even in small amounts.

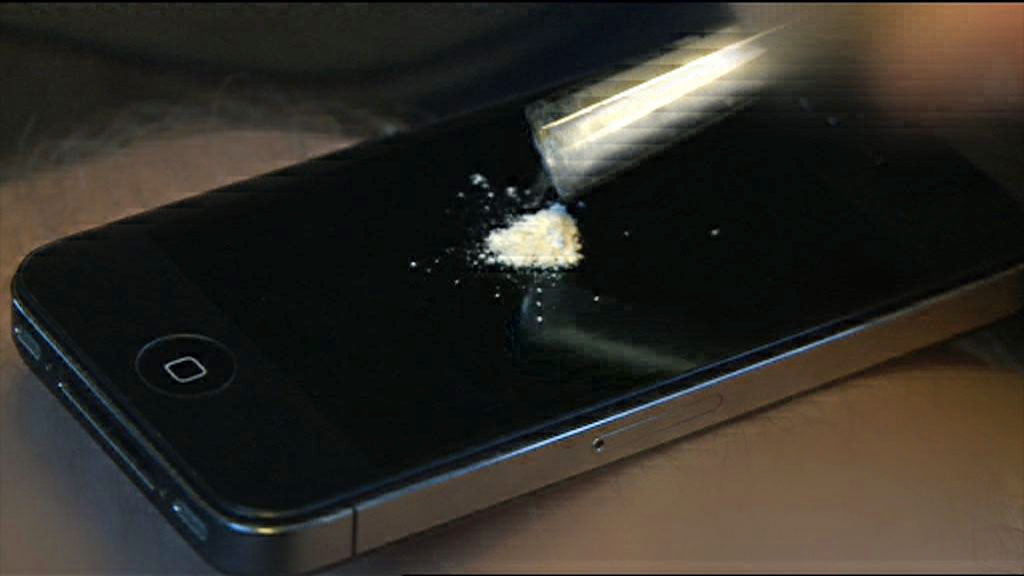

The consumption of cocaine in Switzerland has increased exponentially over the past five years. Between 25,000 and 60,000 Swiss are estimated to take cocaine every day.

Supply struggles to keep up with demand. Dealers are increasingly mixing cocaine with other substances, such as sugar or other pharmaceutical products, and what people buy can sometimes only be 20% cocaine, according to cantonal police officers.

The cocaine is produced in Latin America and arrives in Europe via West Africa.

Dealers on the streets of Zurich, Bern, Geneva or Lugano are generally African; their customers are generally Swiss.

A 2010 study found that illegal drugs were more common among younger drivers.

Older offenders were more likely to be under the influence of prescription medication (eight per cent), which is not forbidden outright in Switzerland. But even in these cases the study found that drivers had often taken legal medication with alcohol, marijuana or opiates.

The biggest group of offenders were in their 20s. 89 per cent were male. The youngest was 14; the oldest was 92. The average age of the drivers was 31.

About a third of the samples were taken after an accident.

(Adapted from Spanish by Simon Bradley)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.