Swiss to vote on funding of abortion

Abortion is back on the political agenda in Switzerland. A new initiative proposes that voluntary termination of pregnancy no longer be reimbursed by compulsory health insurance. A nationwide vote takes place on February 9.

The strength of the people’s response in June 2002 seemed to have put an end to decades of bitter debates on abortion in Switzerland. With over 72% of votes cast, the electorate had approved what was known as the first-trimester solution, which meant the decriminalisation of abortion in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. At the same time, 82% rejected an initiative that would have prohibited most terminations of pregnancy.

The anti-abortion forces have now returned to the charge, opening up a new debate on the funding of voluntary termination of pregnancy. When an initial attempt through a parlamentary motion to exclude abortion and foetal reduction from the items covered by compulsory health insurance failed in 2009, campaigners decided to go the route of direct democracy.

Their initiative, called “funding of abortion is a private matter”, was signed by about 110,000 eligible voters and is therefore to be submitted to a popular vote. In parliament it got the support of just a few Christian Democrats, a member of the Protestant Party and a bare majority of the Swiss People’s Party.

Launched by an inter-party committee made up essentially of conservative Christians, the initiative “funding of abortion is a private matter ˗ relieving the burden on health insurance by removing the costs of termination of pregnancy from basic health insurance” calls for the introduction of a new article in the federal constitution. It states:

“With rare exceptions concerning the mother, termination of pregnancy and foetal reduction are not included in compulsory health insurance”.

Like every constitutional change, the initiative will require a majority both of the nation’s people and of the cantons to pass.

Drop in abortions

Under this proposal, “abortion would remain legal, but paying for it would be a private responsibility”, explains Elvira Bader, a former Christian Democrat parliamentarian and co-chair of the “yes” committee, composed of conservative Christians.

For opponents of the proposal, this is just a pretext to block access to abortion. “The promoters of the initiative are trying to fight abortion with different means, attacking the principle of solidarity, which is the cornerstone of compulsory health insurance,” claims Christian Democrat parliamentarian Lucrezia Meier-Schatz.

“I too, like my party, would like to have seen a different solution from the first-trimester rule. But this is the solution chosen by a definite majority of the people and so I respect it,” she says. “All the more because the present situation gives no cause for alarm.”

Since the introduction of the first-trimester rule, the number of abortions in Switzerland fell and then remained stable at around 11,000 a year. In the years preceding the change to the Criminal Code it had been more than 12,000.

Misunderstanding?

Advocates of the initiative claim that in the 2002 vote many citizens did not understand what was at stake concerning compulsory health insurance.

Changes to the covering of costs by the insurance fund were submitted for the people’s approval together with changes to the Criminal Code regarding abortion. It was all on the ballot paper. Indeed, the opponents argued that “it is just scandalous that even if someone is opposed to abortion they should be forced to pay for it with ever-increasing health insurance premiums”.

Bader claims that “we found when gathering signatures for this initiative that many people had not realised that [by accepting the first-trimester rule in 2002] they were also deciding to pay for abortions through their compulsory insurance”.

According to government figures, the cost of a termination of pregnancy ranges from CHF600-3,000 ($670-3,350). The average cost of a pharmacological termination is CHF650 and a surgical termination comes to CHF1,000.

Overall, the costs are estimated at about CHF8 million a year. If treatment following an abortion is included, they are CHF10-12 million. This represents about 0.05% of all the costs that are covered by compulsory health insurance. However, a part of the cost is assumed directly by the pregnant women (deductible and percentage of costs to be paid) and is thus not incurred by the health insurance fund.

It is thought that these costs correspond to an average charge of CHF0.05-0.06 a month per insured person, as health minister Alain Berset told parliament.

A matter of ethics

Being forced to pay for abortion troubles the conscience of people opposed to the practice, according to advocates of the new initiative.

Furthermore, says Bader, putting the emphasis on ethical and moral considerations, it is contrary to the very principles of the legislation, the aim of which is “to promote health, heal suffering or alleviate it, and above all protect human life, not destroy it”.

“From the ethical point of view, women’s health should be put at the centre of this debate. In fact, this initiative makes it into a debate about money, not conscience,” counters Meier-Schatz.

She believes privatisation of the costs of abortion would take the country back to the situation before 2002, with varying applications of the law and unequal treatment. The minority of well-to-do women who have ready access to termination of pregnancy would continue to do so, while many women in marginal situations would have to look for solutions outside the legal framework.

Bader counters: “Private insurance premiums are not so high that people could not afford them. And an abortion today is not all that expensive: it does not reduce someone to beggary. In Austria abortions have been a private responsibility for the past 40 years, but there has been no increase in illegal abortions or risks of impoverishment.”

On the other hand, “studies carried out in the US show that when abortion is funded privately, sexuality is handled with greater awareness and individual responsibility”.

Back-street abortions

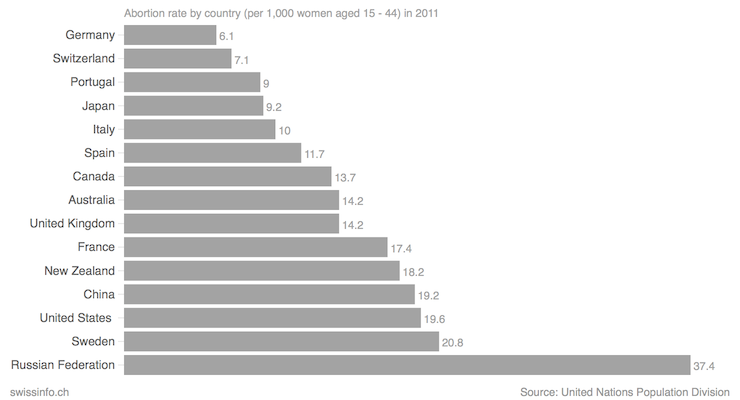

Opponents of the initiative point out that the rate of abortions among women of fertile age in Switzerland is much lower than in the US – 7.1 per thousand women as opposed to 19.6 per thousand, according to UN data for 2011 – and it is one of the lowest in the world.

In Switzerland, in particular, the rate of abortion among 15- to 19-year-olds decreased from 6 to 4.5 per thousand between 2005 and 2012.

It is precisely these young women who cannot count on the support of their own families, who are without insurance coverage and who lack the financial means necessary to pay for a termination of pregnancy who would be most likely to abort outside the legal framework.

“We would go back to the days of back-street abortion,” warns Meier-Schatz.

This would in turn drive up the costs incurred by compulsory health insurance. In other words, it would have the contrary effect to one of the main goals stated by advocates of the initiative: to reduce the costs incurred by the health insurance fund. This is because “treatment for the after-effects of terminations of pregnancy not carried out under proper conditions would be reimbursable”, Meier-Schatz emphasises.

Foetal reduction, or selective reduction, means the elimination of one or more embryos in a multiple pregnancy. This is generally done to reduce risks, especially those linked to premature births, and to improve the prognosis for the remaining embryos.

In Switzerland foetal reduction is currently governed by the same legislative provisions as termination of pregnancy, the Federal Health Office told swissinfo.ch.

To be precise, under article 119 of the Criminal Code, termination of pregnancy is not an offence if “the termination is, in the judgment of a physician, necessary in order to be able to prevent the pregnant woman from sustaining serious physical injury or serious psychological distress” or if “at the written request of a pregnant woman, who claims that she is in a state of distress, it is performed within 12 weeks of the start of the pregnant woman’s last period by a physician who is licensed to practise his profession”. These costs are covered by compulsory health insurance.

“From a judicial point of view it is irrelevant whether the pregnancy was induced in a natural way or through in vitro (IV) fertilisation,” notes the Federal Health Office. It also points out that in an IV fertilisation only three ovocytes per cycle may be developed into embryos.

(Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.