Ten years on from Needle Park

In the ten years since the world's most infamous haunt for addicts closed in Zurich, Swiss drugs policy has come a long way.

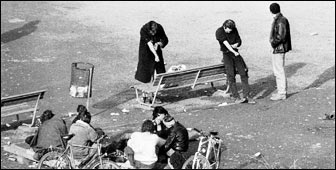

The Platzspitz, which had become known as “Needle Park”, attracted hundreds of heroin addicts daily. In the park, users from all over Europe bought their drugs, and injected them openly.

Some social workers and doctors treating drug addicts believed the Platzspitz had its advantages – at least addicts were in one specific place where they could be given clean needles and help quickly if they overdosed.

But bitter complaints from local residents, and concern among Zurich politicians about the city’s image led to the park’s closure. On February 4, 1992, Zurich police move into the Platzspitz and cleared away the addicts.

From then on, although some drugs users did try to gather in Zurich’s Letten area, the open drugs scene was over.

Harm reduction

A direct consequence of the closure of the Platzspitz was the introduction first in Zurich and then right across Switzerland of a series of harm reduction measures for drug addicts.

The measures supplemented Switzerland’s existing policies of repression, education and treatment for drug abuse.

Needle exchanges were set up, where addicts could swap used needles for clean ones. Injection rooms were opened where heroin users could inject their drug away from the streets, and under the supervision of trained medical staff.

Dr Daniel Meili, a leading member of the association for the reduction in the risks of drug abuse, says the past ten years have brought great improvements.

“Things have really got much better,” he told swissinfo. “We have lots of injection rooms, we have a big methadone programme, and we can even prescribe heroin too.”

Prescribing heroin

Meili is also chief medical officer for Zurich’s programme of heroin prescription. When the programme was first introduced in 1994, it was very controversial, but after studies indicated that addicts on the programme had achieved a better state of health and a more stable life style, other regions of Switzerland introduced heroin prescription too.

Over the past ten years, drug related deaths in Switzerland have fallen, as have levels of HIV infection.

Convinced by the results, Swiss voters decided in 1997 to support continued government funding of the programme. There are now heroin prescription programmes in all of Switzerland’s cities, and in most major towns.

Although other countries such as Holland and Australia have expressed interest in Swiss drugs policy, prescribing illegal narcotics remains very controversial, and Switzerland remains the only country in the world to operate a widespread, government funded programme of heroin prescription.

Getting addicts off drugs

However, some critics say Switzerland’s drugs policy has got out of hand, and that the overall goal – of getting addicts off drugs – has been forgotten.

Walter Häcki, a Swiss People’s Party representative in Lucerne’s cantonal parliament, wants the heroin prescription programme stopped.

“The Swiss government’s policy simply maintains people on drugs,“ Häcki told swissinfo. “What we should be doing is getting them into abstinence programmes, so that in the end they can get off the drugs, and have happy fulfilled lives. Drug addicts have a right to that too.”

Häcki might be surprised to discover that his views are shared at least in part by Robert Reithauer, the social worker in charge of the injection and smokers’ room in Zurich. Where they differ, is over the method of achieving abstinence.

“Of course it’s always better if someone can live their life without being dependent on drugs,“ said Reithauer. “And I’m sure that our programme of harm reduction helps people to find new ways of living.

“We won’t see progress with the people here overnight, but over months or years we will. At some point some of the people here will ask me for help to come off drugs.“

When Reithauer opens the door of the centre each morning, there is a long queue of drug addicts impatiently waiting. Reithauer greets them; he knows most by name.

“If I didn’t have the hope that some of these people would be able to achieve normal drug free lives in the future,“ he said, “I wouldn’t work here anymore.“

by Imogen Foulkes

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.