The Gurlitt art collection no one – and everyone – wants

No other event since the Second World War has raised awareness of Nazi-looted art more than the discovery in February 2012 of a hoard of 1,240 artworks presumed destroyed in the bombings of the last war. All eyes are now on the Swiss museum that’s inherited it.

Bern’s Museum of Fine Arts had planned to announce on November 26 whether it will accept the collection. It has now said the announcement will happen two days earlier – and in Berlin. The development supports the rumour that the museum will accept the collection, but leave it in Germany to allow for provenance research to be completed and potential claims to be addressed.

The collection was gathered by Hildebrand Gurlitt, an art merchant who acted for the Nazis, and squirrelled away in a Munich apartment owned by his reclusive son, Cornelius Gurlitt, who died earlier this year with no direct descendants.

In a snub to the German authorities that seized his collection when it was accidentally discovered during a police raid on his home for tax reasons, Cornelius designated the Swiss museum his sole heir. Gurlitt operated in full legality because the German statute of limitations of 30 years put his collection beyond the reach of claimants. Or, so he thought.

The exact number of art works found in Gurlitt’s homes in Germany and subsequently in Austria has never been officially confirmed and varies between 1,240 and 1,650 pieces. Nor has there been any information on the empty frames that may have held paintings quietly sold over the years by Gurlitt and his family with the silent complicity of the art market.

More

Inside the Gurlitt collection

A legal imbroglio

If the museum accepts the bequest, it will be bound by the Washington Principles on Nazi-confiscated ArtExternal link, a code of ethics signed by 44 countries in 1998, including Switzerland, that calls for the active restitution of Nazi-looted art. In 2009, an additional two countries joined.

According to a recently published report by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against GermanyExternal link and the World Jewish Restitution OrganizationExternal link two-thirds of the nations have made little or no progress to identify and return artwork bought or confiscated from Jews during the 1930s and 1940s.

There is now hope that the high-profile Gurlitt case will establish restitution procedures that even the most resistant countries, like Italy, Russia, Poland, Spain, Hungary and Argentina will feel obliged to follow.

More

‘There’s a lot of Nazi-looted art in Switzerland’

In the meantime, the Bern museum’s board of trustees is reviewing the legal ramifications of a gift that could potentially unleash claims from the heirs of Jewish families that fled to countries where the laws are different to those in Germany.

The Museum of Fine Arts must also weigh the moral implications of accepting a collection in which already one third of the content has been identified as confiscated from its rightful owners. The list was posted online on the German Lost Art database under Munich TroveExternal link (also known as the Schwabing Trove, a suburb of Munich where Gurlitt lived).

There is however very little known of the remaining two-thirds of the collection. German authorities, who held the 2012 discovery secret for two years, are being accused of obfuscation and obstruction by an armada of potential claimants, many of whom have reached old age and are naturally impatient. The Schwabing Art Trove Task Force was finally established in January 2014 but has yet to deliver progress reports on its findings.

Negotiating a deal with Germany

US litigation lawyer, Nicholas O’Donnell, who specialises in wartime restitution claims and produces Art Law ReportExternal link, has been following the case closely. He believes that the Bern museum will accept the gift, but would likely request some kind of indemnification from Germany to face either the expense of receiving the collection, or restitution costs.

“Germany must be considering the possibility just to get rid of the problem,” he told swissinfo.ch.

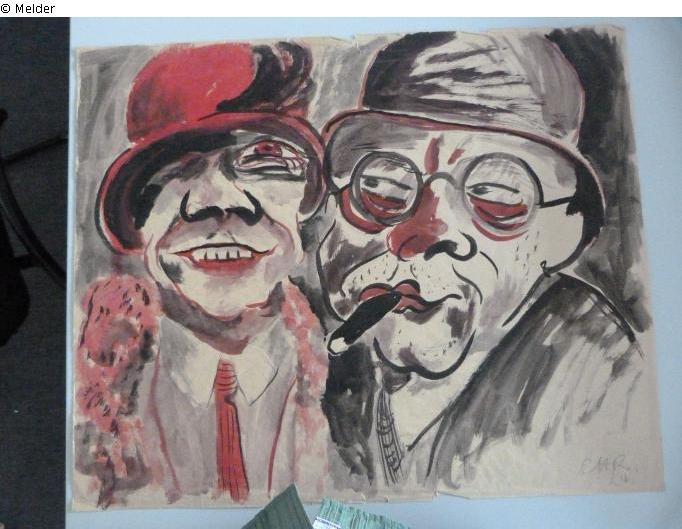

The Nazis in effect turned an entire category of modern art that they qualified as degenerate into “contraband”, which further complicates tracing its movements during and after the war. And incidentally, not all owners of the confiscated “degenerate art” were Jewish, O’Donnell reminds us.

Asked whether the Bern museum, as a private foundation, would eventually be free to sell works of the collection to cover its costs, O’Donnell answered: “Nobody is going to buy art with inconclusive provenance.”

“Until the mid 90s, a work labelled ‘From a private collection, Paris, 1942’ would not have raised any eyebrows, but since the Washington Principles, it stands out as a red flag,” he said.

It is his belief that Bern and Germany are currently negotiating on a number of contingencies to finalise a deal before November 24. “It’s about time things got moving,” he said.

An elegant solution

Like many other museum professionals, Bernhard Fibicher, director of the Fine Arts Museum in Lausanne, originally thought that he would refuse for ethical reasons to go anywhere near a tainted collection, but he has changed his mind.

Fibicher indicated that if Bern refused the bequest, the works of art could become entangled in endless probate procedures, that could well end up identifying Gurlitt’s distant relatives as the rightful heirs, at least to part of the collection.

Members of the Gurlitt family, some who are Jewish themselves, have since pledged that they would return any looted art to their rightful owners if the Bern museum were to refuse the collection. What would happen to the unclaimed art has not been specified.

According to Fibicher, the Bern museum should accept the bequest and leave it in Germany until all the provenance issues are resolved. “That would be an elegant solution,” he said.

Furthermore, by accepting the gift, the museum would be respecting the terms of the will, creating precedence for the strict adherence to the Washington Principles that other museums would have to follow. And, just as importantly, it would be allowing the task force to complete the research for which it is equipped in a way that Bern is not.

There is however a danger that makes him uncomfortable, that the collection become a travelling road show lent to other museums that would draw crowds for box office purposes.

Ironically, the quality of the Gurlitt collection is said to have been greatly exaggerated. And the few ‘masterpieces’ that it contains will probably be the first to be successfully reclaimed.

An opportunity for Switzerland

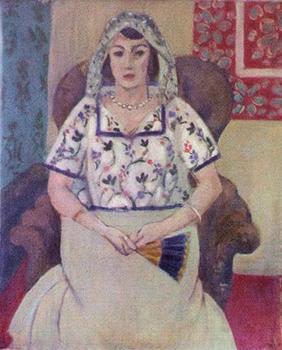

One such piece is the Matisse painting, considered to be one of the finest of the collection. Counsel to the Rosenberg heirs, the founder and director of Art Recovery InternationalExternal link, Christopher Marinello and his team immediately set the wheels in motion to recover the painting when its existence became known.

He joins the chorus of criticism against the “insensitive” task force, but praises the individual provenance researchers. In his opinion, they are excellent, but overwhelmed.

“You can put together the best football team in the world, but without appropriate coaching and management support, it’s going to be difficult to win a match.”

Provenance research, Matthias Henkel of the German task force reminded swissinfo.ch during an initial exchange, is tremendously difficult and takes more time than anyone can imagine. It is now fairly certain that the one-year deadline to clarify the Gurlitt estate will not be met.

According to Marinello, the Gurlitt bequest is a great opportunity for a Swiss institution to take the lead and make up for Germany’s deficiencies in this case.

“I would urge the Museum of Fine Arts to accept the Gurlitt bequest and resolve the issues over the Nazi-looted works of art in accordance with the Washington Principles,” he stated.

Breaking the silence and secrecy

Marinello’s view is shared by Anne Webber, co-founder of the Commission for Looted Art in Europe (CLAE) that publishes a comprehensive websiteExternal link dedicated to Nazi looted art news stories and leads. A former filmmaker, she is recognised as a formidable restitution advocate.

“With ownership, comes responsibility. If Bern accepts the Gurlitt collection, then it is essential that all research continue with greater transparency,” she said.

Webber is known for her forthright positions and points out that while Germany has been exemplary in dealing with its Nazi legacy, art remains its “Achilles heel”. She sees the possible bequest to Bern as an opportunity to break the silence and secrecy that is maintained in Germany.

“The identities of the actual provenance researchers on the German task force have not been disclosed. It’s unclear why this hasn’t happened. Transparency is essential if people are to have confidence in the work of the task force,” she said.

She pointed out that Switzerland has failed to live up to its commitment to do provenance research in all its public collections on works that have been acquired since 1933 and believes that the Gurlitt bequest could provide the trigger to implementing that commitment.

Filling the empty frames

Webber then explained that the investigation must be broader than the works found in Gurlitt’s possession. “The art that was sold out of the collection from his father’s time onwards must also be traced and identified”.

Cornelius Gurlitt, who had no declared source of income, is known to have sold several works of art, as did his mother and sister after the death of Hildebrand in a car crash in 1956.

Webber quotes Alfred Weidinger, deputy director of the stately Belvedere Museum in Austria: “The fact that this collection existed was not a secret. Every major art dealer in Southern Germany knew – and knew how extensive it was.” She added that dealers in Austria and Switzerland also sold works on behalf of the Gurlitt family.

How the art market remained a secret accomplice to the Gurlitt clan has yet to be clarified. “We are calling for a full investigation and are inviting dealers who disposed of the works, including to museums, to come forward,” Webber explained.

She repeated how the transfer to Switzerland of the collection “could set a model for provenance research and draw up a template for fair and just solutions”.

“The Museum of Fine Arts could help provide the transparency that wronged families so desperately need,” she said.

The task force

A task forceExternal link was established by the German federal government and the government of the Free State of Bavaria in January 2014 but with an ambiguous mandate because it is to conduct provenance research, but also assist the public prosecutor’s office and German courts “with the necessary research, clarifying the origin and circumstances … of the artworks found in Mr Gurlitt’s home”. It has made only two restitution recommendations to date, including one, ‘Two Riders on the Beach’ by Max LiebermannExternal link, which, in a surprise development, is being opposed by the German state itself and ‘Woman With a Fan’ by Henri Matisse, that is currently being negotiated with the descendants of art merchant Paul Rosenberg, including the high-profile French journalist, Anne Sinclair.

swissinfo.ch approached the Schwabing Art Trove Task Force to obtain the following clarifications: did its mandate extend to searching and identifying possible owners and would it continue to operate regardless of Bern’s decision? The question of the task force’s legal protection from the “avalanche” of lawsuits promised Bern by former leader of the World Jewish Congress, Ronald Lauder, if it accepts the collection, was also raised. “Sorry to say – but at the moment, [task force head] Dr. Berggreen-Merkel is unwilling to answer your questions,” was the written reply.

Nazi-looted art databases

Provenance research is highly reliant on the constitution and aggregation of databases. Washington-based International Research Portal for Records Related to Nazi-Era Cultural PropertyExternal link, created in 2011, aims to become the super-aggregator of all information from all available portals, including:

Looted Art central registryExternal link open to all.

Art Claim at Art Recovery InternationalExternal link that also proposes high tech visual recognition of art works.

German Lost Art databaseExternal link where the Gurlitt collection is being posted piecemeal.

And all national looted art databases, including from SwitzerlandExternal link.

Testing the water for a re-evaluation

Uta Werner, a cousin of Cornelius Gurlitt, has obtained an expert opinion from a psychiatrist that the art collector was delusional and not of sound mind, when close to the end of his life he made the Bern Museum of Fine Arts the sole heir to his will.

The legal practitioner and psychiatrist Halmut Hausner had never met Gurlitt, but based his opinion that he was suffering from a “Schizoid Personality Disorder” on documents and conversations with people who knew him. The cousin’s lawyer, Wolfgang Seybold said they were not officially challenging the will at the moment, but have not ruled this out completely. The will’s validity is therefore not currently being checked as a request to contest the will has not been lodged.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.