Perfect storm closes in on luxury goods sector

When pro-democracy demonstrators took to the streets of Hong Kong in September, the luxury industry was challenged by another tumultuous event in a year it would rather forget.

The Chinese government’s 18-month-old clampdown on lavish gift-giving by officials in mainland China was already taking its toll. Then in March, the outlook for the industry was mired in further uncertainty, provoked by Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the problems in Ukraine, which resulted in political fallout with Europe and the US.

The situation in Hong Kong – a third unforeseen calamity, this time taking place in the world’s biggest market for Swiss watches – provoked Luca Solca, a luxury analyst at Exane BNP Paribas, to declare this month: “There seems to be a perfect storm closing in on the luxury goods sector.”

The unrest in Hong Kong is particularly worrying. The territory accounts for about 20 per cent of global sales of Swiss watches, according to Jon Cox, an analyst at Kepler Cheuvreux.

More

Financial Times

External linkHong Kong’s rise is largely the result of its status as the go-to shopping destination for mainland Chinese, who take advantage of lower consumption taxes. But its importance has also been magnified by the relative lack of dynamism in leading European markets.

Indeed, a report this month by Bain & Company and Fondazione Altagamma concluded that Chinese consumers are now the most important market for personal luxury products, accounting for a whopping 29 per cent of the global total.

By contrast, Americans account for 22 per cent and Europeans just 21 per cent.

Against that backdrop, and a day after the first protests broke out in Hong Kong, Mr Cox of Kepler Cheuvreux cut his 2014 growth forecast for the Swiss watch market from 5.5 per cent to just 3.5 per cent – about half the annual average over the past 30 years or more.

Barely a week after the Hong Kong protests began, Tag Heuer announced that it would cut 46 jobs in management and production.

Jean-Claude Biver, who heads the watches division at LVMH group, which owns Tag Heuer, said in September that the industry had grown just 2.7 per cent in the year to August – considerably less than his earlier prediction of between 4 and 6 per cent. A few days earlier, Cartier, which is owned by Compagnie Financiere Richemont, confirmed it was implementing a reduced working week for 230 of its employees in Switzerland.

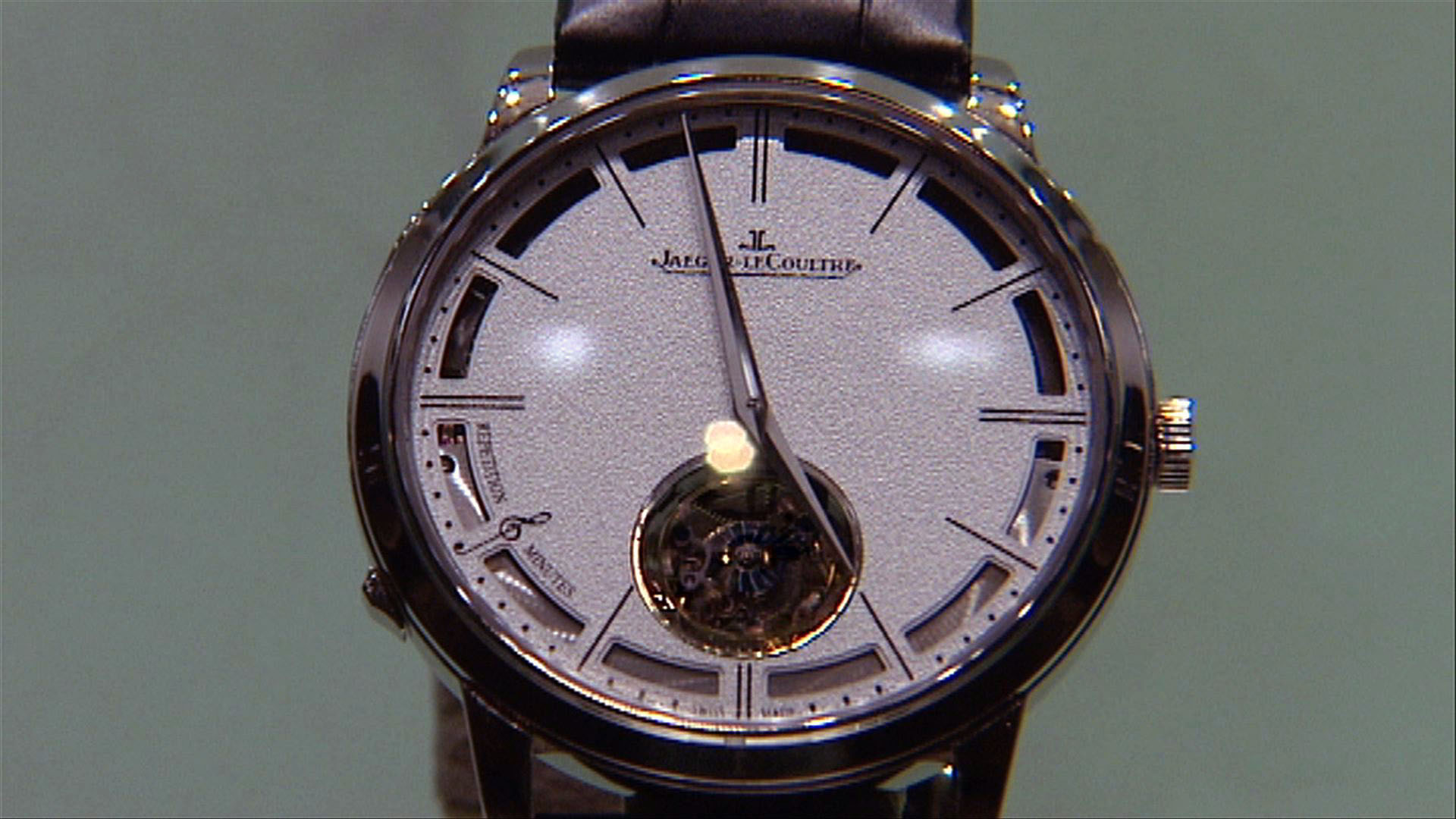

Shares in Switzerland-based Richemont, whose brands include Jaeger-LeCoultre and Vacheron Constantin, have fallen 11.9 per cent so far this year, reflecting the more complicated global trading environment.

Swatch Group, the world’s biggest maker of Swiss watches with about 21 per cent of the market, has declined nearly 25 per cent so far this year.

Even the more diversified LVMH, the world’s largest luxury group controlled by French billionaire Bernard Arnault, is slightly down since January.

So how bad are things going to get? After all, Hong Kong represents some 17 per cent of sales in the case of Richemont; for Swatch Group, it is an estimated 15 per cent of group revenue.

Mr Cox of Kepler Cheuvreux contrasts the structures of the Swiss watch and the fine jewellery markets.

The fine jewellery market is worth about €150 billion (CHF180 billion) a year. But only about 20 per cent of that is branded, with the rest fragmented among hundreds – perhaps thousands – of companies selling their products through independent stores.

The result, says Mr Cox, is an industry that has proved far more resilient to the clampdown on luxury gift-giving in China, with overall growth this year expected to reach the high single digits.

He also thinks that bigger groups will continue to win market share over time. “The bigger players have deeper pockets and bigger balance sheets,” he says. “That matters in an industry where global distribution and marketing are increasingly important.”

The fine watches industry, by contrast, is already highly consolidated. Swatch Group, Richemont, Rolex and LVMH, the four biggest groups, together account for almost two-thirds of the CHF21 billion-a-year Swiss watch market.

With considerably more high-profile branding than the jewellery market, it is no surprise that the Swiss watch industry has suffered much more at the hands of the Chinese government’s clampdown.

“Concerns about falling prey to anti-corruption efforts seem to have become widespread among wealthy Chinese,” says Mr Solca of Exane BNP Paribas.

Mr Cox puts it more bluntly. “The mainland’s well-documented clampdown on public-sector gifting has knocked the stuffing out of the mainland Chinese watch market.”

But the crackdown has also coincided with a macroeconomic change of pace, with the world’s second-largest economy moving from double-digit rates of growth to an expected 7 per cent this year and beyond.

Mr Solca believes the big luxury brands have suffered a triple-whammy effect. First, many wealthy Chinese customers have become more sophisticated and moved on to smaller, niche brands. Second, he says, the Chinese have cut gift-giving and reined in their personal spending. Finally, the big brands are not capturing aspirational consumers, because these people are turning to brands at lower price points.

The result is, he says, that Chinese consumers tend to concentrate on what is new, then move on, often with alarming speed, to the next brand.

In spite of obvious short-term difficulties, most analysts remain optimistic about the medium-term prospects for watches and jewellery – not least because the numbers of rich people are still increasing. According to the annual Capgemini World Wealth Report, the number of high-net-worth individuals – defined as people who have at least $1 million (CHF960,000) of investable assets, excluding their primary residence – increased by 2 million in 2013 to 14 million. In Asia, the number expanded 17.3 per cent last year, and is now level pegging with North America.

There is even some initial evidence that the fall in Chinese sales may be bottoming out. According to the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry, export growth to China, which fell last year, started to recover in July 2014.

Moreover, the total wealth of high-net-worth individuals grew 14 per cent last year, reaching $52.6 trillion. During that time, the Swiss watch industry exported just 1.6 million high-end watches, which have a retail value starting at $17,000.

Untapped demand, in a market in which the leading manufacturers do not compete on price, is likely to mean a fairly rapid reversion to the industry’s mean growth rates when the present troubles have abated.

As Mr Cox says: “Overall, we remain fully convinced about the business model of the listed watchmakers.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2014

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.