Why small ponds have enormous value

Ponds may not seem as glamorous as rushing rivers or majestic lakes, but they’re indispensable when it comes to biodiversity and ecosystem health. In Switzerland natural ponds have all but vanished with the rise of agricultural intensification.

Only 12 kilometres to the east of the bustling city of Geneva at the Lullier Horticultural School, a cattail-shrouded pond blends in so perfectly with the bucolic surroundings that the eye passes right over it. But as Beat Oertli, a professor of aquatic ecology at the University of Applied Sciences of Western Switzerland (HESSO) explains, this pond isn’t just part of the landscape: it’s been strategically placed to protect a natural stream that lies downhill from one of the school’s fruit orchards.

“This is not a nice-looking pond, but its function isn’t to look nice,” Oertli says. “We’ve constructed it to protect the stream, because here at our school we use some fertilisers. All the rainwater flows into the pond first, where it is naturally filtered. Research shows that ponds like this can trap and degrade about 70% of pesticides that enter it within a year.”

More

The pond shortage threatening biodiversity

It turns out that water purification and filtration is just one item on a very long list of services that ponds provide, both for humans and the environment. These services range from flood and erosion prevention, to habitat for endangered species – even absorption of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide.

“We’ve estimated that one pond can trap as much carbon as one car produces in a year,” Oertli says.

But he explains that these services are in danger of disappearing: over the last 200 years, 90% of ponds and small pools in Switzerland have dried up or been destroyed, largely as a direct result of human activities and agricultural intensification.

Vital networks

It’s easy to underestimate the environmental contribution of ponds, given their small size compared to larger freshwater resources like lakes and rivers. But as Oertli explains, their greatest ecological benefits are realised on a collective level, as each small body of water plays a key role in a larger network.

“In a region, if you put all the biodiversity of small ponds together, it’s many more species than lakes and rivers. That’s because ponds are all very different – they are like humans: you cannot find two that are the same.”

And it’s not just frogs that love to call Swiss ponds home: they are also crucial habitat for a variety of plants and fish, as well as beavers, shrews, voles, bats, leeches, dragonflies, and pollinators like bees and syrphid fliesExternal link.

But individual ponds are valuable as well, especially in an urban setting, which is the focus of Oertli’s research in Lullier. Even an artificial pond in the middle of a city can host natural biodiversity, as well as provide key services for humans.

“Urbanisation is increasing, and ponds are a good example of systems that provide a lot of services for landscaping, flood protection, education for students and children, for trapping pollutants and purifying waters that flow through the city,” Oertli explains. He adds that urban ponds can even provide a crucial reservoir for irrigating parks and gardens, and even for fighting fires.

Food versus water

According to Oertli, some 32,000 ponds and small water bodies of at least 100 square metres exist in Switzerland today – 100 times the number of lakes. That seems like a lot, but when one considers that the estimated number of ponds at the beginning of the 19th century was over 3 million, it puts the figure into sobering perspective. And it’s not just Switzerland: this downward trend is also observed in other urbanised countries across Europe and in the United States.

Transportation corridors, urbanisation and industrialisation all play a role in dwindling pond numbers, but agriculture is believed to have had the biggest hand in the decline. For one thing, ponds often get filled in or covered over to make room for farm land and facilities. Fertiliser runoff is another factor: excess nutrients contained in fertilisers, like phosphorous, can lead to a phenomenon called eutrophicationExternal link, which causes an unhealthy overgrowth of algae and plants.

And even though ponds are excellent at filtering pesticides, excessive contamination with these chemicals can negatively impact pond ecosystems and make them inhospitable to plants and wildlife.

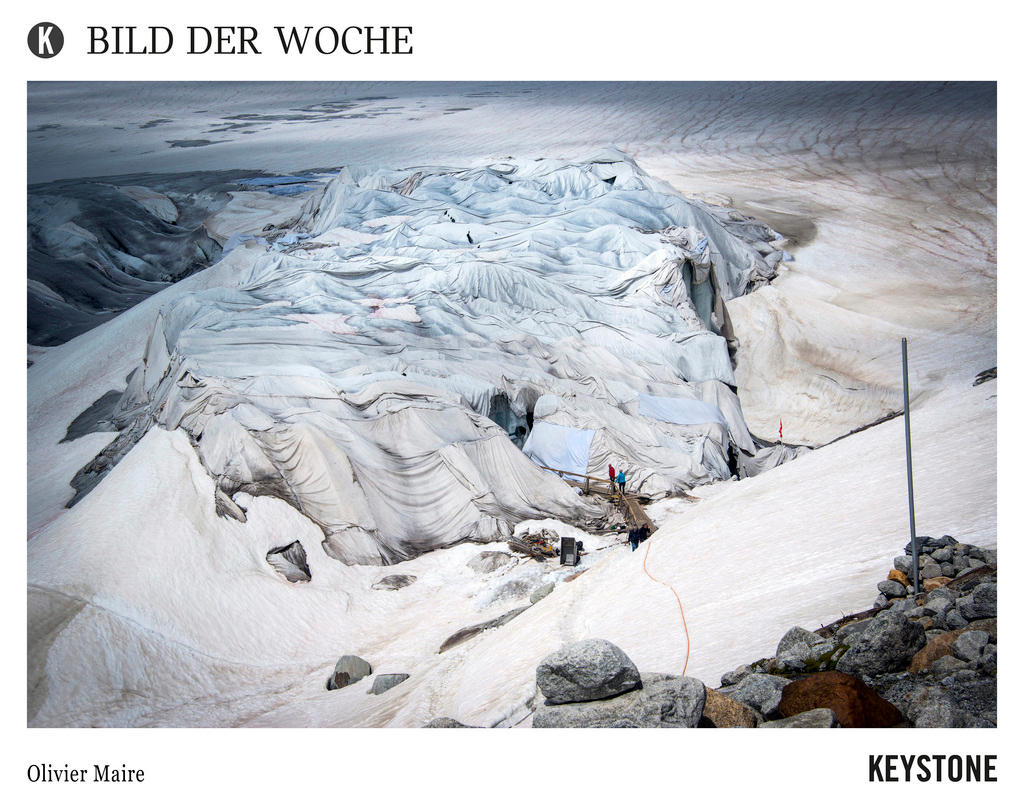

Oertli adds that a changing climate will likely exacerbate these issues. Although every pond will eventually dry up as part of its natural life cycle, climate change can accelerate this process, as pond lifespans tend to be shorter under warmer, more nutrient-rich conditions.

Expert solutions

At a conference held in September by the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (EAWAG), some 300 experts – including Oertli – proposed solutions to the conflict between protecting Switzerland’s water resources and the equally important goal of maintaining a healthy agricultural sector.

According to an EAWAG press release on the event, Eva Reinhard, deputy director of the Federal Office for Agriculture, said at the conference that Swiss agricultural policy from 2022 onward should “bring together consideration of markets, environment and natural resources with those of the agricultural sector”. In her statement, Reinhard emphasised the importance of technology and increased digitalisation in agriculture.

But EAWAG water and agriculture expert Christian Stamm noted that while researchers can help develop models for decision-making and innovative technologies to make agriculture more environmentally friendly, other stakeholders have to contribute to change.

“Science alone cannot bring together the conflicting goals of protection and production,” Stamm said. “Consumers will probably also have to adjust their expectations and demands where food is concerned.”

Oertli also believes that citizens can do their part to improve the pond problem. He argues for a two-pronged approach: protecting Switzerland’s remaining ponds, and constructing new ones. Preserving and creating healthy zones of habitat and vegetation bordering ponds – known as riparian zones – is also key to these efforts.

“In Switzerland, in one square kilometre, there are one or two ponds – this is not enough. We have estimated that the number of ponds in a landscape should be two to three times greater than that to maintain biodiversity. The concept of networks is very important in pond conservation: in Switzerland, some ponds are protected, but I think we have to identify other ponds that are important for a network, and that we need to protect,” he says.

According to Oertli, building artificial ponds is relatively simple and not very expensive – under good conditions, a small pond can be constructed for roughly CHF5,000, he estimates. But even a one-square-metre mini-pond on a private rooftop can be an ecological asset.

“We should have all types of ponds – small and large – so, everyone can do something,” he says.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.